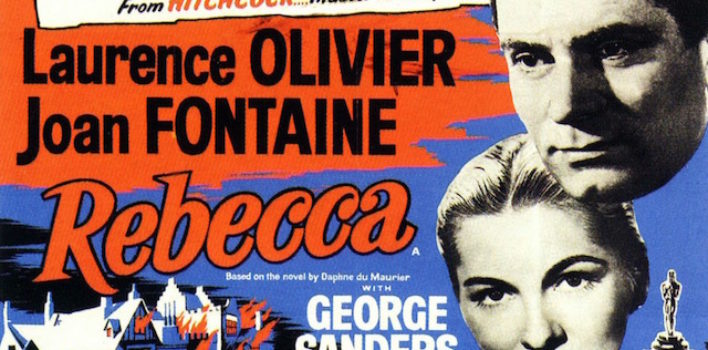

Reviewing the Classics| Rebecca

I am quite surprised to be the first to review a Hitchcock film here on Reviewing the Classics, but I am sure I won’t be the last. While most people think of Psycho, The Birds, or North By Northwest first when they think of Hitchcock, I’ve always been attracted to his quieter films, a little off the beaten blockbuster path.

I am quite surprised to be the first to review a Hitchcock film here on Reviewing the Classics, but I am sure I won’t be the last. While most people think of Psycho, The Birds, or North By Northwest first when they think of Hitchcock, I’ve always been attracted to his quieter films, a little off the beaten blockbuster path.

Rebecca is based on a novel of the same name by Daphne du Maurier published only two years before the film’s release. Though penned in the post-Gothic era, the story is very Gothic in mood and tone. The thrills and chills are purely psychological, and this is what makes the story so enthralling. Hitchcock’s films Jamaica Inn and The Birds were also based on du Maurier’s works.

In a nutshell, Rebecca follows the story of a remarkably average young woman working as paid companion to rich and terrible American during her stay in Monte Carlo. This chief character actually has no name in the book, she is simply referred to as the second Mrs. de Winter after she is swept away in a whirlwind romance with the wealthy English widower, Maxim de Winter. After a brief courtship, they are married and return home to his Cornish estate called Manderley.

After a day or so in her new home, Mrs. de Winter realizes the frightening situation she’s landed herself in. Everyone seems to have loved the first Mrs. de Winter, Rebecca, so there is a sense of constant comparison. Additionally, the circumstances of her death are mysterious, which leaves a general unease throughout until the climax. These two aspects combined create an immense tension for our new lady de Winter, and as the story progresses, Rebecca’s ghostly presence becomes even more powerful than if she were there herself in person.

This heavy presence is only perpetuated by the housekeeper, Mrs. Danvers, who especially loved her “mistress” most of all. She makes for an eerily subtle villain, who tortures the new Mrs. de Winter with Rebecca’s presence as if she herself feels the duty to execute the dead woman’s jealousy. Mrs. Danvers is evidently in love with Rebecca, and there is a lot of unsettling sexual undertone throughout the story. One scene in particular that reveals this is that in which Mrs. Danvers leads Mrs. de Winter into Rebecca’s old room and shows her some of her things, including her lingerie. She admires the lingerie, caresses it even, and all to cause both unrest in Mrs. de Winter, as well as some bizarre sexual satisfaction for herself.

Hitchcock took an even darker turn with Mrs. Danvers than the novel did. He played her off colder and crueler in the psychological torment of our heroine. This is very typical Hitchcock and, I think, makes the movie version of the story more watchable and compelling. I remember watching this movie with a friend and how uneasy it made her just by experiencing these scenes of elusive but intense abuse.

Along with the presence of the ghost, is the all the self-doubt and self-deprecation that comes with living in someone else’s shadow. Mrs. de Winter is young, slightly awkward and clumsy, but lovable. Rebecca is painted as a caricature of class, beauty, and sophistication. It’s a classic situation of being the “other woman,” the one who comes next, and feeling you are never good enough. Maxim never implies this himself, but everyone else, Mrs. Danvers, and even the heroine herself make her feel inadequate.

In the famous ballroom scene, Mrs. Danvers tricks Mrs. de Winter into wearing one of Rebecca’s old gowns. This makes Maxim very angry, thinking that his new wife did it of her own volition. This conflict sends Mrs. Danvers into a delicious state of control and victory. She comes to Mrs. de Winter in her tears and brokenness only to taunt her further, even encourage that she commit suicide and be done with it. Mrs. Danvers’ sinister speech to her is haunting, and delivered in an almost hypnotic tone,

“Why don’t you go? Why don’t you leave Manderley? He doesn’t need you… he’s got his memories. He doesn’t love you, he wants to be alone again with her. You’ve nothing to stay for. You’ve nothing to live for really, have you?”

There is some debate about Maxim having an abusive nature. While I would agree he is psychologically and emotionally unstable, ultimately unfit to be a husband, I would not agree that he is malevolently abusive by intent. He is, however, a murderer.

This is one of the chief changes from book to screen. When he confesses to his new wife that he killed Rebecca it is quite a shock. Not that he should get away with murder, but Rebecca was no helpless, innocent damsel. She cheated on her husband repeatedly, and out of spite. She was a partier and a player and even admitted she enjoyed the idea of ruining this man’s life.

This is one of the chief changes from book to screen. When he confesses to his new wife that he killed Rebecca it is quite a shock. Not that he should get away with murder, but Rebecca was no helpless, innocent damsel. She cheated on her husband repeatedly, and out of spite. She was a partier and a player and even admitted she enjoyed the idea of ruining this man’s life.

In the novel, Maxim confronts Rebecca about her subsidiary relationships, and she offers him only malicious responses. He is enflamed by her attitude as she boasts about being pregnant by another man and passing that baby off as his heir. We later find out this is untrue, but in his rage, he shoots her with a pistol. When he shoots her, blood spills everywhere and Rebecca simply laughs. It is the chilling laughter amidst her own violent demise that is enough to reveal to the audience, and the world, who she really is.

Hitchcock struggled quite a bit with executing the ending. The MPAA felt this death was too violent and did not like the hero of the story to be portrayed as a murderer, so they altered it in their censorship. Maxim and Rebecca have their confrontation, but it includes a physical altercation which causes him to accidentally push her. She hits her head and dies.

There really isn’t hope for a happy ending, though, even with the change in death. Too much has happened; too much has been compromised and destroyed. After such mental and emotional turmoil, it is impossible to pick up where they left off. Though the film plays it off like they can, it seems even the characters themselves know better…

“I can’t forget what it’s done to you. I’ve been thinking of nothing else since it happened. It’s gone forever, that funny young, lost look I loved won’t ever come back. I killed that when I told you about Rebecca. It’s gone. In a few hours, you’ve grown so much older.” ~Maxim de Winter

Rebecca as both novel and film still remains a conversation sparker to this day. I would say it is the story that lit the flames for the era of film noir, and set the precedence for such successful contemporary thrillers as Gone Girl, and The Girl on the Train, both of which have similar characters and themes as Rebecca. It is a tale that will wreak anxiety and make you cringe, achieving the great goal and purpose of the suspense thriller genre.