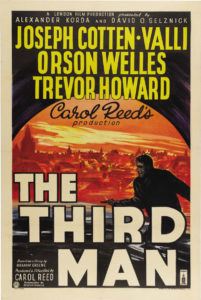

Reviewing the Classics| The Third Man

It’s always a good day when you can dig into Film Noir, and The Third Man is a prime example of the artful genre. Martin Scorsese is said to be a big fan of the film– enough to write a major thesis on it when he was in film school. He got a B+ for it, and his tutor remarked, “Forget it, it’s just a thriller.”

It’s always a good day when you can dig into Film Noir, and The Third Man is a prime example of the artful genre. Martin Scorsese is said to be a big fan of the film– enough to write a major thesis on it when he was in film school. He got a B+ for it, and his tutor remarked, “Forget it, it’s just a thriller.”

This mere “thriller” was released in 1949 and follows a mystery in post-war Vienna. Joseph Cotten (who starred in my favorite Hitchcock film, Shadow of a Doubt) plays the lead character, Holly Martins. Even the other characters in the film think his name was strange.

Holly comes to Vienna from America at the bidding of his friend, Harry Lime. Harry claims to have a job for Holly, but within hours of arriving, Holly discovers that Harry is dead and his funeral is currently in play.

Men who had lived through the war and the aftermath in Europe were the ones who created The Third Man. Director Carol Reed worked for the British Army documentary unit, while writer Graham Greene was said to have been a spy. At the time, Vienna was split into four sectors: British, American, Russian, and French. Holly discovers that Harry was under investigation by the occupying British military. Dissatisfied with their assertions of Harry’s character and death, Holly decides to tackle the investigation in his own way.

Unlike the other characters in the film, who come off as shifty or untrustworthy, Holly stands out as the “American hero” type idolized at the time. He is an optimistic every man who will fight for truth and justice for his friend. He comes to Europe for the job offered to him, but he stays because he takes on the mindset that he can just barge in and save the day. Holly learns very quickly – as America did when we entered the war – that nothing is that simple. The world is a game of light and shadows, and as the movie reveals, it’s hard to discern which is which at first glance.

On that note, my personal favorite aspect of this film is the intense use of visuals and repetitious images to convey an atmosphere of claustrophobia, of being ensnared in this city and its four occupying nations. The shots are masterfully framed, coupled with the classic noir lighting. The imagery of lines and bars constantly comes into play. In my second viewing, I was very aware of it and admired the artistry of using lines in architecture and nature to make both the characters and audience feel trapped. Window casements, crib bars, Ferris Wheels, trees, railings – you will find lines and bars in almost every scene.

The other repeated image is stairwells and tunnels, also adding to the growing tension of being trapped with nowhere to go. We see the vanity of running up or down a stairwell, or to either end of a tunnel, only to find “enemies” waiting for you on the other side. Though the cinematography does show the beauty of the city, The Third Man paints Vienna not as the cultural paradise we know it, but as a postwar prison in which everyone is an inmate – even those who serve the four governing forces.

The other repeated image is stairwells and tunnels, also adding to the growing tension of being trapped with nowhere to go. We see the vanity of running up or down a stairwell, or to either end of a tunnel, only to find “enemies” waiting for you on the other side. Though the cinematography does show the beauty of the city, The Third Man paints Vienna not as the cultural paradise we know it, but as a postwar prison in which everyone is an inmate – even those who serve the four governing forces.

Robert Krasker – the film’s award-winning cinematographer – gives us a subtly innovative cinematic style. His use of tilting the camera brings a sense of power to certain characters at certain moments. I noticed in the beginning, Holly was often filmed from a downward angle, suggesting a lack of control. As the film continues, we see him in a more upward angle, to accommodate his breakdown of the mystery of Harry Lime and the power that gives him. The use of wide-angle lenses provides an additional sense of distortion on particular characters. Even though the mystery is not overtly intense, the creativity of the visual scope carries the suspense.

In one of the most iconic character entrances in film history, Harry Lime (Orson Welles) reveals that he is, in fact, still alive. This unravels the mystery, as well as Holly’s opinion of him. Holly learns that Lime has been doing all the horrible things the British military have claimed. He watered down penicillin to stretch the drug and sold it to vulnerable hospitals. They used it unknowingly on children, bringing them a fate worse than death. Lime had been taking advantage of the Viennese struggle and became part of the black market for goods exchange happening under the city’s table.

Though Orson Welles’ performance in this film is fantastic, he was never known as being an easy man to work with. Not only did he show up late for the shoot, he complained about the conditions he was expected to work in, particularly the famous Vienna sewer chase – an utterly brilliant scene. Welles was commonly known for being full of himself, and unlike the other cast members who spent time enjoying the city, signing autographs for fans, or handing out food parcels to Austrian children (like Joseph Cotten did), Welles was rarely in their loop.

Even with some of that behind-the-scenes tension, The Third Man came together beautifully. It’s just the right blend of being suspenseful, but not gimmicky, and smart without being overwrought. Though a good chunk of the dialogue is in German, you really don’t feel as though you’re missing anything. The rest of the dialogue is very well-written and cleverly expository without being on-the-nose.

Even with some of that behind-the-scenes tension, The Third Man came together beautifully. It’s just the right blend of being suspenseful, but not gimmicky, and smart without being overwrought. Though a good chunk of the dialogue is in German, you really don’t feel as though you’re missing anything. The rest of the dialogue is very well-written and cleverly expository without being on-the-nose.

The Third Man is unique for many reasons, but I think its last shot is particularly memorable. The film begins and ends with Lime’s funeral, each a separate occasion. The story is sort of sandwiched between the two funerals for the same man. In some ways, it seems like all the chaos in-between is all for naught because the outcome delivers a bittersweet “all is vanity” motif.

However, the point of the film is not to give a happy ending, even though writer Graham Greene wanted that. As a viewer, I believe the point of The Third Man is to offer a different perspective on the aftermath of WWII, and that all opposing sides have their reasons for believing they are right. One city was utterly divided because of the stubbornness of nations, and nothing good came from it. Though changed forever, the characters begin and end the film alone. This is a reminder of the destructive distrust and cynicism that comes from war, and it also serves as a warning to future generations to never bring such strife and division upon the world again.

To put it in a colloquialism, The Third Man is a slow burn, but I consider it a masterpiece because of that. The longer you let it simmer in your mind, the more deliciously understood the film becomes. It is a snapshot of history that we should not soon forget, and a piece of pioneering visual cinema that we will continue to study and admire for generations to come.