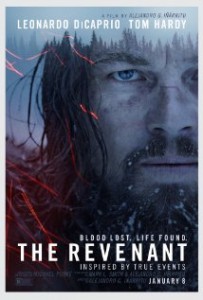

Review| The Revenant

The Revenant, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s followup to his critically acclaimed Birdman (2014), was one of the most talked about films of the past year. It was on numerous “Most Anticipated Movies of 2015” lists, and if you follow movie news all, you know of the plethora of difficulties entailed in creating this film: it was shot using natural light (which is terribly hard to do), and Leonardo DiCaprio ate real buffalo liver, and so on and so forth. Nevertheless, in spite of all the painstaking attempts to create a powerful sense of verisimilitude, Iñárritu’s film is little more than banally beautiful Oscar bait.

The Revenant, Alejandro González Iñárritu’s followup to his critically acclaimed Birdman (2014), was one of the most talked about films of the past year. It was on numerous “Most Anticipated Movies of 2015” lists, and if you follow movie news all, you know of the plethora of difficulties entailed in creating this film: it was shot using natural light (which is terribly hard to do), and Leonardo DiCaprio ate real buffalo liver, and so on and so forth. Nevertheless, in spite of all the painstaking attempts to create a powerful sense of verisimilitude, Iñárritu’s film is little more than banally beautiful Oscar bait.

Based on a true story (aren’t all movies these days), The Revenant is centered upon tracker Hugh Glass (DiCaprio), who is attacked by a bear in an extremely overrated scene (see Backcountry for the gold standard of bear mauling movie moments), forced to watch his son be murdered by the evil John Fitzgerald (Tom Hardy), and abandoned by his hunting party. Needless to say, Glass is particularly unhappy about the last two occurrences, and so he sets out on a revenge mission, facing death-defying odds along the way.

Prior to discussing some of the film’s shortcomings it is important to note that The Revenant is a beautiful film—a movie that, if you are interested in seeing at all, needs to be viewed on the big screen. Iñárritu has created some wonderful, if a bit overused, long takes. Also, the film boasts one of the greatest living cinematographers in Emmanuel Lubezki, and his compositions are just breathtaking. Additionally, DiCaprio, Hardy, and Domhnall Gleeson turn in some stellar performances. Ultimately, however, a good film should do more than simply look stunning and show of its cast members’ undeniable talent, and that is precisely where The Revenant comes up short.

One of the more troubling aspects of the film is that while it is ostensibly a tale of unbridled naturalism, the linear narrative is interwoven with sequences of abstract spiritual discovery and revelation. These visions/meditations/dreams clash tonally with the dispassionate gaze of the camera and  serve as an unwarranted distraction. At times, it feels like Iñárritu is trying to do his best Terrence Malick impression; it is an attempt which fails miserably. It would have been much more preferable to let the film’s resurrection imagery—most of which was already very on the nose—serve as subtext, but by making the implicit explicit, Iñárritu delivers on a silver platter what little mystery the film contains.

serve as an unwarranted distraction. At times, it feels like Iñárritu is trying to do his best Terrence Malick impression; it is an attempt which fails miserably. It would have been much more preferable to let the film’s resurrection imagery—most of which was already very on the nose—serve as subtext, but by making the implicit explicit, Iñárritu delivers on a silver platter what little mystery the film contains.

Moreover, the tonal confusion engendered by the film’s more introspective moments is heightened by the fact that the narrative is populated by so many markedly bland characters. Glass is a stock, one-dimensional protagonist. If we feel any sympathy for or attachment to him it is only because he is human, for he is assuredly not an interesting enough character to hold our attention otherwise. Tom Hardy’s Fitzgerald is essentially a comic book villain, bad to the bone and completely without the interesting motive or likability that makes for a good antagonist (like Kylo Ren). It is not, to be clear, that the actors perform poorly—I have already said the opposite—it is simply that the roles with which they must work are so uninteresting that the fact that they will likely (and rightfully) garner some Best Actor nods out of the ordeal is a powerful testament to their talent.

In the end, perhaps the most interesting thing about The Revenant is the role it plays: It utilizes the aforementioned verisimilitude and Malickesque moments to give audiences the sensation of having enjoyed an artsy film, when, in reality, they have seen a beautiful film (and not much else). But, if you are planning on spending your hard-earned cash on one of the two movies released this past weekend about bad things happening to people in the woods, The Revenant is most certainly your best option. Of course, that may not be saying much, given The Forest is such a pitiful excuse for a film that it is an early frontrunner for the worst movie of 2016. The Revenant is somewhere in between, still lost in the forest.

I must say that I enjoyed the movie more than you did, although I do see that Fitzgerald is a one-dimensional villain. But I can’t help but take issue on the point of the naturalism of the film (in terms of focusing on nature, not the philosophical worldview) and spirituality – that, to me, seemed like an intentional decision on the tonality of the film, being representative of Glass himself. He himself is a settler, which would tie in more with the naturalist side of things. But, as we come to find out, he has lived with the Pawnee people, married one of them, and has a biracial son. So, we may assume, the spiritual has an effect on him. Is it not a mark of good filmmaking that we see not one, but both sides of Glass’s persona represented in the film?

I tend to agree Logan. Blaine is the outlier when it comes to not caring for this film very much. I thought this was one of the better films of the year and the single-mindedness of Hardy’s Fitzgerald struck me as one of the most honest characters I have seen in a film in a long time– or at least since Mad Max.

Pingback: RWT Top 20 Films of 2015: 5-1 | Reel World Theology