Review| The Missed Connections of Certain Women

“Did you just see the movie that just got out? Certain Women?” My friend Adam and I had barely cleared the threshold of the Landmark Theater in Highland Park, Illinois, my first experience at the art/indie cinema franchise, when an older couple, walking out into the brisk, fall air of Chicago’s northern lakeshore, asked this question. We stopped and affirmed we had and they followed up with another query. “Do you know what the movie was all about? Did we miss something, because all I know is I shouldn’t move to Montana,” said the older gentlemen over his wide-rimmed spectacles.

“Did you just see the movie that just got out? Certain Women?” My friend Adam and I had barely cleared the threshold of the Landmark Theater in Highland Park, Illinois, my first experience at the art/indie cinema franchise, when an older couple, walking out into the brisk, fall air of Chicago’s northern lakeshore, asked this question. We stopped and affirmed we had and they followed up with another query. “Do you know what the movie was all about? Did we miss something, because all I know is I shouldn’t move to Montana,” said the older gentlemen over his wide-rimmed spectacles.

How could I blame him? Kelly Reichardt, director of Certain Women, may be one of the few true independent directors left in cinema. Eschewing the normal conventions movie-going audiences have come to expect in laying out a narrative structure and thematics, Reichardt’s cinematic language can be an obfuscation to understanding for the casual audience and even the keenest critic. Hardly a critique, Reichardt deserves high praise for being one o the few director’s willing to be patient enough in developing characters and building themes through sparse, meaningful dialogue and careful composition woven within a tapestry of gorgeous camera work by cinematographer and frequent collaborator Christopher Blauvelt. And having ventured to the mountainous, grassy wilds of Montana, Reichardt and Blauvelt certainly chose a stunning and fitting landscape to spin three poetic narrative strands focusing on four different women’s missed connections and relational isolation.

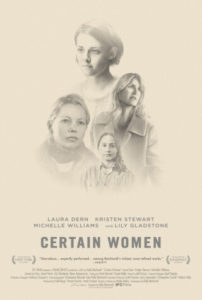

Told in three separate vignettes adapted from a 2009 collection of short stories by Montana native Maile Meloy, Certain Women stars Laura Dern as frustrated, downtrodden lawyer, Laura, who is thrust into a hostage negotiation situation by a nettlesome client in the first section. In the middle vignette, Michelle Williams, frequently called upon by Reichardt to star in her films, plays a skilled, driven business owner woman fraught with relational troubles between herself and her family, who is intent on acquiring local-sourced sandstone from a family friend. The last story stars Lily Gladstone as a ranch hand happening to stumble upon a night class teaching school law, which she knows nothing about and has no interest in, taught by a novice, and frumpily dressed lawyer, Beth, played, in a delightful twist, by Kristen Stewart.

The largest portion of the narrative is given to Stewart and Gladstone’s story. It remains unclear if this was the decision from production but if it wasn’t, Gladstone and Stewart’s performances are tremendous enough to take the lion’s share. In particular, Gladstone’s gawky, smitten Jamie is the standout performance in the movie. True to the muted tones of Reichardt’s direction, Gladstone uses longing, goofy grins and slightly pained expressions to communicate her longing for Stewart’s Beth and to show her own loneliness and isolation as a routine-bound rancher. For her, Beth’s night class is about as exciting as life gets. And while we are unsure if Jamie’s longings for Beth are romantically motivated or out of a desire for friendship with a real human, their moments on-screen together capture one woman’s longing and the others’ disdain for her inferior post teaching school law four hours from civilization and obliviousness to the others’ kindness and rapt attention.

Dern’s Laura and Michelle Williams’ Gina both connect to Jamie and Beth’s story by their similarity of shared missed connections. Laura is a reluctant advocate for a client who desperately longs for restitution in the face of injustice. Gina is singularly focused on obtaining her sandstone at the expense of her relationships with her husband, her daughter, and Albert, the lonely family friend who owns the sandstone. Their paths cross in a much more scandalous and subtle way, Reichardt taking no time to explicitly link them together, and it brilliantly builds sympathy with the audience for both characters but does not subtract from their own development. Again, it’s Reichardt slowly building, block after block, to a satisfying reprise of each vignette to conclude the final 10-15 minutes.

Dern’s Laura and Michelle Williams’ Gina both connect to Jamie and Beth’s story by their similarity of shared missed connections. Laura is a reluctant advocate for a client who desperately longs for restitution in the face of injustice. Gina is singularly focused on obtaining her sandstone at the expense of her relationships with her husband, her daughter, and Albert, the lonely family friend who owns the sandstone. Their paths cross in a much more scandalous and subtle way, Reichardt taking no time to explicitly link them together, and it brilliantly builds sympathy with the audience for both characters but does not subtract from their own development. Again, it’s Reichardt slowly building, block after block, to a satisfying reprise of each vignette to conclude the final 10-15 minutes.

It is in these final moments when patience and thoughtfulness are virtues for both the movie’s audience and its filmmaker. Towards the end, all the female leads are let in a state of self-imposed isolation, wanting and longing all the same for the relational connections either missed or spurned. The film’s final conclusion is one of desperate longing for connection, but also of self-imposed loneliness when those connections are either forsaken or overlooked because of a more selfish, tantalizing predilection. It’s a much more damning, yet subtle, indictment of the human heart’s tendency to live out the negative consequences of the adage, “the grass is always greener on the other side.” Of course, Montana is a literal counter-balance to green grass with its fields of yellowed, cold-weather bitten fields. Maybe the older gentleman I met coming out of the Landmark wasn’t too far off the mark.

Yet, I can’t help but think Reichardt’s motives reach much further. There is a subtextual element of these characters longing to serve and love others, but also to receive the same treatment and be loved and connected to others in return. It echoes Jesus’ teaching to “treat others as you want to be treated,” but echoed reciprocally. When we state one of Jesus’ most famous maxims, one usually shared in a negative sense within other religious traditions, we also affirm our desire for others to treat us that way. The saying implies if we want to be loved, we will treat others with love. Reichardt’s film states this within the framework of the narrative but then also affirms if we love, we wish to be loved in return. While we are not always the best at giving love, sometimes, we are also not so good at receiving it and we miss out on connections formed by people reaching out to us. Certain Women dramatizes this very poignantly, patiently, and cinematically.