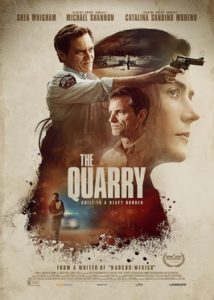

Review| The Quarry

Scott Teems’ new film, The Quarry, strikes upon two of my deepest obsessions: southern gothic literature and music. It doesn’t have the magical realism of True Detective’s first season and it doesn’t have the grotesquery of the characters of Flannery O’Connor’s novels and short stories or John Huston’s adaptation of her novel, Wise Blood. However, it has the existential foreboding of all of those touchpoints along with the music of 16 Horsepower, Slim Cessna’s Auto Club, and the like. Flannery O’Connor described the South as “Christ-haunted” and considering the varied Southern locations that like to claim their place in the increasingly ambiguous borders of “the Bible Belt,” this description still holds sway. It definitely illuminates the darkness inherent in Teems’ The Quarry.

We are introduced to a man (Shea Whigham) who is found near death on the side of the road by a Latino pastor on his way to serving as a pastor of a small town church. As they make their way to the small town, they stop at a quarry just outside of the town. The preacher beckons the man to confess whatever he has done and in a fit of anger, the man murders the pastor and takes his name and place as the pastor of the small church. Enter Chief Moore (Michael Shannon), the law in town, who becomes increasingly suspicious of this odd man who acts like no other pastor that he or his lover, Celia (Catalina Sandino Moreno)—who offers up her home to each pastor—has seen before. As the days go by and the man acts as the pastor of this small church of Latinx members , what takes place is something similar to that found in the annals of Southern Catholic literature: the words of the good book read by someone who hadn’t read it before and is burdened by a heavy guilt begins to change the man and his flock. All leading to a violent climax when he finally confesses to the least of these.

There are no frills to this film. It has more in common with the understated natures of The Three Burials of Marquiades Estrada and The 25th Hour than any other films or shows that follow in its general trajectory. What makes the story and the characters come alive is the brilliant actors chosen to portray the townsfolk of this small town. Shea Whigham shines in this role as we can see the burden of his past actions slowly crushing his soul and spirit, only increased by his murder of the Latino pastor. As he opens himself up to the Bible, first as a cover, he begins to be changed and the existential toll of mercy and forgiveness begins to affect him. His congregants increase as his message of forgiveness and mercy lightens their load and their burdens as well. When asked (through a translator) why he and his message is so different from past pastors, he responds simply and humbly with the fact that he is only reading the words. It takes a criminal to remove the human ego from the transmission of the gospel to the people. It takes the convicted and burdened to know the essential goodness of the Word.

The man becomes more and more conflicted as his identity begins to veer into a true man of God, but as this identity shifts, there is one thing that keeps him from a full transition, the thing the Mexican pastor told him in the first place: confession leads to freedom. As long as the man continues to avoid confession, the more innocents he begins to harm in the process and the law continues to bear down on him. The climax is only satisfying to those who are on the film’s existential level. The man does achieve a form of freedom through confession, but it comes at a great cost. This film is deeply Christ-haunted. The Law and Gospel saturates the borders of this small town and each character ends up dying by the sword of the Law or receiving mercy through the grace of Christ. I deeply appreciate these kinds of stories being put to film because they are honest, but not simple. Just like the good book.

The man becomes more and more conflicted as his identity begins to veer into a true man of God, but as this identity shifts, there is one thing that keeps him from a full transition, the thing the Mexican pastor told him in the first place: confession leads to freedom. As long as the man continues to avoid confession, the more innocents he begins to harm in the process and the law continues to bear down on him. The climax is only satisfying to those who are on the film’s existential level. The man does achieve a form of freedom through confession, but it comes at a great cost. This film is deeply Christ-haunted. The Law and Gospel saturates the borders of this small town and each character ends up dying by the sword of the Law or receiving mercy through the grace of Christ. I deeply appreciate these kinds of stories being put to film because they are honest, but not simple. Just like the good book.