The Beloved Bombs of Paul Williams: Phantom of the Paradise (1974) Meets Bugsy Malone (1976)

Paul Williams was on quite a roll in the early 1970s. He’d written monster hits for groups like The Carpenters (“We’ve Only Just Begun”) and Three Dog Night (“An Old Fashioned Love Song”) and become a near-regular on The Tonight Show, once appearing in his full Battle for the Planet of the Apes make-up to croon “Rainy Days and Mondays.” A truly great moment in late-night TV history. Before the decade was up, Paul would win an Oscar for co-writing “Evergreen” in Streisand’s A Star Is Born and play a key role in launching The Muppets into the mainstream. The man was everywhere and then—poof!—nowhere. His substance-abuse-induced disappearance in the 80s and 90s would prove so conspicuous that it inspired filmmaker Stephen Kessler to title his 2011 documentary Paul Williams Still Alive.

Paul Williams was on quite a roll in the early 1970s. He’d written monster hits for groups like The Carpenters (“We’ve Only Just Begun”) and Three Dog Night (“An Old Fashioned Love Song”) and become a near-regular on The Tonight Show, once appearing in his full Battle for the Planet of the Apes make-up to croon “Rainy Days and Mondays.” A truly great moment in late-night TV history. Before the decade was up, Paul would win an Oscar for co-writing “Evergreen” in Streisand’s A Star Is Born and play a key role in launching The Muppets into the mainstream. The man was everywhere and then—poof!—nowhere. His substance-abuse-induced disappearance in the 80s and 90s would prove so conspicuous that it inspired filmmaker Stephen Kessler to title his 2011 documentary Paul Williams Still Alive.

But that’s still on the horizon in the early 1970s. Before flaming out, Williams would shape four of that decade’s most memorable movie musicals: Phantom of the Paradise, Bugsy Malone, A Star Is Born and The Muppet Movie. It was a period during which the genre underwent something of a subversion. Rodgers and Hammerstein were ancient history, and Sondheim was becoming passé. Hair, meanwhile, had taken Broadway by storm, and Hollywood took notice. Following the box office success of Andrew Lloyd-Weber’s Jesus Christ Superstar, producers began scrambling for countercultural musicals they could film.

Rocky Horror Picture Show would be the most well-known project to emerge from this free-spirited renewal. And yet more than a year before Barry Bostwick and Susan Sarandon would be filmed knocking on the door of “the Frankenstein Place,” Brian de Palma cooked up a transgressive spectacle of his own, Phantom of the Paradise.

Watching the finished product, one can only imagine how those initial development meetings went. De Palma, the auteur, still fresh from his indie collaborations with a young Robert De Niro, convincing executives to bite on a bizarre mish-mash of Phantom of the Opera, Dorian Gray, and Faust, with songs from a guy most well-known for square ballads like “You and Me Against the World.”

The plot of the film is almost beside the point. After an uncredited opening voiceover by none other than Rod Serling, we watch a gangly composer named Winslow Leach get cheated by Swan, a Phil Spector-like pop svengali played by Paul Williams himself. Soon thereafter a record press mishap disfigures Leach, transforming him into a ghoul bent on revenge. Then there’s a young singer (a pre-Stardust Memories Jessica Harper), who finds herself caught in the two men’s crossfire. All this as the wider cast prepares for a musical-within-a-musical to open Swan’s new venue, The Paradise.

The plot of the film is almost beside the point. After an uncredited opening voiceover by none other than Rod Serling, we watch a gangly composer named Winslow Leach get cheated by Swan, a Phil Spector-like pop svengali played by Paul Williams himself. Soon thereafter a record press mishap disfigures Leach, transforming him into a ghoul bent on revenge. Then there’s a young singer (a pre-Stardust Memories Jessica Harper), who finds herself caught in the two men’s crossfire. All this as the wider cast prepares for a musical-within-a-musical to open Swan’s new venue, The Paradise.

Suffice to say, it doesn’t end well for anyone. (Except, perhaps, for visionary French dance music duo Daft Punk, who modeled their headgear on the titular character’s awesome helmet.) Along the way there’s some top-notch musical pastiche, unbelievable sets, and lighting that would make Frank Tashlin swoon. Phantom of the Paradise drips with eccentricity, technical razzle-dazzle, and what many would call an overabundance of ideas.

Doubtless de Palma was commenting on his own Faustian experience in post-hippy Hollywood. Commerce and art, the film implies, may feed on each other but cannot ultimately co-exist. The attempt to reconcile the two results in pandemonium and destruction. In his closing song, Williams underlines de Palma’s passionate moral vision in the brilliant, jaunty “The Hell of It”:

Life’s a game where they’re bound to beat you

And time’s a trick they can turn to cheat you

And we only waste it anyway and that’s the hell of it

The imagery wasn’t chosen arbitrarily, as the final act reveals Beelzebub himself to have been pulling the strings all along. Moreover, the introduction of a faux-priest into the staging of the cacophonous finale suggests a deeply cynical view of religion (and matrimony) as simply one more prop to bolster self-interest—even if the realities of good and evil, to which it attests, aren’t fictitious. Phantom of the Paradise paints a picture of the world as “territory occupied largely by the devil,” as Flannery O’Connor once put it.

The imagery wasn’t chosen arbitrarily, as the final act reveals Beelzebub himself to have been pulling the strings all along. Moreover, the introduction of a faux-priest into the staging of the cacophonous finale suggests a deeply cynical view of religion (and matrimony) as simply one more prop to bolster self-interest—even if the realities of good and evil, to which it attests, aren’t fictitious. Phantom of the Paradise paints a picture of the world as “territory occupied largely by the devil,” as Flannery O’Connor once put it.

Which isn’t to suggest that there’s zero redemption on offer. The “music lingers on,” we are told, even when the musician’s hopes do not. The same could be said for Phantom itself. Upon initial release, the movie tanked dramatically. Everywhere, that is, except for the Canadian city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, where it outsold Jaws and where rapturous screenings are still held today. Something about the film—maybe the ingenuity, maybe the wit, maybe the songs, maybe the sheer weirdness, maybe the not-so-subtle anti-corporate-America vibe—struck a chord in this isolated Nazareth of a town, yielding what can only be called lasting joy. Indeed, the highly localized enthusiasm has now spawned a documentary of its own, The Phantom of Winnipeg, which hits (very) select theaters this summer.

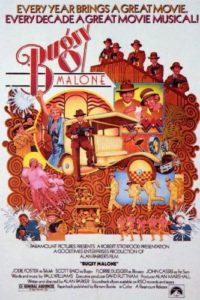

Williams’ next silver-screen project would prove equally singular, if much more light-hearted. I’m referring to 1976’s Bugsy Malone, the debut film by Alan Parker, the British director who a few years later would bring us The Wall. The conceit this time around was no less unorthodox: a musical about Prohibition-era Chicago gangsters, starring an all child cast, lip-syncing to songs sung by adult voices. Think Newsies meets Little Rascals meets Guys and Dolls with a thin overlay of Britishness. It shouldn’t work, and I’m not sure it ultimately does. You could say that Bugsy comes off more as a movie-length stunt than an actual movie, and you wouldn’t be wrong. Still, the performances by a 13 year-old Jodie Foster and 15 year-old Scott Baio are nothing if not charming, and Williams’ songs are pitch-perfect.

Again, the plot is largely dispensable, though peppered with cute touches. Two rival gangs compete for dominance over the city’s various “rackets” (sarsaparilla, groceries, ha ha ha), using as their weapons “splurge guns”, AKA tommy guns which fire ping-pong balls that explode with whipped cream, incapacitating whatever crosstown hoodlum comes near. Scott Baio plays Bugsy, a lovable loner with a knack for being in the right place at the right time.

Again, the plot is largely dispensable, though peppered with cute touches. Two rival gangs compete for dominance over the city’s various “rackets” (sarsaparilla, groceries, ha ha ha), using as their weapons “splurge guns”, AKA tommy guns which fire ping-pong balls that explode with whipped cream, incapacitating whatever crosstown hoodlum comes near. Scott Baio plays Bugsy, a lovable loner with a knack for being in the right place at the right time.

The film follows a similar musical-within-a-musical format to Phantom. Instead of The Paradise Theater, here the backdrop is Fat Sam’s Speakeasy, a nightclub that welcomes where The Paradise menaces. The choreography trades the madcap energy of Phantom for an equally uncomfortable precociousness (witness: pre-pubescent Jodie Foster slinking around the stage in her slip, winking about her unrivalled “skills”). Again, how this one got greenlit is a marvel.

Yet what makes the two films such natural companions—other than Williams’ undeniable way with a lyric—lies in their climactic scenes. In Phantom the principal characters convene on the theater to celebrate, but instead end up rioting in a murderous festival of debauchery and madness. In Bugsy, the characters converge on Fat Sam’s to snuff each other out but end up celebrating! “We’re weaker divided / Let friendship double up our powers,” belts the cast rapturously as meringue covers everything in sight. A new beginning for all involved, washed white as whipped cream.

Both visions are self-consciously silly. Both revel in their excesses. But in De Palma’s, the veneer of sophistication masks criminality and chaos, and only art has lasting merit. Parker flips the script, casting criminality as a precursor to repentance, redemption, and, well, love. Art, in the latter instance, is more like play than life-or-death.

Bugsy bombed in America, but like Phantom, gained peculiar traction elsewhere, this time in the United Kingdom, where it became a favorite musical for school children to put on. No less than director Edgar Wright credits a grammar-school production of Bugsy with introducing him to show business. (He paid tribute by casting Paul Williams in a Bugsy-like role in his hit 2017 film Baby Driver).

The theology of these films is admittedly thin. Perhaps the deepest lesson to be drawn has to do, not with their narrative inversions, but with their reception. Meaning, in God’s world, what we think is going on—what we think a creative act “accomplishes”—and what’s really going on are often two different things. In fact, a bad idea is often a good idea. The Spirit blows where it will and doesn’t require reasonable or even comprehensible subject matter to fashion meaning and joy.

In a logical world, governed by rational decision-making, neither of these films would have been made. Neither has any reason to exist other than sheer gratuity. Perhaps, then, they illustrate the deeper miracle of life in God’s world. Not that you and I have to be here, or should be here, but that we are here, warts and quirks and compulsions and all. Existence itself is grace.

Adel Bestavros once defined hope as “patience with self” and faith as “patience with God.” What he meant, I think, is that just because joy isn’t here today doesn’t mean it’s not coming, or that God’s activity is over. Williams, after all, would re-emerge from his personal hell in the early 2000s, with a ministry to fellow addicts the world over, a gift given out of all that Phantom-like chaos and self-destruction1. After all, for a while there, it looked very much like Paul was going the same way as Swan, who was a casualty of his own ego and avarice. Thankfully, the “Big Amigo,” as Paul now terms his higher power, had more of a Bugsy ending in mind. No whipped cream but a “Rainbow Connection” nonetheless.

Adel Bestavros once defined hope as “patience with self” and faith as “patience with God.” What he meant, I think, is that just because joy isn’t here today doesn’t mean it’s not coming, or that God’s activity is over. Williams, after all, would re-emerge from his personal hell in the early 2000s, with a ministry to fellow addicts the world over, a gift given out of all that Phantom-like chaos and self-destruction1. After all, for a while there, it looked very much like Paul was going the same way as Swan, who was a casualty of his own ego and avarice. Thankfully, the “Big Amigo,” as Paul now terms his higher power, had more of a Bugsy ending in mind. No whipped cream but a “Rainbow Connection” nonetheless.

David Zahl is director of Mockingbird Ministries and author of the new book from Fortress Press, Seculosity: How Career, Parenting, Technology, Food, Politics, and Romance Became Our New Religion and What to Do about It. He can also be heard talking about grace and music on The Mockingcast & The Well of Sound. He resides in Charlottesville, Virginia with his wife and three boys.

- Paul’s sense of humor did not abandon him during his two decades-ish out of mind. Accepting the Grammy award on behalf of Daft Punk in 2014, with whom he’s now a collaborator as well as an inspiration, he said, “Back when I was drinking and using I used to imagine things that weren’t there and were frightening, then I got sober and two robots called me and asked me to make an album.” Still alive, indeed.

Pingback: Another Week Ends: The Space Race (and Grace), Professional Christian Burnout, Screen Addictions and Abstinence, Truth and Martyrdom, the Holies of Hollywood, and the Modern Leper | Mockingbird