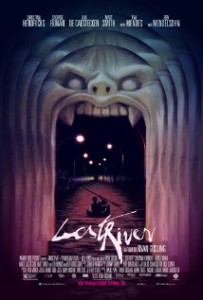

Review| Lost River

Ryan Gosling’s debut as a director is an ambitious mess. As an actor, he’s come a long way from early films and matured into a capable, brooding, interesting actor who tackles a diverse load of projects. Lost River certainly ain’t The Notebook, and finds much in common with Gosling’s recent collaborative work with director Nicolas Winding Refn. Clearly influenced by Refn, David Lynch, and John Carpenter, Lost River features bizarre and haunting images stretched around a paper-thin plot that holds the viewer at a distance.

Ryan Gosling’s debut as a director is an ambitious mess. As an actor, he’s come a long way from early films and matured into a capable, brooding, interesting actor who tackles a diverse load of projects. Lost River certainly ain’t The Notebook, and finds much in common with Gosling’s recent collaborative work with director Nicolas Winding Refn. Clearly influenced by Refn, David Lynch, and John Carpenter, Lost River features bizarre and haunting images stretched around a paper-thin plot that holds the viewer at a distance.

The town of Lost River is dying, and so are the hopes of Billy (Christina Hendricks), a single mother with two boys living in the decrepit remains of her childhood home. Surrounded by abandoned buildings tottering from neglect, the only things that seem to thrive in Lost River are weeds, rust, and violent thugs. Billy’s teenage son Bones (Iain De Caestecker) earns money by stripping copper from the neighborhood in order to buy parts for his rusty car, though he’s always on the lookout for Bully (Matt Smith), the local small-time gangster. Billy takes on a new job from her banker, Dave (Ben Mendelsohn), who hires her as a performer for his seedy, morbid nightclub known for its pseudo-violent productions. Billy’s desperation is evident; she clearly doesn’t want her sons to know about her job, but she’ll also do anything to keep their house. Bones’ motives are unclear—we’re not sure if he’s trying to save the house, or earn enough funds to help his family escape their deteriorating environment. When Bones discovers an underwater city in the nearby reservoir, he turns to his neighbor Rat (Saoirse Ronan) for insight and friendship, plunging them into a dangerous journey to discover the history of Lost River and break the spell that seems to hold it captive.

While each of these characters should be more interesting, the tone of Lost River is standoffish, almost like it refuses to engage with the audience. We may pity Billy or have sympathy for Rat, but we never empathize with them or truly understand them. We’re allowed to see Lost River, but never wholly enter the town. Gosling’s camera hovers and spins, and the cinematography is fascinating but distant. Like the murky waters that cover the subterranean city, we see Lost River and its inhabitants through a glass dimly. The performances are either minimalist and quiet or extravagant and ridiculous. Matt Smith, in particular, stands out as an impulsive, violent goon who often screams at random, and Mendelsohn is his usual unsettling self. The overall narrative is also quite sparse, making the film feel far longer than it actually is—a 95 minute movie that drags. Without a clear story or direction, the images on screen aren’t grounded in anything substantial. It’s difficult to pin Lost River in terms of genre—elements of fantasy, crime, noir, romance, and drama are all present, but nothing truly stands out. In a sense, Lost River is beyond definitions; it doesn’t seem to care much what it is, only that it is.

While each of these characters should be more interesting, the tone of Lost River is standoffish, almost like it refuses to engage with the audience. We may pity Billy or have sympathy for Rat, but we never empathize with them or truly understand them. We’re allowed to see Lost River, but never wholly enter the town. Gosling’s camera hovers and spins, and the cinematography is fascinating but distant. Like the murky waters that cover the subterranean city, we see Lost River and its inhabitants through a glass dimly. The performances are either minimalist and quiet or extravagant and ridiculous. Matt Smith, in particular, stands out as an impulsive, violent goon who often screams at random, and Mendelsohn is his usual unsettling self. The overall narrative is also quite sparse, making the film feel far longer than it actually is—a 95 minute movie that drags. Without a clear story or direction, the images on screen aren’t grounded in anything substantial. It’s difficult to pin Lost River in terms of genre—elements of fantasy, crime, noir, romance, and drama are all present, but nothing truly stands out. In a sense, Lost River is beyond definitions; it doesn’t seem to care much what it is, only that it is.

While standoffish, some of Lost River’s images are both deeply affecting and extremely weird. I scribbled some of these images down in my journal: A burning house. Twirling and dancing in the abandoned hall. Cuts her face off. Night drives. No lips. Pink haze. Dinosaur head. If those images sound intriguing, or if you’ve always wanted to see a creepy Ben Mendelsohn sing and dance around the room, this is the film for you. Accompanying these images is the 1980s-era pulsing, droning electronic soundtrack. Featuring various artists, but mostly Johnny Jewel and the Chromatics, the score is sweeping and strange, both foreboding and comforting, and might be the strongest aspect of the whole film. (I downloaded the score off iTunes the following day. It’s been excellent background music for writing this review).

While standoffish, some of Lost River’s images are both deeply affecting and extremely weird. I scribbled some of these images down in my journal: A burning house. Twirling and dancing in the abandoned hall. Cuts her face off. Night drives. No lips. Pink haze. Dinosaur head. If those images sound intriguing, or if you’ve always wanted to see a creepy Ben Mendelsohn sing and dance around the room, this is the film for you. Accompanying these images is the 1980s-era pulsing, droning electronic soundtrack. Featuring various artists, but mostly Johnny Jewel and the Chromatics, the score is sweeping and strange, both foreboding and comforting, and might be the strongest aspect of the whole film. (I downloaded the score off iTunes the following day. It’s been excellent background music for writing this review).

Lost River attempts to offer a theology of place, a meditation on the concept of “home.” Filmed in the wastelands surrounding the city of Detroit, one recognizes that these houses and neighborhoods have a history, that they were once full of life and hope, only to deteriorate through abandonment and neglect. Billy and Rat have hope for their homes—their place, their land—but the corrupt powers that surround them are forcing all into exile. The powers surround all of us, threatening to displace and disorient. Houses burn. Weeds grow. Towns flood. Nothing lasts forever. Our only hope is in the relationships we form, the people we love. “What’s keeping you here?” Rat asks Bones, wondering if he’ll speak her name in reply.

I watched this tonight. It is really endearing to me, and I really liked the soundtrack, too. I loved so much about it, but I definitely need to watch it again to form a complete opinion.