The Dread and Spectacle of Oppenheimer (2023)

“You can’t lift the stone without being ready for the snake that’s revealed.”

—Nils Bohr, Oppenhiemer

In my previous article, I argued that modern moviegoers crave creative, original, and risky new movies that lean more towards art, history, and humanity, and less towards fantasy and unreality. Oppenheimer had me hoping for something original, something different, and, if we were fortunate, something masterful in the pantheon of historical epics.

In my previous article, I argued that modern moviegoers crave creative, original, and risky new movies that lean more towards art, history, and humanity, and less towards fantasy and unreality. Oppenheimer had me hoping for something original, something different, and, if we were fortunate, something masterful in the pantheon of historical epics.

It’s safe to say that with Oppenhiemer, we got such a film.

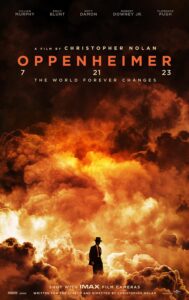

It’s definitely worth seeing in theaters, IMAX if you can. It was envisioned, filmed, and produced for the big screen, and seeing it in my local theater (twice) was well worth the time and money. Be warned—it’s not for the faint of heart. It has thrills, it has intensity, it has audiovisual loudness. But, most poignantly for me, it has dread. Thick, ever-present, heart-sinking, inescapable dread.

Dread, fear, doubt, and even some well timed suspense (horror? Not quite, but for Nolan this is pretty intense stuff) are pervasive and pitch perfect, and harken back to the feelings I experienced in the theaters enduring Dunkirk for the first time. Oppenheimer is not a 3 hour thrill ride, that’s for sure, but it is dramatic, suspense peppered filmmaking at its finest. Nolan always delivers thrills with high octane (and gorgeous) movie moments, and, despite the sparsity of action throughout this type of dramatic narrative, these moments still managed to leave me breathless. He’s a master of the art of the sequence buildup, and does tension with sometimes claustrophobic camera work, tight facial shots, wide area sweeps over huge set pieces, and ethereal lighting unlike many others of his caliber.

That said, the movie is admittedly long with an unsteady pace at the start and the end (there are more than a few moments when I wanted to take a restroom break, put on subtitles, and pause). The dialogue is sometimes difficult to comprehend, and the lack of action sequences typical of Nolan blockbusters (while understandable in the case of a biopic) is glaring.

By contrast, the best act of the movie takes place at the infamous Los Alamos military complex in New Mexico, following two very straightforward timelines leading up to a huge moment. The act is a flawless example of how to pace and edit and write a movie to be deliberately stressful. It’s tense, sweeping, gives you a great sense of scale and urgency, and climaxes in such a way that your heart won’t stop racing until after it’s over. I love filmmaking like this, and find it so refreshing to see that highly artistic and beautiful, CGI-free scenes of epic proportions still have a place in contemporary cinema.

By contrast, the best act of the movie takes place at the infamous Los Alamos military complex in New Mexico, following two very straightforward timelines leading up to a huge moment. The act is a flawless example of how to pace and edit and write a movie to be deliberately stressful. It’s tense, sweeping, gives you a great sense of scale and urgency, and climaxes in such a way that your heart won’t stop racing until after it’s over. I love filmmaking like this, and find it so refreshing to see that highly artistic and beautiful, CGI-free scenes of epic proportions still have a place in contemporary cinema.

All of which contributes to Oppenheimer telling a detailed and polarizing story, a story that our main character doesn’t really mean to live out in the way he’s presenting himself.

Cillian Murphy, who inhabits that main character, has had an interesting career as an actor playing smaller roles in big time Nolan blockbusters, such as the Dark Knight trilogy and Dunkirk, as well as finding great success in the lead role of Peaky Blinders. Now, he’s being universally praised for his portrayal of the famous physicist, lauded for his dedication to the role (and physical resemblance to the man). He fully deserves this recognition, since his tortured attitude and sense of genuine dread throughout the movie are pitch perfect, and set the tone for all the supporting characters. Robert Downey Jr., Florence Pugh, Matt Damon, Emily Blunt, and Alden Ehrenreich all serve up exquisite performances as well, with Downey Jr. acting as the vindictive yet soft-spoken antagonist, a character he clearly relished inhabiting (more villainous, anti-Iron-Man roles, please).

Acting aside, the film could also serve as a masterclass in sound mixing, cinematography, effective use of the musical score, and how to create and maintain tension in the atmosphere of a scene. Certain sequences utilize the music, sound effects, and camera angles to such chilling and unsettling effect that you’ll find yourself needing to look away, to possibly avoid the horror and discomfort of what’s happening, even though it happens mostly off screen. There’s a brilliant sequence in an auditorium where the sound editing is so jarring and unsettling that it seems lifted right out of cerebral horror film. Nolan is also extremely clever with visuals, and seems to know exactly what not to show the audience just as much as what to focus on.

Acting aside, the film could also serve as a masterclass in sound mixing, cinematography, effective use of the musical score, and how to create and maintain tension in the atmosphere of a scene. Certain sequences utilize the music, sound effects, and camera angles to such chilling and unsettling effect that you’ll find yourself needing to look away, to possibly avoid the horror and discomfort of what’s happening, even though it happens mostly off screen. There’s a brilliant sequence in an auditorium where the sound editing is so jarring and unsettling that it seems lifted right out of cerebral horror film. Nolan is also extremely clever with visuals, and seems to know exactly what not to show the audience just as much as what to focus on.

The score, by the truly talented Ludwig Göransson, is a wonder of strings, brass, synths, and orchestral flair. Tension, drama, beauty, and dread are all heightened to almost unbearable levels, and scenes are given the musical momentum and passion to drive forward with intense and moving power.

Rich in history, period-accurate down to the most minuscule detail (this is Nolan we’re talking about!), and packed with hard, heavy questions of our past and present, the movie shines as a great original story amongst the wasteland of remakes, sequels, and stale “content.” Even with the polarizing reactions and studio conflicts of Tenet in 2020, it appears that Nolan can do no wrong (from a business perspective at least), since not even his most baffling and complex films avoid piles of money.

There has been some backlash regarding the erasure of asian voices from the film, and it’s obvious that the movie is not interested in showing the damage done to the Japanese people by the bombs. This is an uncomfortable truth, and even nearly 80 years later, the bombings of those two great cities is a disturbing chapter of history many Americans would like to simply forget.

“Miya Sommers is a fifth-generation Japanese American living in Oakland who doesn’t plan on seeing Oppenheimer. Sommers’ grandfather lived in a town outside of Hiroshima when the atomic bomb hit, killing several of her family members. ‘I’m feeling more and more resistant to wanting to pay money to sit through that, knowing that it’s going to be pretty traumatizing. I don’t care about [Oppenheimer’s sense of] guilt. Basically my whole family is dead because of him.’”

—Olivia Cruz Mayeda for KQED.org

In this film, we see only the closeness of our protagonist, warts and all, and almost every event is witnessed strictly from his perspective. Oppenheimer sees the science, understands the risks, feels the weight of his work and how it may be used with such unfathomable devastation. And he sees the aftermath—on black and white film only.

In this film, we see only the closeness of our protagonist, warts and all, and almost every event is witnessed strictly from his perspective. Oppenheimer sees the science, understands the risks, feels the weight of his work and how it may be used with such unfathomable devastation. And he sees the aftermath—on black and white film only.

Now, does this type of zoomed in approach honor the victims of the atomic attacks of 1945? Is this important when considering the film is about the man who gave the US military the power to wipe out cities? I think yes, but Nolan chose not to make it the point of the movie; instead the point is an examination of our “American Prometheus,” a man who was arguably the most influential human to have ever lived.

Robert Oppenheimer is a fascinating study of how a brilliant but flawed man can change history forever, and how he struggles to accept his responsibility for the horror and pain perpetuated by his discoveries. Sin will tell the pragmatist that the ends justify the means, and sin will convince even the most morally upstanding people that blame should rest on others, and that tragic events like the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were unfortunate necessities of war. The atom bomb was a trump card, and the nuclear option forced the Japanese to surrender, potentially saving countless American and Japanese lives. While there is much debate about the necessity of these weapons, it is clear that such power and terror must forever alter the world, and that once the (nuclear) genie is let out of the bottle, it can never go back in.

And it forces us to ask a crucial question: is God a God of peace, or of war? Could He be both? The Old Testament speaks to the topic extensively:

“…[When God defeats] seven nations more numerous and mightier than you, and when the Lord your God gives them over to you, and you defeat them, then you must devote them to complete destruction. You shall make no covenant with them and show no mercy to them.”

“And you shall consume all the peoples that the Lord your God will give over to you. Your eye shall not pity them, neither shall you serve their gods, for that would be a snare to you.”

—Excerpts from Deuteronomy 7

“Do I not hate those who hate you, O Lord?

And do I not loathe those who rise up against you?

I hate them with complete hatred;

I count them my enemies.”

—Psalm 139:21-22

What do we as Christians in the 21st century make of these parts of the Bible? The answer comes into greater focus when the New Testament is brought to bear on what is being said to Old Testament Israel. 18th-century Bible commentator Matthew Henry compares the destruction of these evil nations to the destruction of sin in the hearts of believers: these wicked Amorites were the enemies of Israel, the enemies of God, and the preordained recipients of God’s righteous wrath.

What do we as Christians in the 21st century make of these parts of the Bible? The answer comes into greater focus when the New Testament is brought to bear on what is being said to Old Testament Israel. 18th-century Bible commentator Matthew Henry compares the destruction of these evil nations to the destruction of sin in the hearts of believers: these wicked Amorites were the enemies of Israel, the enemies of God, and the preordained recipients of God’s righteous wrath.

“The righteous God has determined that they shall not be cut off till they have persisted in sin so long, and arrived at such a pitch of wickedness, that there may appear some equitable proportion between their sin and their ruin…”

So, in the context of Old Testament Israel, the wars fought against the nations inhabiting the Promised Land were not only just, but divinely ordained with predetermined outcomes, and pointing forward to a greater reality.

This means that looking at the people of God winning in battle and then claiming that America had every right to invent, deploy, and proliferate nuclear weapons because we too are “the people of God” is asinine; nowhere in the New Testament does God command His Church to take up arms against the enemies of God like the Old Testament Isrealites did, since Christ Himself is our new defender, our warrior king.

That warrior king commands us to love our enemies, and yet He also condemns the wicked Pharisees who are exposed as hypocrites and sons of Satan, destined for judgment. Jesus is both savior and swordbearer, warrior and shepherd, loving friend to the righteous and ferocious fighter of the unrighteous. Sinners and evil will be punished, and Jesus will be the sword-bearing warrior that condemns them, which is why we don’t need to be that warrior.

This theology of divine judgment seems to have become distasteful and unpopular in our modern era, but consider that most of us would relish the destruction and judgment of our political, ideological, and civil enemies. Should we be quick to judge, quick to desire destruction? Or slow to anger? How much better are we if we needed to be rescued from our sinful ways? The dread of the A-bomb is nothing compared to the dread of that divine judgment; and without Christ, it’s aimed at all of us.

This theology of divine judgment seems to have become distasteful and unpopular in our modern era, but consider that most of us would relish the destruction and judgment of our political, ideological, and civil enemies. Should we be quick to judge, quick to desire destruction? Or slow to anger? How much better are we if we needed to be rescued from our sinful ways? The dread of the A-bomb is nothing compared to the dread of that divine judgment; and without Christ, it’s aimed at all of us.

The gospel is the opposite of dread: it’s the good news that hell and the powers of evil have lost, that Christ is victorious, and that we no longer must live and die in bondage to sin. It’s a call to believe in the name of Jesus, and repent and be redeemed by His atoning sacrifice on the cross.

We live in a time of dread, of technological wonders (and terrors), of evil men making vile threats, and of decent humans fighting desperately to persevere, which prompts so many questions.

Is the use of weapons of mass death justifiable? Can we lay blame on J. Robert Oppenheimer for creating an awesome and horrific weapon that has the potential to destroy millions? Is there any moral purity in designing a death machine without possessing the power necessary to avoid using it? Should we protest nuclear weapons, and decry war of any kind?

There’s no easy answers here, but I wish I could give you some.

All I can give you amid this dread is some certainty:

“I am sure that neither death nor life, nor angels nor rulers, nor things present nor things to come, nor powers, nor height nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord.”

—Romans 8:38-39

• • •

A longer version of this article has been published here.