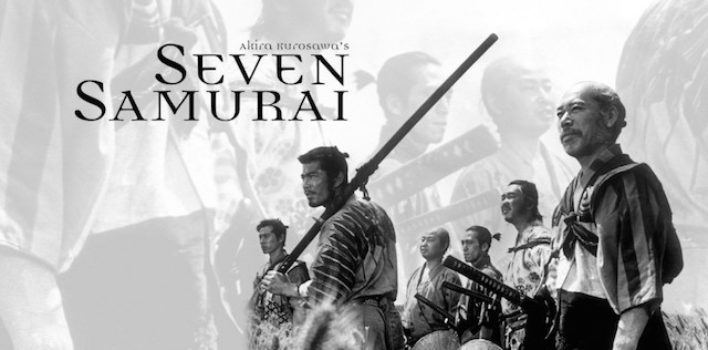

Reviewing the Classics| Seven Samurai

Seven Samurai, directed and co-written by Akira Kurosawa, is a masterwork of filmmaking. Set in late-16th century feudal Japan, the backdrop for the story is one of upheaval and unrest. A poor farming village is under continual threat from pillaging bandits, and the farmers need to find some form of protection before the last crop is stolen–they need the help of samurai. Once the difficult and somewhat painful recruitment process is completed, seven rogue samurais, or ronin (those without a feudal lord to serve, without leader or loyalty), return to help the village; the group is a mix of skilled warriors, mediocre swordsman, one young trainee/disciple, and one crazy drunk who isn’t actually a real samurai. Despite initial tensions between the groups–caused by marked class distinctions, cultural biases, and past injustices on both sides–the samurai and the villagers learn to work together. Along with training them to fight, the samurai teaches the villagers bravery and unity.

Seven Samurai, directed and co-written by Akira Kurosawa, is a masterwork of filmmaking. Set in late-16th century feudal Japan, the backdrop for the story is one of upheaval and unrest. A poor farming village is under continual threat from pillaging bandits, and the farmers need to find some form of protection before the last crop is stolen–they need the help of samurai. Once the difficult and somewhat painful recruitment process is completed, seven rogue samurais, or ronin (those without a feudal lord to serve, without leader or loyalty), return to help the village; the group is a mix of skilled warriors, mediocre swordsman, one young trainee/disciple, and one crazy drunk who isn’t actually a real samurai. Despite initial tensions between the groups–caused by marked class distinctions, cultural biases, and past injustices on both sides–the samurai and the villagers learn to work together. Along with training them to fight, the samurai teaches the villagers bravery and unity.

At 3 ½ hours long, when Seven Samurai was released in 1954, it was the longest hit film since 1939’s Gone with the Wind (3 hours 42 minutes). Despite this, Kurosawa’s film doesn’t feel long (in contrast with Gone with the Wind, which feels like it lasts about six hours). In contrast to many Hollywood blockbusters these days, the length is not self-indulgent–far from it. Kurosawa masterfully uses the time to richly develop the characters and to absorb the audience in the world of the story. It also allows time for us to feel the passage of seasons in the narrative–highly central to a story about protecting the lives and livelihoods of farmers. Even more importantly, it provides space for friendship and camaraderie between characters and makes the depth of their bonds easy for us to understand as we watch them get to know one another–and as we learn to know them ourselves.

What forcibly struck me during my latest viewing of Seven Samurai is that there are multiple characters that fit into Shakespearean archetypes (which is perhaps one reason the film resonates with our Western cultural consciousness). Kurosawa’s film brought specific characters from Shakespeare’s As You Like It to mind. Kambei, played by Takashi Shimura, is the Duke: a wise wanderer past the prime of his life, searching for peace but still needing to fight. Kambei’s young disciple, Katsushiro (Ko Kimura), is Silvius: the young, romantic idealist who quickly falls in love surrounded by the pastoral landscape (though in this case, his “Phebe” needs little convincing to fall for him in return). And last but certainly not least, the character Kikuchiyo (Toshiro Mifune) follows the tradition of Shakespeare’s Fool (Kikuchiyo is the aforementioned “crazy drunk”). In As You Like It, he is Touchstone; in Twelfth Night, he is Feste; in King Lear, he is–well, the Fool. Kikuchiyo is the sad clown with a tragic past; he brings levity to the gravity by providing comic relief, all in an attempt to mask his own pain. We relate to the characters in Samurai because we already know them–we have seen them before in innumerable iterations. These archetypes do not make Kurosawa’s work unoriginal; but instead, they make it sublimely human.

The Shakespearean parallels do not end with the characters. The final battle (or “showdown” to use vernacular from the American Western genre) is reminiscent of the Battle of Agincourt in Act IV of Shakespeare’s Henry V. The extended title of the film could arguably be Seven Samurai: we few, we happy few, we band of brothers. We the audience are rooting for the underdogs, who are woefully outnumbered. Despite the odds, our heroes triumph over their enemies–but the victory comes at a heavy price. The final scene is downright Shakespearean in and of itself. “In the end, we’ve lost this battle too,” says one of the surviving samurai. “The victory belongs to those peasants, not to us.” The village will endure, and perhaps even thrive now that the threat is gone, but the samurai must return to their own dispossessed lives and try to make their way in the world.

Throughout his career, Kurosawa was a great admirer of director John Ford; as a result, he was influenced by American Westerns of the 1930s and 1940s. In turn, Kurosawa’s influence on John Ford is evident in Ford’s 1956 film The Searchers. While it is not unusual to see artists inspiring artists, it is rare to see an artist inspire an entire genre; three of Kurosawa’s films were remade, as westerns, in the U.S. The story structure of Seven Samurai fits neatly into an American Western film–it was remade (or rather retold) in the form of The Magnificent Seven (1960).

If you have never seen Seven Samurai, I highly recommend that you do so. The remake of The Magnificent Seven is being released this weekend. If you go see it, know that you ultimately have Kurosawa to thank for that particular 2 hours and 12 minutes of movie entertainment–and then go watch his movie.