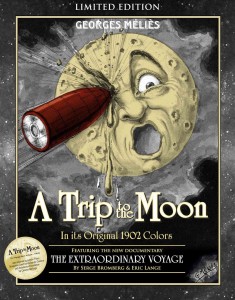

Reviewing the Classics| A Trip To The Moon

The science fiction imagination has changed drastically over its long life. From it’s beginnings in the 17th century with Johannes Kepler’s Somnium, a work regarded by many as the first science fiction novel, the genre has evolved as both scientific and cinematic technology improved. Stories once considered to be speculative science fiction based on current scientific data have since shifted to being considered science fantasy.

The science fiction imagination has changed drastically over its long life. From it’s beginnings in the 17th century with Johannes Kepler’s Somnium, a work regarded by many as the first science fiction novel, the genre has evolved as both scientific and cinematic technology improved. Stories once considered to be speculative science fiction based on current scientific data have since shifted to being considered science fantasy.

The early 20th works of Georges Méliès might fall into this category now, but in his heyday, more than a century ago, Méliès was a pioneer. He is hailed as the first cinematic auteurs, widely regarded in film history as the father of special effects and film editing, and bestowed the title of the world’s first “Cinemagician.” In addition to all of these illustrious seminal designations, including being credited with the first horror film,1896’s The Haunted Castle, Méliès is also credited with birthing science fiction as a film genre with his 1902 silent film, A Trip to the Moon (Le Voyage dans la Lune).

Based narratively on H.G. Well’s The First Men in the Moon and Jules Verne’s From the Earth to the Moon and Around the Moon, the 13-minute short film follows Professor Barbenfouillis (Georges Méliès) and his Astronomic Club. He proposes a daring lunar adventure by making a giant cannon to blast him and five companions to be the first scientists to explore the moon. After dealing with some flak from arch-nemesis, the wizard Parafaragaramus, the explorers and Barbenfouillis embark to the rooftops of Paris where their giant cannon has been constructed. Once ceremoniously sent off with plenty of “sailorettes”, trumpeting fanfare, and some guy waving a sword, the six companions are shot to the moon and iconically land in the eye of the Man on the Moon.

After exiting the capsule/bullet they were blasted in, our intrepid explorers watch the earth from afar, nap amidst the stars, experience a lunar snowstorm, and take solace in a subterranean cave. Amidst the moony stalagmites and after turning umbrellas into mushrooms (I still haven’t figured out the meaning of that one), they meet the strange lunar inhabitants, the Selenites. They are taken captive, only to escape, and beat a hasty retreat to their capsule back to earth, but not before a Selenite tags along for the ride. They return to Paris to adulation, a hero’s welcome, a statue, and a captive Selenite to boot!

Clearly the stuff of fantasy nowadays, since we know what comprises the moon and it disappointingly lacks bug-like, skeletal moon creatures. However, we must put ourselves in the audience when this narrative was first introduced. For decades, the popular imagination of Méliès’ audience had been stirred by the massively popular novelist Jules Verne, a heavy influence on this film. The concept of an alien race living on the moon, also being shot to the moon, walking on it, and breathing the atmosphere, not only seemed feasible, but popularly accepted speculation. If you think this outlandish; ask a bunch of people how feasible it is that space exploration could one day be as true as it is portrayed in Interstellar. The popular mythical narrative of the moon in the late 19th and early 20th century is similar to our current narrative of the vast expanse of space. Like good Sci-Fi of today, Méliès created the first cinematic stories that reflected the hopes, fears, and aspirations of its people.

Clearly the stuff of fantasy nowadays, since we know what comprises the moon and it disappointingly lacks bug-like, skeletal moon creatures. However, we must put ourselves in the audience when this narrative was first introduced. For decades, the popular imagination of Méliès’ audience had been stirred by the massively popular novelist Jules Verne, a heavy influence on this film. The concept of an alien race living on the moon, also being shot to the moon, walking on it, and breathing the atmosphere, not only seemed feasible, but popularly accepted speculation. If you think this outlandish; ask a bunch of people how feasible it is that space exploration could one day be as true as it is portrayed in Interstellar. The popular mythical narrative of the moon in the late 19th and early 20th century is similar to our current narrative of the vast expanse of space. Like good Sci-Fi of today, Méliès created the first cinematic stories that reflected the hopes, fears, and aspirations of its people.

And like any great science fiction story, its meaning went well beyond its 12-minutes of narrative. The characters within this story are highly exaggerated characters, bouncing around and wearing astronomer outfits befitting of Arthurian wizards, and seem slightly buffoonish in their actions once on the moon. Many scholars of the film have ventured that Méliès’ intention was a portrayal of the arrogance and pretension of 19th century scientists.

I think it best to clarify, given previous statements on mythical narrative, that certainly the vast majority of people did not actually believe you could shoot men to the moon in a cannon or fall off the moon’s cliff and plummet back to Earth. However, there was a certain amount of pataphysical elements (the science of imaginary solutions) allowing for curious speculation combined with absurdity to make a broader point to Méliès’ audience. It was a mashup, to use a modern term, of the fantastic and the scientific to satirize the scientific community and still inspire wonder for the yet to be explored lunar surface.

The wonder Méliès concocted did not come from detailed verbal storytelling, but from the special effects, film tricks and edits he had developed in previous works. Méliès had developed the first instances of cutting and splicing that would come to be known as narrative filmmaking. By accident, he had discovered that the human brain has built in shortcuts for detecting motion, called visual persistence. Because Méliès began quick, tight edits for his films, he was able to tell a story in a visually pleasing and fluid manner. Movies were no longer one consistent long shot, but could be edited into something that had more in common with a novel than with previous iterations of film.

This same type of meticulous and artistic editing is visible in the many special effects he employed. When Professor Barbenfouillis battles the Selenites on the moon’s surface, he smashes them with his umbrella and they are vanquished in a puff of smoke. A delightful visual and story gimmick achieved by a stop trick technique known as substitution splicing; where the camera would stop rolling long enough for something to be moved, put it, or taken out. Méliès meticulously spliced (hence the name) the shots into one cohesive take that gave these effects a magical feel; like the puffs of smoke or the previously mentioned umbrella into a mushroom.

This same type of meticulous and artistic editing is visible in the many special effects he employed. When Professor Barbenfouillis battles the Selenites on the moon’s surface, he smashes them with his umbrella and they are vanquished in a puff of smoke. A delightful visual and story gimmick achieved by a stop trick technique known as substitution splicing; where the camera would stop rolling long enough for something to be moved, put it, or taken out. Méliès meticulously spliced (hence the name) the shots into one cohesive take that gave these effects a magical feel; like the puffs of smoke or the previously mentioned umbrella into a mushroom.

Other effects were created using pulleys, smoke machines, stage machinery, and pyrotechnics. It all works together with imaginative and beautifully rendered production design to create what can only be described as a moving painting. Since the movie is always framed within the same set design, the people move as if they are moving across pages of a pop-up book and we as the audience are pulling the tabs to move the background machinations.

Subject of many books, research, and film classes, Georges Méliès most well-known film will live on in our collective memories for its whimsical shot of the Man on the Moon and groundbreaking work in special effects. Obviously, the proof is in the pudding, so to speak, and reviewing a movie that is now over 110 years old is a testament in itself to the genius and significance of A Trip to the Moon. One can only hope its preservation will endure and influence stretch to the moon and back.

*A note about versions. This movie is available on Netflix in a black and white version, as well as a restored, hand-painted color version. Both have merits, but I prefer the hand-painted, color version with an updated soundtrack by French band, Air, that showed at the 2010 Cannes Film Festival.

How funny! I just sent you my blurb about “Caligari” and here I find more silent movie awesomeness. 🙂 I love Georges Méliès. His vision was far ahead of his time and so imaginative. Thank you for sharing this!

Welcome to the new series Josh and Joel are starting 🙂

Um, awesome! 😀

Yes, you are in for many more wonderful reviews of super old movies. Joel and I are going to try and stick to movies from pre-Golden Age Hollywood, though Chaplin’s films bleed into that time period. Should be awesome!

Pingback: Netflix Your Weekend July 2.0 | Reel World Theology