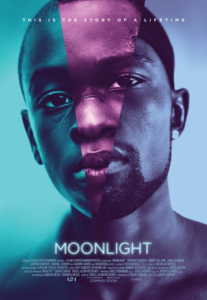

Review| Moonlight and An Opportunity for Empathy

Roger Ebert lamented in his 2005 review of Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain

Roger Ebert lamented in his 2005 review of Ang Lee’s Brokeback Mountain, “‘Brokeback Mountain’ has been described as ‘a gay cowboy movie,’ which is a cruel simplification.” Ebert was pushing back at the prevailing opinion Lee’s movie was nothing more than a sensationalized movie about “gay cowboys” with a big name director and cool, youthful stars (Heath Ledger and Jake Gyllenhaal). His refusal to simplify the movie was an effort to see through the dark cloud of cultural unfamiliarity to find the light of greater meaning and common experience found in a story most people will not resonate with on a surface viewing.

Moonlight, is a deeply empathetic story similar to Brokeback Mountain in its exploration of unrequited love in a cultural milieu where homosexuality was not only scandalous but actively stigmatized–Moonlight taking place in the urban, predominantly African-American Miami. Following one young man, Chiron, the movie chronicles three chapters in his life starting as a scared, neglected youth. It is split into three acts, owing this division to it’s origins as a play written by Tarell Alvin McCraney. When we meet Chiron, he is “Little”, a derisive nickname for his stature, and running from a group of boys, escaping only when ducking into an abandoned apartment building. Inside he meets Juan, a drug dealer in the neighborhood who tries to help him find his way home. When Chiron deigns to speak a word to Juan, he takes the young boy to his home and to his girlfriend, played by Janelle Monae. Her friendliness combined with a plate of food, a common motif used to signify relationship and connection, loosens Chiron’s tongue and he confesses he does not want to return home to a neglectful, drug-addicted mother.

Mahershala Ali as Juan is the best performance in the entire movie. Despite his limitation to only appearing in the first act, Ali quickly becomes a father-like figure to Chiron, and Teresa, Juan’s girlfriend, a motherly influence. On the surface, a street tough bent on enforcing his turf, Juan sees himself as a self-made man, rising above the poverty and his circumstances. In one of many scenes boasting incredible technical and artistic merit, Juan teaches Chiron how to swim. With a magnificent string score by Nicholas Britell, the camera bobs in and out of the water capturing this intimate moment of connection as Juan teaches him a measure of self-sustainability. There is a spiritual, baptism-like quality in this moment where Juan almost transfers a part of himself to “Little”.

However, breaking the cycle African-American youth among urban crime and drug use proves much more difficult than Juan would idealistically hope. Chiron’s neglect by his mother due to drug abuse and Juan’s illicit activity as a drug dealer collide in Ali’s final, gut-wrenching scene at the conclusion of the first act. It is a telling picture of the isolation Chiron faces in his Liberty Square neighborhood and the inescapable hardship of being African-American in urban cities in the US.

Act 2 of Moonlight introduces this relationship for Chiron as he continues to wrestle with his realization of being gay, a fact mentioned off-handed in Act 1. Kevin, a childhood friend who turns out to be more than the lady-killing player he makes himself out to be. Chiron clearly harbors a secret attraction to his friend, but the stigma of such a desire and Kevin’s boisterous attitude seem incongruous to his longing ever becoming a reality. Even when those feelings are returned, the are quickly dashed and Act 2, once again, ends with Chiron’s isolation and an explosive, life-changing choice.

Director Barry Jenkins is no stranger to placing social commentary within the context of a complex, personal narrative. His previous feature-length movie, Medicine for Melancholy, sets a one-night stand and budding romantic relationship against the backdrop of gentrification and urban segregation in modern San Fransisco. The main story focus is on the well-acted relationship between actors Wyatt Cenac and Tracey Heggins, but the powerful story around is one of greater social significance and comes to impact their eventual parting at the end of the movie.

In the same way, the final act, called “Black”, has accrued both Chiron’s powerful, unseen social and cultural influences and his awkward, hesitant relationship with Kevin. Riffing powerfully on the thematic and stylistic influences of Wong Kar-Wai, the movie grapples with how adulthood has reinforced what they have known to be acceptable since youth, but under the surface they long to be truly known as they once were, briefly, in the moon’s pale glow. The final moment of Act 3, unlike the previous two, is gripping and unexpected enough to avoid spoiling, but it powerfully counterpoints the previous two acts’ endings and sounds a hopeful final note over Chiron’s story.

Of all the strengths in Moonlight, the greatest of these is the chance to listen. In a forthcoming episode of the Feelin’ Film Podcast, Aaron White and I discussed the audiences at our screenings of this movie and how it represented groups of older, white Americans who would never cross paths with a gay, African-American male growing up in urban America. Roger Ebert famously called movies, “a machine that generates empathy,” and although empathy has gotten a bit of a bad rap as of late, his maxim still proves abundantly true. Jenkins’ film deeply connects with how isolating the world can be to people of color, different sexual orientation, and even those involved with or selling drugs. We may never fully understand the black experience in American nor morally condone a person’s sexuality or drug use, but Moonlight strikingly and vividly paints a gentle mosaic of the complex nature of these matters and allows us to respond in a more gracious, understanding, and grace-filled manner.

Wonderful piece, Joshua!

Thank you Don and thanks for reading!

Pingback: Josh’s Top 10 Films of 2016 | Reel World Theology