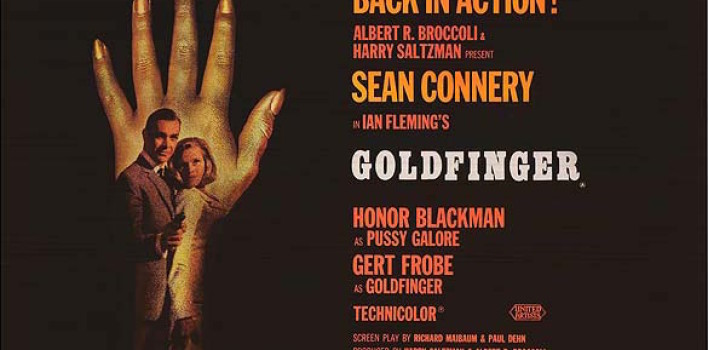

Review| Goldfinger

The cold open of a James Bond movie is always one of the best parts of 007’s cinematic adventures. A seagull floating in the water near a dock is revealed to be merely a decoy. After ascending the docks’ ladder, everyone’s favorite British MI6 Agent quickly and covertly steals into a drug factory. After setting explosives, he sheds his tactical gear to unveil a dashing white suit, complete with a red rose. He enters a nightclub, finds a table, and lights a cigarette as the night sky erupts in destroyed narcotics. Naturally, Bond uses this triumphant moment to return to wooing the local bombshell, only to be set up for a surprise attack. One fist fight, bathtub electrocution, and pithy one-liner later, it cuts to Goldfinger’s iconic title music.

The cold open of a James Bond movie is always one of the best parts of 007’s cinematic adventures. A seagull floating in the water near a dock is revealed to be merely a decoy. After ascending the docks’ ladder, everyone’s favorite British MI6 Agent quickly and covertly steals into a drug factory. After setting explosives, he sheds his tactical gear to unveil a dashing white suit, complete with a red rose. He enters a nightclub, finds a table, and lights a cigarette as the night sky erupts in destroyed narcotics. Naturally, Bond uses this triumphant moment to return to wooing the local bombshell, only to be set up for a surprise attack. One fist fight, bathtub electrocution, and pithy one-liner later, it cuts to Goldfinger’s iconic title music.

However, the opening sequence was only an appetizer, a sumptuous canapé of the ingredients that make Goldfinger one of the best Bond films and the template for every movie after it. 007’s dashing suits? Check. Pretty Bond girls? Check. Sinister and iconic villains? Check. Memorable henchmen? Check. Flirting with Moneypenny? Check. Gadget briefing with Q? Check. Tricked out European car? Check. Famous Bond lines? Double check. Satisfying everything we’ve come to know and love about 007, the third cinematic installment of Ian Fleming’s famous spy became the gold standard for what a James Bond movie was and is supposed to be.

After 007’s initially explosive caper in Latin America, our hero is swept up in an investigation of the allegedly crooked businessman, Auric Goldfinger. Their first encounter seems to go Bond’s way, with Bond’s detective work costing Goldfinger a handsome sum from a game of gin rummy. However, Bond’s fling, Jill Masterson, is Goldfinger’s revenge. Bond is knocked out by a mysterious, bowler sporting man and when he awakes, in the one of the most memorable moments of any Bond film, he finds Jill dead and covered in gold paint. Clearly, 007 is dealing with more than just a corrupt businessman.

After a briefing in London, complete with Q’s outfitting of the latest gadgets, Bond follows Goldfinger to Switzerland. He races a pretty girl, tries to sneak into Goldfinger’s Swiss plant, and ends up a prisoner of Goldfinger. He awakes on a plane bound for Baltimore under the watchful gaze of Pussy Galore. That’s right, you read that correctly. Our Bond girl has one of the best worst names ever. She’s deadly, intelligent, and beautiful; but she works for the other side. Bond is smitten, but he has no time for it as she is shuttled to Goldfinger’s lair masquerading as a horse farm in rural Kentucky.

In the country club of this horse farm, we are treated to another iconic Bond moment. He’s strapped, legs and arms spread out, to a table made of gold. As Goldfinger monologues, a powerful cutting laser begins to cut the gilt table in half and threatens 007 to suffer the same fate. When James asks Goldfinger if he expects him to talk, the megalomaniac retorts, “No, Mr. Bond, I expect you to die.” It’s a fabulous zinger and by far one of the best moments in Bond history.

Of course, it would be easy to continue disclosing the all of Bond’s exploits, but you know the score. Villain pontificates his secret, absurd plan, Bond thwarts it, gets the girl, and the day is saved. If the formula seems incredibly wrote, it’s because Goldfinger perfected it. There was much more action that made it a movie experience instead of a book adaptation the first two movies had been. The changes that made the movie more exciting are worth applauding, but credit also belongs to the man who embodied the essence of the debonair British agent.

Synonymous with the Bond character is, at the time, unknown actor Sean Connery. Even decades after playing the part, he is still linked and honored for his role as Her Majesty’s finest MI6 operative. In Connery’s films, Bond is urbane; a man of refined tastes and upscale manner. However, he’s cheerful, even in the direst of circumstances. And he is always keen on a woman to woo. But, while Connery’s charisma and rakish good looks became standard-issue when re-casting Bond, it was his self-assurance and hardened tenacity that set him apart from other actors playing 007. Connery’s Bond isn’t the later re-booted action star. In fact, he is often woefully inadequate at extricating himself from tough spots. Yet when the chips are down, Bond is a knot of grit and resourcefulness that keeps him alive and progressing towards mission completion.

The chemistry of Connery with his co-stars, Gert Fröbe as Auric Goldfinger and Honor Blackman as Pussy Galore, is also of particular note. While both characters boast silly names, a Bond staple, there is a simplistic psychosis in Goldfinger’s villainy. He views his ultimate objective, Fort Knox, as the Everest of crime. He has no plans to wipe out the world or exact revenge; his myopic objective is health and power. It’s almost refreshing amidst the deluge of super-villains bent on apocalyptic scale destruction in today’s superhero movies. And of course, I would be wont not to mention his henchman, the burly, gruff Korean assassin, Odd Job. He is, by far, one of the coolest characters in Bond history, and also the best character to play in N64’s Goldeneye. That is if you want your friends to not like you anymore.

Likewise, Blackman and Connery’s chemistry as two deadly, trained agents on opposing sides is playful and amative. From the get go, it is obvious these two will eventually get together at some point in the movie, yet the moment is teased and their banter is casually seductive and equally hostile. And Galore is no pushover. Trained in martial arts, a fighter pilot in charge of an all-woman, all-blonde flight group called her “Flying Circus”, she certifiably a different “Bond girl” than the pre-gold, pre-dead Jill Masterson. Jill’s bona fides are nothing more than a bathing suit and “repaying” Bond with a night together. Galore, by contrast, is self-assured, confident, and capable of handling herself in a battle of wits or a battle of fists.

Which is why her eventual “submission” to 007’s “charms” reads like nothing else than rape and a sad, troubling view of even “tough women”. Goldfinger instructs Galore to change into a more alluring outfit to make sure Bond, his prisoner, is “satisfied” in every way. She dutifully obeys but once Bond and her stroll to a horse barn, she seems uncomfortable and agitated by Bond’s advances. They have some heated and sexually charged dialogue while judo chopping one another. Bond gains the upper hand, throws her to the straw, holds her down and kisses her while she resists adamantly. The scene fades out as she seems to give in to his kiss and it is implied they have intimate relations with one another. Troubling might be an understatement.

The scene shares uncomfortable similarities to another barn rape scene in Clint Eastwood’s High Plains Drifter. But where Eastwood’s “Stranger” is a mysterious, anti-hero, James Bond is portrayed and lifted up as a hallmark of masculinity and heroism. It begs a deeper question: what has changed in what we want in a hero from the 1960’s to now? Furthermore, what does it mean to be a man then and now?

The most admirable aspect of James Bond is a soldier-like attachment to his mission and a callous disregard for anything that stands in his way. We love Bond because he is decisive, confident, and unyielding even when the odds are stacked against him. Truly he is a man from the age of people like my father and grandfather. What we would call a “man’s man”. There is no emotion, no deeper pathos in your duty or your responsibilities. You put your head down and you accomplish your objective with little complaint and a casual wave of the hand to your vices.

However, is that all good? Certainly not if we look at 007. Multiple actors who have played Bond; George Lazenby, Sean Connery, and most recently Daniel Craig have all expressed disgust at the character of Bond and labeled him as “a brute”, “misogynistic”, and have wished him dead. Bond clearly has a weakness for women, but it is portrayed like another hedonistic creature comfort on par with his love of a well-shaken martini or an Aston-Martin DB5.

However, is that all good? Certainly not if we look at 007. Multiple actors who have played Bond; George Lazenby, Sean Connery, and most recently Daniel Craig have all expressed disgust at the character of Bond and labeled him as “a brute”, “misogynistic”, and have wished him dead. Bond clearly has a weakness for women, but it is portrayed like another hedonistic creature comfort on par with his love of a well-shaken martini or an Aston-Martin DB5.

The James Bond of Goldfinger and of the wider franchise is a double-edged sword. His qualities of duty to country and taking down the bad guys are quintessential heroic traits men and women would do well to imitate and aspire to. Yet, his iconic status as a bastion of masculinity is called into question by his treatment of the opposite sex, whose company he is renowned for enjoying. In Goldfinger, one of the upper echelon movies of the franchise, his cold nonchalance towards women can’t hide behind all the iconic moments and catchphrases. To ignore his foibles is to ignore the impact his character has had on both reflecting and shaping our culture’s view of women and masculinity. In fact, the two most recent incarnations of Bond have tackled some of these objections and acknowledged the Bond character must be viewed with a discerning eye. To not do so is to risk missing what makes 007 great, controversial, and also worth talking about.