Review| Hold the Dark

Director Jeremy Saulnier’s growing filmography should be getting much more attention. He surprised everyone with the low-fi action thriller Blue Ruin in 2013. Eschewing typical conventions within the genre, Saulnier’s barely proficient yet galvanized everyman protagonist Dwight, played by friend and collaborator Macon Blair, dives headfirst into a brutal but heartbreaking journey of revenge. Likewise, 2015’s Green Room doubled down on Blue Ruin‘s aesthetic with a thumping hour-and-a-half of blood, volume, intensity, and a sharp political commentary that proved to be more ominous than when it first released in early 2016. In both his more well-known movies and his lesser known 2007 Murder Party, his protagonists are confronted with the brutal, sharp-edged elements of humanity. Saulnier’s movies instinctively observe the grisly results a subdued, uncomfortable realism with little or no easy answers.

Director Jeremy Saulnier’s growing filmography should be getting much more attention. He surprised everyone with the low-fi action thriller Blue Ruin in 2013. Eschewing typical conventions within the genre, Saulnier’s barely proficient yet galvanized everyman protagonist Dwight, played by friend and collaborator Macon Blair, dives headfirst into a brutal but heartbreaking journey of revenge. Likewise, 2015’s Green Room doubled down on Blue Ruin‘s aesthetic with a thumping hour-and-a-half of blood, volume, intensity, and a sharp political commentary that proved to be more ominous than when it first released in early 2016. In both his more well-known movies and his lesser known 2007 Murder Party, his protagonists are confronted with the brutal, sharp-edged elements of humanity. Saulnier’s movies instinctively observe the grisly results a subdued, uncomfortable realism with little or no easy answers.

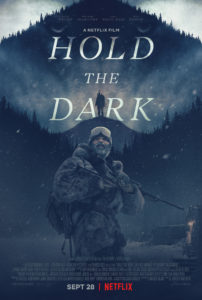

His latest output, Hold The Dark, lengthens the thread of this aesthetic with another muted, savage film set in the Alaskan wilderness. When mother Medora Slone (Riley Keough) has her son taken by wolves, she writes to a Russell Core (Jeffrey Wright), a writer and wolf expert, to come to their remote town of Keelut to hunt down the wolf who took her son. After he arrives, nothing is what it appears as he is dragged into the darkness and hostility of the Alaskan winter where the people are just as fierce as the untamed wilds surrounding Keelut. Cloaked in a mood of ominous apprehension, Core’s expertise with wolves does little to prepare him for the savagery found amongst the glistening beauty of this northern Alaskan town nor the inevitable bloody odyssey in which he is enveloped. It is not surprising Saulnier’s movie, written by Macon Blair who also plays a small role late in the runtime, delves into his familiar themes of common people being capable of shocking violence. However, for the first time in his movies, it connects directly to the beauty and savagery of the natural world and aspires to tackle bigger questions of spiritual reality and meaning.

Likening itself to Saulnier’s previous work, Hold the Dark contains a fair number of gory moments featuring practical effects. It is hard to forget the machete to Anton Yelchin’s arm in Green Room, and this movie has at least three similar moments of quick head-turn-away gore sure to keep the viewer on edge. Contrasted with these squeamish, grisly moments is the beauty of the small towns surroundings where Wright’s Russell Core is sent to investigate the disappearance of Slone’s boy. Armed by Netflix with a slightly bigger budget, Saulnier majestically films the landscapes of Alaska, capturing its pristine snowscapes as well as the vastness of its dark, verdant spruce and skeletal, snow-caked firs. Despite the writer’s own residence in a snow-laden state and opinions about the malignant nature of winter’s crystalline progeny, the movie conveys the breathtaking wonder and bone-chilling danger of the wintry landscape and is epitomized in the wolves Core is hired to track.

The wolf is a natural contradiction. Composed of sleek elegance and long the fascination of both nature enthusiasts and corny T-shirt makers alike, wolves are pretty animals. Their further direct lineage to domesticated dogs only heightens our esteem. And yet, wolves are incredibly dangerous animals. Long hunted on the North American continent for their predation of other domesticated animals, wolves ferocity is well known. The movie even captures this in an early scene where Core tracks a pack of wolves only to find them eating one of their own young, a phenomenon known as “savaging”. This contradiction of beauty and savagery is integral to the aesthetic of the film as well as the main narrative thread exploring human depravity and the unforgiving quality of nature.

The wolf is a natural contradiction. Composed of sleek elegance and long the fascination of both nature enthusiasts and corny T-shirt makers alike, wolves are pretty animals. Their further direct lineage to domesticated dogs only heightens our esteem. And yet, wolves are incredibly dangerous animals. Long hunted on the North American continent for their predation of other domesticated animals, wolves ferocity is well known. The movie even captures this in an early scene where Core tracks a pack of wolves only to find them eating one of their own young, a phenomenon known as “savaging”. This contradiction of beauty and savagery is integral to the aesthetic of the film as well as the main narrative thread exploring human depravity and the unforgiving quality of nature.

The movie delves ever deeper into savagery as the movie gets darker. Not only is the winter a time of the solstice when the light is scant, but a shrouding darkness permeates the movie as Alexander Skarsgård’s Vernon Slone enters the picture. Saulnier plays with tonal shifts within the movie, with the middle act a shadowy massacre before finally retreating again into the drifts of the Alaskan mountain ranges and the final third. In this transition, one character asks of another, “Why any of it?” The response is telling and feels like something lifted straight from Cormac McCarthy, “[Answers] do exist, whether they fit into our experience in another matter.” Their musing on “why” all this savagery is only to bring an end to darkness. The nihilistic point hints at a meaningless answer but stresses something deeper in the filmic text.

As the movie ends and blood spots the snowy ground, one character is left to reconcile with a love thought lost. When the character is asked to relate what happened, the movie ends with his words, “I’ll tell you.” It seems like a silly word to end, but Saulnier’s work has always ended this obtuse. The “I’ll tell you,” is an expression of hope in finding a light in the darkness, to making hope out of a hopeless situation. Beauty can be a veil of savagery but also spring forth out of the greatest pain. What we can hope to accomplish is hold the dark to find hope in the light.