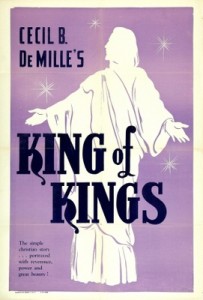

Reviewing the Classics | The King of Kings

Cecil B. DeMille’s depiction of the life of Christ is “a reverent spectacle.” The silent film embodies both piety and theatrics, and features a tranquil Christ in the midst of a melodramatic world. DeMille’s nearly 3-hour epic features scenes and Scripture references from all four canonical Gospels, and has a tone of extravagance accompanied by a spiritual admiration for its subject.

Cecil B. DeMille’s depiction of the life of Christ is “a reverent spectacle.” The silent film embodies both piety and theatrics, and features a tranquil Christ in the midst of a melodramatic world. DeMille’s nearly 3-hour epic features scenes and Scripture references from all four canonical Gospels, and has a tone of extravagance accompanied by a spiritual admiration for its subject.

The opening scene features Mary of Magdala at a lavish banquet surrounded by fawning male suitors, frustrated that her lover, Judas, has chosen to follow a lowly carpenter from Nazareth instead of her indulgent lifestyle. This entire sequence lacks any biblical basis, but it sets the tone for the film—this will be a dramatic, exuberant telling of the Christ narrative, with a huge production and vivid imagery. The majority of the dialogue and narration are direct quotes from Scripture, including the references on the screen. There are powerful and memorable images—the casting out of the seven demons from Mary Magdalene; the healing of a lunatic child; Jesus carrying a lonely sheep out of the temple; Jesus unknowingly working as a carpenter on a Roman cross. Characters and settings are often set up in the frame like Renaissance paintings, where physical movement and posture communicates the drama of the scenario more than spoken dialogue. The finale on Calvary with the crucifixion is nearly a disaster movie, with lightning, thunder and earthquakes which swallow up bystanders as the temple curtain is torn from a blast of lightning. It’s all a bit over-the-top, but this is DeMille, a master of the extravagant epic.

The Jesus of The King of Kings is a kindly Christ, both calm and powerful. He is esoteric and otherworldly, rarely showing much emotion as the camera bathes him in whitening light. He’s often shown slightly glowing and the brightest point in the frame, drawing all attention towards him in reverential awe. There are very few moments of  teaching or sermons, and the emphasis is on Jesus the healer—the very first time we see Jesus is through the opened eyes of a blind child, and even on his way to Calvary, he pauses while carrying the cross to heal a band of lame beggars in an alleyway. H. B. Warner, who would go on to play roles in It’s a Wonderful Life, Sunset Blvd., and The Ten Commandments, portrays Jesus with a peaceful stoicism, a calm confidence about his mission of healing and grace. This portrayal leans more towards the divine nature of Christ rather than his humanity, and one wouldn’t be surprised to see him floating off the screen in shining, holy radiance. The final scene of the ascended Christ shows him framed against a modern cityscape with the promise that he will be “with you always.” It’s a significant image, as DeMille’s film seems to take the Great Commission seriously to take the Gospel message to the ends of the earth.

teaching or sermons, and the emphasis is on Jesus the healer—the very first time we see Jesus is through the opened eyes of a blind child, and even on his way to Calvary, he pauses while carrying the cross to heal a band of lame beggars in an alleyway. H. B. Warner, who would go on to play roles in It’s a Wonderful Life, Sunset Blvd., and The Ten Commandments, portrays Jesus with a peaceful stoicism, a calm confidence about his mission of healing and grace. This portrayal leans more towards the divine nature of Christ rather than his humanity, and one wouldn’t be surprised to see him floating off the screen in shining, holy radiance. The final scene of the ascended Christ shows him framed against a modern cityscape with the promise that he will be “with you always.” It’s a significant image, as DeMille’s film seems to take the Great Commission seriously to take the Gospel message to the ends of the earth.

Overall, The King of Kings is remarkably faithful to the Biblical text while having a unique and grand aesthetic. It’s a spectacle, to be sure, and some of the more melodramatic acting moments are almost laughable to modern audiences. However, its flamboyant production has a sense of bigness, a grandeur fit for the exalted King of Kings and Lord of Lords. DeMille was proud that his film became the most widely viewed Jesus film in the world in the first half of the 20th century, and it’s certainly a Jesus film worth seeking and watching today.

The King of Kings is available through the Criterion Collection and is one of the Criterion movies available with a subscription to Hulu Plus.