Review| Steve Jobs: An Incomplete But Emotive Painting

Steve Jobs is an ambitious film, and I admire its ambition. It has a very unique storytelling mechanism, ironically simplified to dissect the intellect and personality of a very complicated man. On some levels, it succeeds brilliantly. But on others, it falls short.

Steve Jobs is an ambitious film, and I admire its ambition. It has a very unique storytelling mechanism, ironically simplified to dissect the intellect and personality of a very complicated man. On some levels, it succeeds brilliantly. But on others, it falls short.

Writer Aaron Sorkin has repeatedly declared that this film is not a photograph, but a painting – with things embellished, diminished and condensed to convey the central plot and themes. However the title Steve Jobs conveys its own set of basic expectations. Though beautiful in parts, the painting ends up incomplete at best, with areas left sketched out but unfilled.

With its unique three-episode structure, this film is more about its themes than a central plot-line. Symbolism is heaped on gradually, having the audience continuously recall ideas placed strategically throughout the narrative. The “painting” is of Jobs as a man with the desire to control, a desire we all share. This need for control, according to the film, stemmed from the lack of it at the beginning of his life, as well as the complicated relationships with the people around him.

SPOILERS AHEAD!

All of the acting was very good. Michael Fassbender in particular was simply riveting as the title character, though I had problems with other aspects of the performance, which I will explain later. Kate Winslet was also a joy to watch as Jobs’ assistant, Joanna Hoffman, roping in Jobs as he continuously creates his own reality. Even Seth Rogen, whom I don’t usually equate with good acting, was very good in the role of Steve Wozniak.

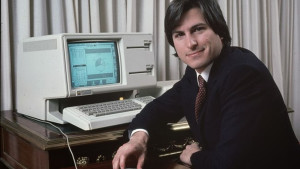

All of the actors were able to evoke some degree of sympathy, which is extremely difficult. Jobs especially could have devolved into a de facto villain of the piece, but as calculating as he is, Fassbender still elicits humanity, making the character accessible. That was the main problem with the 2013 Jobs film – Ashton Kutcher portrayed Jobs as if he was an unfeeling robot, set apart from the people around him.

I was pleasantly surprised by Danny Boyle’s directing choices. It was very measured and even, not as frenetic as some of his other films, like Slumdog Millionaire (though I do enjoy that film). Boyle said in interviews that he studied David Fincher’s The Social Network for inspiration (a story with obvious parallels), and it seems like he learned a lot. Steve Jobs shares Social Network‘s methodical, calculated pacing. It actually made me want to re-watch The Social Network.

Boyle does, however, maintain his own style as well. There are some Boyle-isms strewn throughout, like flying text, visual juxtaposition of exposition, very quick montage cuts, and interesting musical choices.

One of Boyle’s outstanding creative choices was the aesthetic differences between the three acts. The first act was shot on 16mm film, giving it a vintage grain that subconsciously aids the audience in believing that the scene actually took place in 1984. By the time the third act rolls out, everything is streamlined and simple, just like Jobs’ refined design aesthetic. The look of the film evolved with both technology and Jobs’ growth as a character.

One of Boyle’s outstanding creative choices was the aesthetic differences between the three acts. The first act was shot on 16mm film, giving it a vintage grain that subconsciously aids the audience in believing that the scene actually took place in 1984. By the time the third act rolls out, everything is streamlined and simple, just like Jobs’ refined design aesthetic. The look of the film evolved with both technology and Jobs’ growth as a character.

Daniel Pemberton’s eclectic score was terrific, a perfect fit with the world of technology unfolding on screen. There were times when it took on the feeling of 1980s synthesizer music, in which the notes slowly built upon each other in a fun and frantic fashion (the music even kept the beat of a ticking clock at times to subliminally and emotionally remind the audience that time was getting short). Other times it was simple keyboard melodies and full orchestral sounds. Pemberton made use of whatever was necessary to convey feeling without overpowering the scene.

Like Danny Boyle’s direction, the script was not the typical fare of Aaron Sorkin, and I was pleasantly surprised. Sorkin’s scripts are well-written, meticulously constructed and deserving of respect in that capacity. However, Steve Jobs contains very little of his trademark pretentiousness and sarcasm – things I usually don’t care for in his scripts. The wit and ping-pong nature of Sorkin’s dialogue is there, but without the unnecessary venom.

Danny Boyle stated in an interview that a creative decision was made early on not to allow Michael Fassbender to look or sound too much like Steve Jobs. Boyle wanted the energy and the essence of the character to shine through. Fassbender himself admitted that the third act was when they really tried to emulate Jobs in appearance, but only as fan service. This was a mistake that hurt the film.

I found myself constantly distracted by the fact that I was watching Michael Fassbender, as brilliant as he was, playing Steve Jobs, and not Steve Jobs himself. Appearance, especially with a man as known and recognizable as Jobs, enhances verisimilitude. This peculiar mandate was also given to the other actors for some reason. The only actors I thought tried the hardest to emulate their real-life counterparts were Kate Winslet and Michael Sthulbarg.

I give Sorkin credit for coming up with an interesting format for this film. It’s poetic and definitely “thinking different”, to paraphrase Jobs’ influential marketing campaign. However, as lyrical as it is, and as much as it makes for great drama, it can also be constraining. It felt so much like a play in which the entire story takes place in one setting, and not in a good way. Though Apple was undoubtedly a large part of Steve Jobs’ life, I find it extremely hard to believe that one could understand Jobs as a person from those three specific product launches.

Sorkin made the analogy that the film is more akin to a painting than a photograph when talking about Jobs’ life. He wanted to boil down Job’s entire life into three similar events. While this may be true, it may not have been the best way to tell the story of a man like Steve Jobs and with a film title like Steve Jobs. Sorkin said that he didn’t want to make a cradle-to-grave story with Jobs. But with as many experiences as he had, perhaps that may have been the best thing.

Sorkin made the analogy that the film is more akin to a painting than a photograph when talking about Jobs’ life. He wanted to boil down Job’s entire life into three similar events. While this may be true, it may not have been the best way to tell the story of a man like Steve Jobs and with a film title like Steve Jobs. Sorkin said that he didn’t want to make a cradle-to-grave story with Jobs. But with as many experiences as he had, perhaps that may have been the best thing.

This film re-exposed a problem I have had with many biopics in recent years. These films have the subject’s name in the title, but are more about a particular event, or series of events, than the subject’s life as a whole. Films like Hitchcock and Lincoln, while good stories in their own right, have false expectations brought on by the title. One almost subliminally expects the film to be about the life of the person. If the filmmakers were being intellectually honest, the aforementioned films would have been better off being titled The Making of ‘Psycho’ and The Thirteenth Amendment, respectively.

The three acts were gigantic setups with no payoff. I was late getting on the Apple bandwagon, so it would have been nice to have seen part of the product launches themselves, rather than getting a visual bridge to the next act. I found it frustrating when 30 or so minutes was spent leading up to a singular event, but we weren’t able to see it.

Themes and Thoughts

The film’s comparison to a painting is apt. It is full of thematic color and emotion, making a statement with singular images. This makes the themes of the piece much more apparent, and made the film much more enjoyable.

In the film, Steve Jobs’ obsession was control. He wanted to control every part of the experience with his products, but also how the products are introduced. Jobs’ desire for control bled into every aspect of his life, including his relationships with people. We saw him fret over and berate his staff about things like lighting, a picture of a shark, and that the computer must say “hello.” He definitely had a vision, and he wanted things his way.

Chrisann Brennan, his onetime girlfriend, and their daughter Lisa came in and out of the picture to interrupt the supposed serenity of his reality bubble. Here were two people he could not control, and it terrified him. At first, he just wanted them both to go away, and made every effort to make that known.

Chrisann Brennan, his onetime girlfriend, and their daughter Lisa came in and out of the picture to interrupt the supposed serenity of his reality bubble. Here were two people he could not control, and it terrified him. At first, he just wanted them both to go away, and made every effort to make that known.

“Many are the plans in the mind of a man, but it is the purpose of the Lord that will stand.” Proverbs 19:21

We humans desire control. In fact, that has caused many of the ills of this world, such as human enslavement. Human hubris even extends to the environment, where we believe that we can control the climate – as if we could speak to the waves and tell them to stop. And despite our commands, the waves continue to pound the shore.

Some of the best stories ever written have been about humans arrogantly attempting to control forces they cannot comprehend (Jurassic Park, Moby Dick, Gone with the Wind), and they all end the same. They expose human imperfection, which creates inevitable rifts in our “perfect” control.

It’s this penchant for control that has made the way of Jesus Christ so enticing for some and puzzling for others. Jesus tells us that we must pick up our cross and follow Him (Matthew 16:24), relinquishing all control of our lives. Even in Jesus’ day, this was a tall order. We like control, and here is a man telling us to put our faith and our fate in His hands.

In this scene, Apple Executive John Sculley poses a question to Jobs, which prompts him to explain his desire for control:

Rejection is one of the worst feelings we can experience. It cuts even deeper coming from our parents – the ones who are supposed to love us from the instant we are born. One can see how Jobs wanted control to stave off rejection.

Rejection is one of the worst feelings we can experience. It cuts even deeper coming from our parents – the ones who are supposed to love us from the instant we are born. One can see how Jobs wanted control to stave off rejection.

Steve Jobs is a movie as much about parental rejection and acceptance as it is about control. John Sculley was depicted as a father figure to Steve, and Jobs wanted praise from him. That made Sculley’s betrayal much more painful. Jobs himself was seen as a father figure by the people who worked for him, and wanted to some kind of praise from him, but he very seldom gave it.

In one big rush of dramatic irony, Lisa, the daughter he had continuously rejected from birth, began to push him away. This revelation actually concerned him, and a twinge of humanity began to emerge. Jobs realized the truth in what his assistant Joanna said, as she told him to fix his relationship with Lisa:

“I love that you don’t care how much money a person makes; you care about what they make. But what you make isn’t supposed to be the best part of you. When you’re a father, that’s what’s supposed to be the best part of you. And it’s caused me two decades of agony, Steve, that it is, for you, the worst.”

In a brilliant juxtaposition of theme, Jobs let go of control in the third act in order to deepen his relationship with Lisa. He didn’t care about starting the presentation on time – something that he harped about repeatedly throughout the story as a pet peeve of the highest order. Jobs then, in a flash of emotion, admitted apologetically that he is “poorly made.” It was actually quite beautiful.

“A father to the fatherless, a defender of widows, is God in His holy dwelling.” Psalm 68:5

Our earthly fathers have disappointed us sometimes. For many of us, they are a constant disappointment to the point of not even being around, which leaves feelings of bitterness and rejection. But this is because they are human. Many people’s rejection of God as a father figure often stem from poor treatment from their own fathers.

Our earthly fathers have disappointed us sometimes. For many of us, they are a constant disappointment to the point of not even being around, which leaves feelings of bitterness and rejection. But this is because they are human. Many people’s rejection of God as a father figure often stem from poor treatment from their own fathers.

No matter what your earthly father may have done, we all have a Father in heaven who loves us, and wants to know us. We should never feel truly alone knowing this. God loves all of us to the point of death on a cross. His love and wisdom is perfect, and you will never be rejected by Him. That fact makes giving up control of our lives and trusting Him with all our heart that much easier.

Conclusion

Even the process of writing this review makes me reflect upon the impact that Steve Jobs has had on my own life. I’m writing this on a MacBook, while my wife scrolls through Facebook on her iPhone. Jobs certainly made an impact on this world – for good and bad – and his life is a story worth telling.

Even the process of writing this review makes me reflect upon the impact that Steve Jobs has had on my own life. I’m writing this on a MacBook, while my wife scrolls through Facebook on her iPhone. Jobs certainly made an impact on this world – for good and bad – and his life is a story worth telling.

I liked Steve Jobs. It’s a great movie, and an interesting character study of man who has made and huge impact upon the whole world. It’s ironic that this film is simplified and streamlined, much like Apple’s products, but cannot fully capture the complete picture of this complicated man.

When we desire full control in our lives, we often steer ourselves toward disaster. We are not poorly made, but we are poorly governed by the fickle desires of our own hearts. We need, and were made for, a perfect God to take control of our lives – a God who can see into eternity, and is infinitely more wise than any of us. We still have choices to make in life, but those choices are easier knowing that God has our ultimate good in mind.

Pingback: #078 – Steve Jobs and Losing Control | Reel World Theology