The Mere Breath of Winning in Uncut Gems

When director Martin Scorsese finally got a chance to see the first cut of Joshua and Benny Safdie’s 10-years-in-the-making Uncut Gems, he told them, “Don’t change a frame.” Having brought funding to the Safdie’s movie and raising the movie’s profile by being attached, it might seem like paltry input from America’s greatest living director. However, it is more likely the highest of praise from the man who helped define New York cinema in the ’70s and ’80s that he saw a lot of himself in the film. From the close-up camera work to the long-winded, self-important dialogue of ego-driven, flawed main characters, the Safdies channeled much of what Scorsese did in his early films with a mood and style already a hallmark of their own.

When director Martin Scorsese finally got a chance to see the first cut of Joshua and Benny Safdie’s 10-years-in-the-making Uncut Gems, he told them, “Don’t change a frame.” Having brought funding to the Safdie’s movie and raising the movie’s profile by being attached, it might seem like paltry input from America’s greatest living director. However, it is more likely the highest of praise from the man who helped define New York cinema in the ’70s and ’80s that he saw a lot of himself in the film. From the close-up camera work to the long-winded, self-important dialogue of ego-driven, flawed main characters, the Safdies channeled much of what Scorsese did in his early films with a mood and style already a hallmark of their own.

Like all of their previous feature-length films, Uncut Gems take place in the Safdies’ hometown of New York City. Unlike the New York of Raging Bull, Taxi Driver, and Mean Streets that were dark, grimy, sweltering pits of crime and dissension, theirs is a glossy, fast-paced environment of clubs and diamonds. Yet, they are equally the concrete jungle of Travis Bickle and of our main character, Howard Ratner, sharing a claustrophobic intensity exemplified by the Safdie’s insistence on a camera front-and-center in the frenetic action. The most evident choice is Ratner’s jewelry store, this small, boxy, high-security showroom where a dozen people pack into the small space and chatter, yell, and gesticulate to the point where the viewer is amused, stressed, and exhausted.

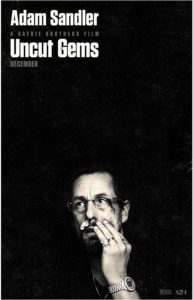

There is no greater example of this frenzied dialogue—the Safdies’ script was over 160 pages—than in the jewel-store owning, debt-owing, fast-talking protagonist Howard, played by Adam Sandler. Frequently Howard maneuvers through scenes spouting long bits of exposition as other characters talk at him, the phone rings, the door alarm goes off, or a myriad of other distractions happen in quick succession. The thrill and intensity of the movie are in its insistence on pushing forward as Howard constantly finagles and connives to achieve the big score on a black opal he obtained from Ethiopian Jews. And Sandler never lets up. He gives Howard a charisma and likability that belies his goal of winning and coming out on top.

This, perhaps, is the cardinal analog between the Safdies and Scorsese. Both craft characters that are driven by their egos and, like a character from the Book of Judges, often do what is right in their own eyes for their own skewed objectives. Left in the wake is someone like Howard’s son, who mournfully eyes his father as he distractedly watches a basketball game on which he has a huge wager. Or it is Raging Bull’s Vickie La Motta, the wife of Robert DeNiro’s Jake La Motta, who receives Jake’s abuse and jealous rage as he likens her to another title he needs to defend from the wandering eyes of possible competing men? Both characters reap tragic endings befitting the seeds they have sown.

However, what makes Uncut Gems different and exceptional—not that Raging Bull isn’t exceptional—is how Sandler is able to ground the character of Howard amidst the intensity. While we don’t root for DeNiro’s La Motta or Travis Bickle, we pull for Howard to score big. Sandler’s innate likability makes Howard’s fast-talking, caustic antics somewhat endearing, an eponymous “uncut gem” in his rough exterior but enchanting interior. It’s why, towards the end when Howard has found a way out of the mess only to dive right back in, it’s all the more painful to endure. We are so often waiting for something to go right for Howard that when it actually does, his conscious choice to put himself and others at risk again for the possibility of “winning” brings a charley horse level of re-tensing.

Ultimately, despite how we think the narrative should go, Howard’s calculating and hedging again pays off. The bet he places strikes big and it finally looks like he’s got his reward. But it’s all taken away in a surprising, grisly twist at the end: one of his debtor’s toughs has had enough of his antics and his chance to win disappears in a puff of gunsmoke and splatter of blood. The elusive payday he was seeking is snatched away and the ultimate consequence for his actions has been paid. The viewer is left to reflect on the cosmic scope of Howard’s story as—in my favorite shot of the movie—the camera enters the bullet hole and into a shot of a starry sky.

One cannot help but scale the movie’s story to a metaphysical and theological plane based on the final, celestial frame. Howard’s prideful prosperity is juxtaposed against the lone plaintive scene in the whole movie when Howard’s family, who is Jewish, celebrates the Passover seder together. As Howard’s mother recites the Hebrew word for each plague, Howard restates them in English. His recitation of all ten plagues drives home what can happen to the prideful, as Pharaoh’s own hard-heartedness led to pestilence, plague, and death.

Uncut Gems stresses, as it stresses us out, that “when pride comes, then comes disgrace,” (Proverbs 11:2). All of our grasping for the things of this world can be taken away in an instant. To quote The Preacher, “I have seen everything that is done under the sun, and behold, all is mere breath and a striving after wind,” (Ecclesiastes 1:14). All of our efforts can produce great results and we can achieve great fame, but it will not last. Our big score can turn into a big hurt. Winning Game 7 of the Eastern Conference Semifinals, as Kevin Garnett does in this movie—in a surprisingly great performance—might mean little when we lose to the LeBron-led Miami Heat in the Finals. Money, fame, love… it is all a mere breath, and in the end, “all has been heard. Fear God and keep his commandments, for this is the whole duty of man.” (Ecclesiastes 12:13b)