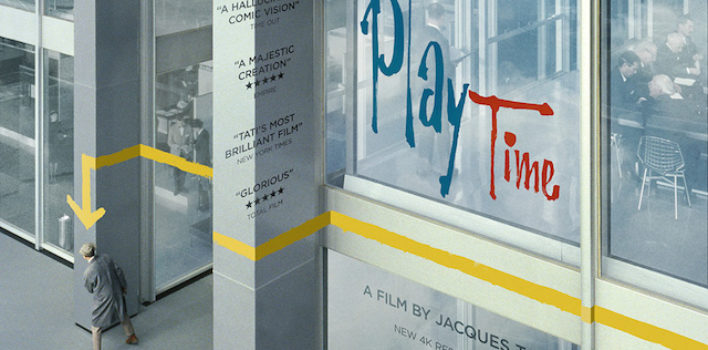

Reviewing the Classics| Playtime

Long before the onslaught of films chastising us for The Way We Live Now – including themes such as technophobia, interpersonal miscommunication, and the daunting rise of urbanity – that has marked the better part of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, director Jacques Tati developed a rather clever and innovative take on encroaching modernity with his opus Playtime back in 1967. Famous for continuing the exploits of his beloved character M. Hulot and for nearly bankrupting its studio by constructing the entirety of its enormous Parisian sets, Tati’s film stands at the intersection of traditionalism and rapid societal “progress” that the director argues has drastically altered the way we live now.

Long before the onslaught of films chastising us for The Way We Live Now – including themes such as technophobia, interpersonal miscommunication, and the daunting rise of urbanity – that has marked the better part of the late-twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, director Jacques Tati developed a rather clever and innovative take on encroaching modernity with his opus Playtime back in 1967. Famous for continuing the exploits of his beloved character M. Hulot and for nearly bankrupting its studio by constructing the entirety of its enormous Parisian sets, Tati’s film stands at the intersection of traditionalism and rapid societal “progress” that the director argues has drastically altered the way we live now.

Instead of getting bogged down with the weight of such paramount implications, Tati cushions his critique with the humor of physical comedy and the sheer ridiculousness of the film’s set-up. The filmmaker eschews any semblance of a plot or character study in favor of simple vignettes that follow a large cast of characters – though none intentionally well defined – as they move about the homogeneous constructs of this alien-looking Paris. At the center is Tati himself as the bewildered M. Hulot who acts as our guide on this tour of utter confusion.

Through expertly choreographed sequences, Tati takes his audience from the international airport to a monolithic office building downtown hosting an expo to an apartment complex and finally to an unfinished nightclub. Chaos reigns in the interactions of these clueless characters – M. Hulot chasing the elusive M. Giffard through a labyrinth of cubicles, a disgruntled tour guide herds a group of chatty American tourists around like sheep through the various set pieces, the inept staff at a restaurant scurries around the establishment as its brand new architecture crumbles all around them – and yet it’s only the illusion of chaos. Tati is the master of staging with no step out of place and every tumble coordinated perfectly and intentionally.

Tati uses this supreme control to accentuate his overall theme. In constructing this sleek, yet sterile version of Paris completely from scratch, he ensures the fulfillment of his creative vision. Space is used effectively and carefully throughout; there are no close-ups in the entire film, and the enormous frame (filmed on 70mm) is full of characters and goings-on throughout. There is so much happening in any given frame of Playtime that it most certainly demands repeat viewings to take it all in. Tati perfects the art of misdirection by allowing multiple interactions to transpire onscreen at all times and relying on overlapping and oftentimes barely intelligible dialogue to explain his characters’ actions. All of this adds to the idea that the modern world often makes no room for subtlety or quiet contemplation.

Throughout Tati posits technological innovation and the hurried pace of urbanity as an obstruction to natural human communication. This he captures hilariously with exaggerated sound effects (the squishy chairs, echoing footsteps, the buzz of neon lights) and a comical skepticism toward the progress of convenience (a broom affixed with headlights receives “oo’s” and “ah’s” from onlookers, constantly malfunctioning intercoms and other devices, the unintentional inconvenience of streamlined transportation). In one effective scene, Tati’s camera remains outside a modern-looking apartment complex positioning his audience as onlookers. We see the interiors of two identical units through the enormous glass windows, and both sets of inhabitants have switched on their TV sets. The camera is angled in such a way that either side appears to be reacting to their neighbors rather than what happens on the screen. It’s a bitingly clever take on how technology has infiltrated and significantly altered the once-sacred space of the home.

Throughout Tati posits technological innovation and the hurried pace of urbanity as an obstruction to natural human communication. This he captures hilariously with exaggerated sound effects (the squishy chairs, echoing footsteps, the buzz of neon lights) and a comical skepticism toward the progress of convenience (a broom affixed with headlights receives “oo’s” and “ah’s” from onlookers, constantly malfunctioning intercoms and other devices, the unintentional inconvenience of streamlined transportation). In one effective scene, Tati’s camera remains outside a modern-looking apartment complex positioning his audience as onlookers. We see the interiors of two identical units through the enormous glass windows, and both sets of inhabitants have switched on their TV sets. The camera is angled in such a way that either side appears to be reacting to their neighbors rather than what happens on the screen. It’s a bitingly clever take on how technology has infiltrated and significantly altered the once-sacred space of the home.

In all of this, Tati avoids outright cynicism by suggesting an alternative instead of wallowing in the inevitability of an increasingly manufactured world. If M. Hulot fumbles around never quite making sense of this confounding new age, Tati gives a glimmer of hope in Barbara (Barbara Dennek) the young American tourist. She already stands out amongst her group as the youngest by quite a bit, but she also makes no apologies in following her own impulses even if that requires deviating from the norm – she often wanders from the group, attempts to photograph the mundane, wears an eye-catching emerald dress amidst a sea of contemporary blacks and grays. Nonconformity, Tati argues, may be the only thing that can inject life into this lifeless urban environment. He suggests as much near film’s end when the patrons of the nightclub begin to let go of their societal inhibitions and embrace imperfection as the tenets of modernity crumble – the restaurant’s architecture proves its infrastructure cannot support the façade of its alluring style.

Lest anyone lose hope and accept the world of Playtime as the new norm, Tati slyly reminds us throughout the vestiges of the old world remain within arm’s reach. Despite the presence of these new, technologically advanced buildings standing erect in a perfectly shaped grid, iconic monuments of Paris’ history are reflected in the sleek glass windows in several different shots. The past is not lost, and the more individuals resist conformity like M. Hulot or Barbara, the more colorful and delightfully messy our future will be. Playtime may have been released at the advent of mid-twentieth century advancement, but it’s perhaps more relevant now than ever. In the post-techno age of social media and information saturation, we’re now more connected than ever, but face similar threats of homogeny as we become increasingly dependent on personal devices. Of course, Tati was likely no extreme Luddite, and thus, Playtime shouldn’t be read as a complete disavowal of technology or progress. Likewise, if he were still alive today, I don’t think he’d decry the use of mobile phones or Facebook, but the hilarious breakdown at the nightclub and the guests’ accept thereof suggests it doesn’t hurt to let our guard down every once in a while either.