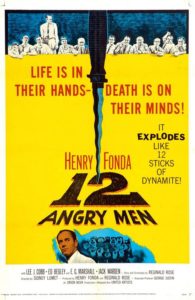

Reviewing The Classics| 12 Angry Men

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the 1957 film 12 Angry Men, and it is as relevant and captivating as ever. Our current cultural climate is different and much more progressive than the 1950s, but we still face the same issues of racism, disparaging of immigrants, and general prejudice and distrust of others. It’s such a timeless film for those reasons that it could never be remade again and it would still stand strong on a philosophical and ethical foundation.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the 1957 film 12 Angry Men, and it is as relevant and captivating as ever. Our current cultural climate is different and much more progressive than the 1950s, but we still face the same issues of racism, disparaging of immigrants, and general prejudice and distrust of others. It’s such a timeless film for those reasons that it could never be remade again and it would still stand strong on a philosophical and ethical foundation.

The film is as minimalist as it gets, but cleverly so. Based on the play by Reginald Rose, it is a classic example of the importance of script and great performers to execute it. So many big budget films, even with their extravagant production design and abundance of special effects, have failed to do what this film does simply because it places prominence on the aspects that matter most in quality. The tension is derived dialogue and body language in place of action, and what the characters don’t say is just as important as what they do.

Though the cast is strictly male, it is quite an eclectic mix of men, even though the characters have no names, only jury numbers to tell them apart. In truth, you almost forget they don’t have names because they are so rich with personality. I admit even as I pulled up IMDB to get some specifics to write this article, I expected to see character names, forgetting completely that they never had any. Each of the actors expertly reveals unique points-of-view, mannerisms, and carriage that make their character stand out from the others.

Director Sidney Lumet utilizes clever camera technique to make a one-room setting more engaging and intense. At the start of the film, we get an unbroken shot for a few minutes and the camera angle begins overhead to demonstrate a distance between the characters. As the film goes on, the angle is brought down to eye-level and some extreme close-ups also take place. When the film is over and the characters go their separate ways, the camera takes a step back to wide shots again.

The camera isn’t the only object used to make the 16×4 foot jury room a more thrilling set. The director and actors actually sat in there, rehearsing lines over and over prior to filming to really stir up the sense of claustrophobia and heightened tempers. This is probably why the cast has such a volatile dynamic that feels natural. This is amplified by the point made in the first few minutes of it being the hottest day of the year and the tempers in the room being equally as hot. As an Arizona native, I know all too well what the sweltering, stifling heat does to people. Irritability skyrockets and people are more apt to say what they want, whether or not it’s useful or kind. If there were driving in this film, we’d see road rage instead. It’s the same concept.

Henry Fonda (also a producer of the film) initially comes across as the star, the first man to really question the case and long to dig deeper for the truth, but I think this movie really belongs to Juror #3 played by Lee J. Cobb. Cobb has been in countless films, including another Oscar contender (and one of my favorites of all time) just three years prior, On the Waterfront. Cobb is a scene-stealing, vigorous performer and easily the angriest of the twelve. I feel like the story arc rests on him wrestling with his own demons. In the beginning, he states that he doesn’t have any personal feelings about the case, he’s only interested in facts. Even as he says that we kind of know it’s a yarn, but we aren’t sure why yet. Layer by layer gets peeled away as we learn about him and his tumultuous relationship with his son. It’s obvious he’s hurting deeply, but it’s not as obvious to his fellow jurors as it is to the viewers. I think that makes the build-up to his ultimate breakdown even more intense.

My only criticism of the film is that, while it explores controversial subjects that need exploring, it falls short with one. The one thing perhaps even more scandalous than prejudice at the time would have been male emotions and vulnerability. The 1950s were a pinnacle of machismo. Emotions and mental health were completely taboo subjects for most families, but especially for boys and young men who were encouraged to be emotionally constipated. Even Cobb’s character reiterates this when he tells a fellow juror he saw his son run away from a fight and he was so embarrassed he almost threw up. While the characters do have emotional reactions, they weren’t as deeply delved into and unpacked as I would have wished because of the time period. They had no problem showing men in rage, that was commonly known as something men just do, but especially with Juror #3, I would have liked to see more of the grief and regret, not just the rage. I don’t think this film needs to be remade at all, but if it were, I would add more about the “whys” behind the emotional dynamic.

12 Angry Men is one of the few classic films that has an enduring appeal to most people, even those who don’t like older cinema. If you are one of those people, this is a film I implore you to give a chance. Though our judicial system is flawed, like any human system, I think this story is more hopeful than not. It begins roughly, with a bunch of guys wanting to “get it over with” and move on with life, but all it takes is one voice to speak up and get the ball rolling by asking questions and thinking critically. Ultimately, 12 Angry Men is a shining example of the potential for both evidence-based conclusions and compassion under the law that will restore your faith in humanity in a way that doesn’t sugarcoat the truth, but rather reveals the determination it takes to obtain it.

“12 Angry Men” is my favorite film, and I’m happy to see that someone remembered this anniversary. The racial prejudice angle is often overemphasized when discussing this film. Actually only one of the jurors shows racial animus against the accused – that’s Juror no. 10, played by Ed Begley – and he is roundly shunned by the other jurors. I do wonder on what basis the author claims that “emotions and mental health were taboo for most families” in the 1950s. Is there any historical evidence for this, or is it just a cliché of the period? As for the Cobb character showing grief and regret – well, I think he shows plenty of that in his final break down in the final moments of the film, where he tears up the picture of his son and changes his vote to “not guilty.”

Hi Michael, thank you for your comment!

To answer your question, I do not have peer reviewed evidence regarding my statement. (Though I work in a library so I am sure I could find some!) I’m basing it more on personal experience of others who lived in the time period, as well as just the general cliche, as you say. Psychology was widely seen as woo-woo pseudoscience, and any discussion of emotion on a critical thinking level was hardly done, and if it was, it was often written of as “women’s talk.” My dad and I kind of coined the phrase the “under rug swept generation,” and even my grandmother admitted out loud once, “there’s certain things we just don’t talk about.” So more what I meant was the time period does have an effect on how open and vulnerable the characters are, especially men, and especially men from a hard city. All of those things play a factor. There’s certainly a lot of machismo being thrown around the room, such as Cobb’s comment about how embarrassed he was about his son getting bullied.

Additionally, I totally agree about Cobb showing grief and regret at the end of the film, but I felt that there certainly could have been more of that throughout. It’s just my own personal preference. I like things to really dig in deep if possible, but I know that a lot of classic films didn’t do that because of the culture of the time as previously discussed. These days we are totally the opposite in culture. People blurt out their emotions and opinions in a deluge without a filter, and I think this far swinging the other way is a direct result of years of emotional oppression and sweeping things under the rug as a society. This is only my observation of course as I survey trends and entertainment over the past century. I wholly admit I could be wrong.

Again, thanks for commenting and sorry it took me so long to see this! 🙂