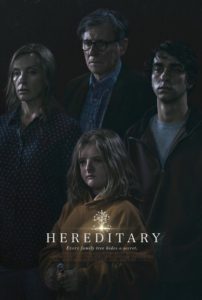

Review| Hereditary

There is a significant distinction between a tragic hero and a foregone conclusion. While both retain the characteristic of giving the audience foreknowledge of their impending fate, only the tragic hero invites the will of the audience to push against the hurricane of that fate. Tragic heroes have this ability because they are ultimately relatable to us as viewers or readers. They are generally good people who have flaws and errors in judgment that lead to their eventual demise. At no point is the audience cheering for the excessive punishment that will befall them, because they don’t fully deserve what’s coming to them. A character who is a foregone conclusion, however, is predictable and static in their choices. They start out one way and they continue to act that way. Sometimes they can be quirky and given an interesting backstory or modus operandi, but the audience never doubts or cares to doubt what will come of them

There is a significant distinction between a tragic hero and a foregone conclusion. While both retain the characteristic of giving the audience foreknowledge of their impending fate, only the tragic hero invites the will of the audience to push against the hurricane of that fate. Tragic heroes have this ability because they are ultimately relatable to us as viewers or readers. They are generally good people who have flaws and errors in judgment that lead to their eventual demise. At no point is the audience cheering for the excessive punishment that will befall them, because they don’t fully deserve what’s coming to them. A character who is a foregone conclusion, however, is predictable and static in their choices. They start out one way and they continue to act that way. Sometimes they can be quirky and given an interesting backstory or modus operandi, but the audience never doubts or cares to doubt what will come of them

Hereditary aims for classic tragedy which can be seen by way of the various references to tragic plays and myths that the director, Ari Aster, none too subtly drops into the narrative. The film opens with the Graham family getting ready for a funeral of a grandmother, the mother of Annie (Toni Collette) who sits in the car with more anxiety than grief. Her husband (an underused Gabriel Byrne) rallies their son, Peter, (Alex Wolff) and daughter, Charlie. We find out that she and her mother (and their whole side of the family) had a fraught relationship that was only amplified by mental illness that ran in the family. From this point on, the audience enters into a world of deadly sleepwalking, potential psychosis, ghosts and creepy little miniatures created by Annie. As we learn more and more about family history and relational dynamics, we begin a familial descent into hell

Hereditary attempts to plow the fertile ground of mythology, genetics, grief and mental illness for meaning, but its plow’s coulter and plowshare appear to be worn and the product feels a bit slipshod with several potential subtexts never quite finding cohesion. By the time the ending’s heavy-handed homage to Rosemary’s Babyand The Wicker Man(and other horror fare from the 70s) takes place, even the singular power of each loose strand ends up nullified by a singular—quite literal—interpretation of events by the film.

Everything about this film—its acting, its promising filmmaking, the ideas it touches on—is ripe picking for an avid horror fan. However, somewhere along the way Aster forgot the first rule of good mythology, the story must have a tragic hero. Someone who is virtuous, relatable and gains the audience’s sympathy before their flaw, error of judgment or pride bends them toward an excessively brutal end. There might be elements of Annie that are relatable to those who live in familial situations plagued by mental disorders, but she never comes off as sympathetic; she is never given a chance to be. The film takes up in the midst of the descent, so we meet our supposed hero when she is detached and all we get to experience of her character from that point on is her road to madness. Instead of a tragic hero whom we hope is able to avoid what feels inevitable, Annie ends up being a foregone conclusion. None of her actions speak otherwise.

Everything about this film—its acting, its promising filmmaking, the ideas it touches on—is ripe picking for an avid horror fan. However, somewhere along the way Aster forgot the first rule of good mythology, the story must have a tragic hero. Someone who is virtuous, relatable and gains the audience’s sympathy before their flaw, error of judgment or pride bends them toward an excessively brutal end. There might be elements of Annie that are relatable to those who live in familial situations plagued by mental disorders, but she never comes off as sympathetic; she is never given a chance to be. The film takes up in the midst of the descent, so we meet our supposed hero when she is detached and all we get to experience of her character from that point on is her road to madness. Instead of a tragic hero whom we hope is able to avoid what feels inevitable, Annie ends up being a foregone conclusion. None of her actions speak otherwise.

Peter, on the other hand, seems to be apt as our tragic protagonist, but the camera very seldom strays from Annie and his character is not given enough development or screen time for us to glom onto him as our tragic avatar. The guilt and grief he has over the only unpredictable moment in the film is relatable and worthy of sympathy and pity, yet we are continually brought back to the increasingly frantic and questionable mental state of his mom. There is no point in the film in which it could be believed Annie will shift her trajectory or that we would expend our energy to hope for it to shift, because throughout the film her actions seem more deserving of her fate than any other character in the film. The film’s tragic flaw is that while it’s a joy to watch an actress descend into madness and enjoy every minute of it, the character she is playing is never given levity or moments of clarity for her to push back against the fate Aster has placed on her.

What we are left with then is a stylish psychological vision of hell on earth where people either die or live long enough to go crazy. Yet for all of the good attributes that the film has, there is nothing that remains under the skin—irritating us until we confront it—and a sense that the film might have been better if its creator had actually cared for his characters instead of sentencing them to be nothing more than cogs in his Dante-esque machinery.

What we are left with then is a stylish psychological vision of hell on earth where people either die or live long enough to go crazy. Yet for all of the good attributes that the film has, there is nothing that remains under the skin—irritating us until we confront it—and a sense that the film might have been better if its creator had actually cared for his characters instead of sentencing them to be nothing more than cogs in his Dante-esque machinery.

Pingback: [Chris] All is Not Right Here: Hereditary and the Horror of Embodied Trauma – Grindhouse Theology