Trektember: The Wrath of Khan | Classics

If it had been the only Star Trek thing ever, we would simply regard Star Trek: The Wrath of Khan as a great movie, like The Adventures of Robin Hood, Seven Samurai, Raiders of the Lost Ark, or The Dark Knight. It can be an entry point for someone who has never seen Star Trek. It introduces its characters well, and while its background lies in a specific episode, the exposition is akin to Obi-Wan’s telling young Luke that he served in the Clone Wars, leaving us no need nor expectation of learning more about those events.

It is grand in a way that science fiction movies weren’t at the time, and still aren’t. I don’t mean big as in action packed, I mean huge, vast and meaningful. The ships are basically battleships. Structurally, Wrath of Khan is a submarine movie, and this is a formula that is very very hard to mess up. Wrath of Khan gets it right and infuses it with heroism, the kind you appreciate most because you believe it. It also has great cat-and-mouse scenes of strategy, and it happens to be a gorgeous movie to look at.

The film is deliberately set in an identifiable reality. While Kirk and Spock talk, the floors are being cleaned; Kirk reads a book (We have e-books now, and people still read books. There will always be books); Communication through quotations (“It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.”) is part of their friendship lexicon, as it is with real friends. It has character based humor because people are funny sometimes. Heroes also fail sometimes, and beat themselves up for it. Trying to be real is a path to honesty, and honesty leads to truths both deliberate and unintended.

The Wrath of Khan is all about costs. Things matter. In a way, everything matters. That’s something I already believe in, so it makes sense that it would appeal to me. It’s the way things are with God, too. He counts the hairs on our heads and the falling of every sparrow. He numbers our days. He decides the when and where of our births, our places in society and so on. He says we will be judged for every idle word. It all matters.

It’s not cheap cost either. Cheap cost is when you watch a TV series with an ongoing plot, and they run the commercial promising that in the next episode, someone! Will! DIE!! That’s death as a drama button, an abstraction that doesn’t hit personally. Star Trek II is certainly not the only decent adventure, or well-acted, filmed, scored and edited movie in the franchise. It works so well because the costs matter. That’s what we really want to see, the times that matter. It’s what we want to hear when we talk to someone after a year or so, “What’s been going on?” We don’t want to know that they went shopping, then hear a list of the items. We do want to know if they were pulling out of a parking space and ran into another car.

This is what stories essentially are. A lot of them miss this, or do it in a merely programmatic way. No, it has to really matter to the characters, to be something they don’t get over immediately, moving on, unaffected, to the next adventure or partner.

Real Costs

This film starts where we might be standing. We open with the Kobayashi Maru scenario, a test designed to determine how a given candidate for command would handle a no-win situation, one ending in losing the battle. Kirk famously cheated on this test as a cadet, but in this run, all of the original series characters on the bridge are killed: Sulu, Uhura, Bones and Spock.  It’s a simulation, unbeknownst to the audience until the viewscreen slides aside and Captain Kirk steps from behind what would have normally been the universe. Nobody has actually died, so we get to start in Kirk’s experience of the Kobayashi Maru; not really having had tested our handling of loss, death, and consequences.

It’s a simulation, unbeknownst to the audience until the viewscreen slides aside and Captain Kirk steps from behind what would have normally been the universe. Nobody has actually died, so we get to start in Kirk’s experience of the Kobayashi Maru; not really having had tested our handling of loss, death, and consequences.

There were no consequences, and this is important. The movie was originally to be called The Undiscovered Country, a Shakespearean reference to death; and a big pointer to the importance of the fact that Kirk has never really confronted it.

His real costs start small. Kirk is an admiral. He looks pretty lackluster; no zest, no verve. He oversees a training simulation, and later does an inspection of a Starship, none of which puts any caffeine in his system. Both Bones and Spock think it was a mistake for him to accept such a promotion. These are comparatively low costs, but they are real; a decision he made some time ago affects every day of his life.

Kirk also must deal with a woman he left, only this isn’t just some green-skinned dancer we saw him kiss. Carol Marcus mattered to him a great deal, and not only because they had a son. We don’t know how they split up, but it is sharply painful for him even to hear her name. Then there’s that son, David, about whom he says, “…my life that could have been, and wasn’t…” It was apparently his choice to not be in his son’s life. That doesn’t prevent him from feeling the loss.

And finally, the Kobayashi Maru scenario is played out, the unwinnable battle, only this time it is not a simulation, and Kirk does not get to rewrite the program to win without cost. The program is rewritten, but as with all real things, it comes with a cost: Spock’s life.

Over all of this is the titular consequence, dealing with the vengeance of a man he exiled on a planet 15 years earlier. The sentence was not only just, but probably merciful. Khan and his people, former brutal conquerors in Earth’s history, had tried to suffocate Kirk and steal the Enterprise to do Roddenberry-only-knows what with the rest of the galaxy. Instead of re-educating, imprisoning or killing them, Kirk gave them an adventure; setting them on a rough, but tameable planet for the supermen they were. But then he didn’t pay any attention to the situation, and a catastrophe changed the weather; it became a mostly unlivable desert planet.

Khan is a great villain because it’s understandable that the things which happened to him would matter. His consequence was turned into something worse than was sentenced, costing lives, even that of his wife, due to Kirk’s negligence. We know he’s the bad guy, but his feeling of being wronged is warranted. Also, his ego has been bruised. He does not have the place in the universe a person of his qualities should have. Ricardo Montalban knew that the villain never thinks he’s the villain, yet I have never heard anyone say anything other than that Khan is a great villain.

That’s quite a weighty load for any film, let alone one with a pedigree. Until recently, in a TV series, at the end of every episode everything had to be back to normal, and so it was with Star Trek. Newcomers and those missing a few installments had to feel as if they could get their footing easily. Movies can be the same way, especially if they’re part of a franchise. Big arc changes are calculated, and in that sense usually predictable; anything else is probably going to get solved. In 1982, we didn’t expect any permanent damage for the main characters and elements of Star Trek, so this movie rolled out the factor of real damage carefully.

That begins when we see Khan stick worms in Chekov’s ear. Our characters had never been so violated in the TV series.

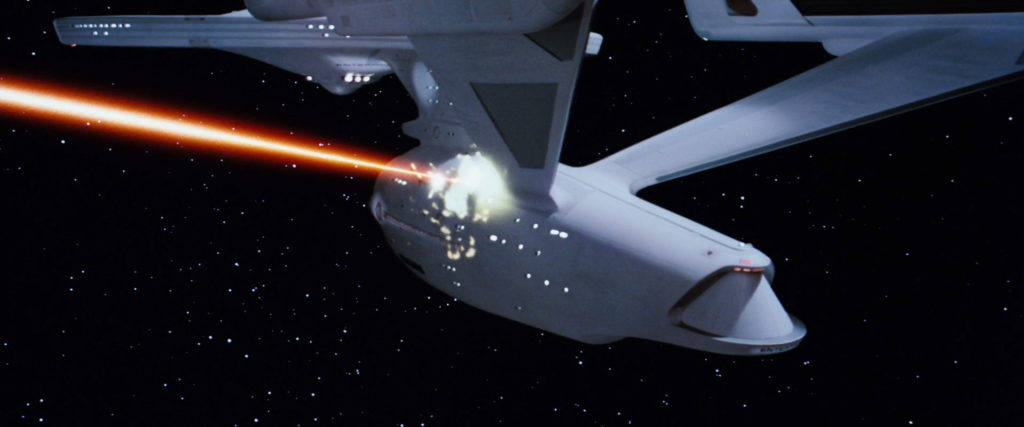

Then the Enterprise gets attacked. It remains one of the most smashing spaceship attacks ever put on film. Even in the age of CGI, battles have never looked more costly on the ships. They either are hit and explode, or they swiftly dodge something. Here, the Enterprise gets carved into.

In an episode of Star Trek, the Enterprise might get hit, some technobabble percentage would go down, there might be some smoke, and the camera might tilt while people jump, but the Enterprise had never been gouged, or dug into. For that matter, neither had the Millennium Falcon. It just wasn’t done.

Then the only new crew member who’s been given lines (aside from Kirstie Alley’s Saavik) is killed. In the director’s cut, he’s Scotty’s nephew; but that isn’t necessary to know. We’ve met him, and we like him, and then he dies, bloody and scorched.

All of this is preparing us to register emotionally, rather than canonically, the death of Spock. Fans often complain about movies by saying, “They changed this, and they never should have done that…” referring to the writers, not the characters. This was a big risk with a Star Trek movie. Killing Spock would have been like killing Luke Skywalker in The Empire Strikes Back; not Han Solo, Luke. But the movie slowly prepared us for a world of Star Trek where costs are incurred, and Spock’s death was considered one of the best moments in cinema for that year (and 1982 was a great year for movies). If you look at lists of best Star Trek scenes, it will always be on them.

I think that in a similar way, our Lord prepares each of us to recognize the cost of his sacrifice to save us. It’s a hard thing to really understand; I used to want to ask theologians, “What did Jesus actually sacrifice? It’s hard to say He sacrificed his life, since He is alive. In fact, He was only dead for a few days. He even knew that He’d be coming back, and about the glories to follow. Resurrection is a spectacular thing, but what did he actually lose?”

Real Loss

Let me zero in on this. At the end of the movie, McCoy says the kind of thing that no one who’s really lost someone ever wants to hear, “You know he’s really not dead, not as long as we remember him.” This is poetic hogwash. The man is dead. He can’t solve your problems anymore. You can’t argue with him anymore. You can’t have a normal conversation with him anymore. He is gone.

When he was alive you could remember him, and that didn’t make him suddenly appear in the room with you. Wondering what he would say wasn’t the same as going to his quarters and asking him, as Kirk does when he needs to change the mission of the ship. He doesn’t wonder what Spock would do, as if that’s good enough. He talks with him because Spock is not a collection of memories; he’s a real person.

And now that he’s dead, Spock is still not a collection of memories, most definitely not a collection of other peoples’ memories. He’s a real person, and that person is no longer accessible to you, Doctor McCoy. His absence matters. Even if time passes, your sadness ebs, and you get used to him not being around, he is still actually gone, and he has suffered loss. Everything he ever was going to be and do, and everything he was ever going to have, has been taken from him. Even if your experience doesn’t validate it, it is real to him.

With Christ, one of his sacrifices was the experience that led to his death. This included being betrayed and abandoned by his closest companions. That’s not a small thing, and He did not have that coming. If you have ever been betrayed by a close friend, even if it was years past, thinking on it probably still hurts.

Another was the physical experience that led to his death. Crucifixion is considered one of the most painful ways for a human being to be forced to expire. He did not have that coming either. In fact, today most of our forward-thinking people would not allow that to be done to their worst enemies. “We don’t torture; we’re better than that.” So even your worst enemy didn’t have that coming. And Jesus went through it to save us.

He also experienced a relational rift with the Father; the first, and only disaffection they would ever have, not because of anything he did. Imagine the person you love most, you trust most, and need most. Imagine that they simply turn their back on you. Ignore you. Walk past you like you don’t exist. Even if it only lasts two or three days, it will be the longest, worst, most deeply painful 2 or 3 days of your life. It will be memorable, scar-worthy, something that goes in your journal, or your memoirs, as an important event.

And it was not something he had coming.

If you take the six Kirk and Spock Star Trek movies as a whole, Kirk really only has to miss his friend for about one movie. Yes, Spock comes back. Ultimately, he’s restored to his full Spock-ness. It forces you to wonder- was the experience of losing Spock, and the time without him, was that costly? Did that time matter? Was that separation relevant?

A criminal goes to prison, and then gets out of prison. The day of release doesn’t nullify the prison term as something that didn’t matter. That experience matters heavily.

Even though Jesus died knowing He would come back, and was separated from the Father knowing He would be restored, He still had to go through it. A separation of this sort, even though it is not fully understood by people, is what Christianity calls the second death, the one that happens after the death of the body, a permanent separation from God and all of his goodness. It is something that people at fault (which is all of us), who do not accept Christ’s sacrifice on their behalf, will have to go through; except for them it will be permanent, and deservedly so.

Jesus experienced that. It was real, it mattered, and it has a weight. The weight of it is colossal. Fortunately, for us.

Spock’s death scene plays with all the significance a death scene should have, even if we know he’s coming back. It’s still an experience. We wonder how God can care about things He knew would, even ordained to, come to pass; how could He not be dispassionate, or even mocking, of our grief? Well, we empathize. We even empathize with fiction! We’re made in His image; our design is based on Him, and whatever we do at all, He does very well. He’s a better empathizer. He is emotionally in touch.

Real Wrath

And, while he’s quite an imperfect match, Khan’s wrath can still help us understand God’s. His anger has justification. He has the ability to carry it out. In the end, he activates the Genesis device, setting up a planet sized explosion from which the damaged Enterprise cannot even limp away. No escape. Judgment is coming, and it will be complete. The proper payment for our violations is death, but our debts are paid by someone else. On the Enterprise, Kirk can do nothing to escape the consequences of having angered Khan. Then, suddenly, he is given the means of escape and he takes it.

He didn’t even notice Spock was gone until his friend had already finished doing what he had to do. And then it was done, having happened without Kirk’s command, without even his permission. He was not consulted or given a choice of rescuers – it was just done for him, his only way out of his calamity, leaving an empty chair. For a while.

Everything we do costs something. Much of it we will never be able to repay; none of it with God, who sees all of it, and knows its depths. We have a rescuer we didn’t choose. If we accept his gift, we are fully rescued. If we would prefer another option, we will not be rescued. To those who simply don’t believe this, don’t believe that Jesus of Nazareth even lived, or if he did, that he was just some kind of a special man, based on his attitudes and teachings, or that he definitely wasn’t God incarnate, or that even if he was, what he did does not take care of my relationship with God – to those who don’t believe those things, all I can suggest is that you seriously look into them, and I do mean seriously, and honestly. Listen to the people who claim they can back up those claims, treat their cases seriously, evaluate them fairly, and see if you can’t be properly convinced, because the results, one way or the other, are substantial.

• • •

Trektember is an annual series about Star Trek; this year, we’re examining the first seasons of Star Trek: Discovery and The Orville. For more information on this series, click here; or, to read every article from the beginning, click here!