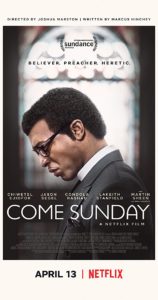

Review| Come Sunday

I was once a heretic. As a confirmed communicant and a born and raised Catholic, The church would not have been happy to know I confidently believed you didn’t need to believe or practice Catholic doctrine to be accepted by God and in heaven with Jesus. However, this was nothing special. I’m pretty sure most of my Catholic friends believed the same thing. Also, I wasn’t an enthusiastic teacher with the blessing of the church and an active ministry. On the contrary, I was one of the millions of regular congregants in a suburban church. I certainly wasn’t the celebrated pastor of a suburban megachurch congregation. Come Sunday is the story of a much higher profile heretic.

I was once a heretic. As a confirmed communicant and a born and raised Catholic, The church would not have been happy to know I confidently believed you didn’t need to believe or practice Catholic doctrine to be accepted by God and in heaven with Jesus. However, this was nothing special. I’m pretty sure most of my Catholic friends believed the same thing. Also, I wasn’t an enthusiastic teacher with the blessing of the church and an active ministry. On the contrary, I was one of the millions of regular congregants in a suburban church. I certainly wasn’t the celebrated pastor of a suburban megachurch congregation. Come Sunday is the story of a much higher profile heretic.

Calling Carlton Pearson, Come Sunday‘s main protagonist, a heretic is a label embraced by the filmmakers. Based on the true life events of Bishop Carlton Pearson, the narrative itself adheres very tightly to the podcast episode of This American Life it is adapted from titled “Heretic”. A celebrated pastor of Higher Dimensions Family Church, a diverse megachurch congregation in Tulsa, a celebrated graduate of Oral Roberts University, and protege of the University’s eponymous founder, Pearson was on a path to widespread recognition and influence in Pentecostal churches. The movie chronicles the loss of his ministry after he sees a TV program of the Rwandan genocides and has an epiphany where God tells him there is no hell except the one humans create on Earth. As a result, Pearson begins to preach a version of universal reconciliation he calls “the gospel of inclusion,” and it leads to much of his congregation leaving, losing favor with Oral Roberts, and being eventually labeled a heretic by his peers from the Joint College of African-American Pentecostal Bishops.

Director Joshua Marston, screenwriter Marcus Hinchey, and producer Ira Glass do their very best to avoid taking sides theologically or turning the movie into a Pure Flix production for liberal theology. However, because of its subject matter and protagonist, the movie does end up as a celebration of Pearson’s doctrine. At first, it only pertains to his preaching of universal salvation and supplies the main tension of the narrative. When deciding to preach his message, he comes into conflict with his long-time friend Henry, who is a founder and elder of his church along with him. Played by Jason Segel in one of the many solid performances in the film, Henry is portrayed as conflicted between his affection for Carlton, his deep investment in the church, but also his own theological convictions. Likewise, Martin Sheen plays Oral Roberts, Pearson’s mentor and friend, who is significantly tougher on the bishop’s theology when he will not recant but is equally torn given his relationship and investment in Pearson.

Eventually, the movie does progress from soteriological concerns to ones of morality as the movie unwraps the natural progression of Pearson’s theological conclusions. The morality concerns are encompassed by Reggie, leader of the church choir played by Lakeith Stanfield. Reggie enthusiastically embraces the gospel of inclusion but finds himself vexed when confronted with his homosexuality, which he has previously always believed to be a sin. Initially, he is rebuked by Pearson after he starts a relationship with another gay man. Yet despite the sharp admonition, he stays with Higher Dimensions and continues to play piano until he collapses and reveals he has HIV. Pearson must confront his own belief of homosexuality being a sin as Reggie’s health goes south from HIV and prays with Reggie to be accepted for who he is, not for what others say the Bible tells him to be.

If any clearer signal of the movie’s intent is needed, the last two scenes are Pearson heading down to a river and baptizing himself with water and then speaking at a Unitarian church with a diversity of people from different ethnic groups, sexual orientations, and gender identities and ends with a choral rendition of “Jesus, I’ll Never Forget.” For him it is a moment of clarity and conviction, being sanctified for a new mission to spread his gospel of inclusion.

This movie is troubling. For the studious Christian believer, the proof texts given for Pearson’s position can easily be refuted by an introductory class in hermeneutics. However, for the general audience perusing Netflix for a movie to watch, it could easily cause turmoil, confusion, and cast doubt on the authority and fidelity of Scripture and biblical doctrine. The movie does not set out to be a definitive argument for Pearson’s position, however, the forward momentum of the narrative empathizes with Ejiofor’s character as reasonable, likable, and in the right. While there is nothing wrong with a movie portraying its main protagonist in a positive light, it makes it impossible without digging further into the Scripture and theology used to discern if what Pearson says is either a correct or incorrect interpretation of the what the Bible says about salvation and hell. Therefore, I would advise against recommending this movie to a general audience without some major caveats.

Even though I disagree strongly with Pearson’s beliefs and interpretation of Scripture and the filmmaker’s celebration of his message, it is impossible to fully write off this movie. It gets theology wrong. And yet, it offers a sensitive, painfully accurate portrayal of how the church often mishandles the fall or departure of a leader and seeks to understand the humanity of a wandering shepherd.

As a pastor, it was difficult to watch this movie. I’ve been let go from a church, albeit for financial reasons, but Pearson’s own experience in Come Sunday is achingly real. In the This American Life episode “Heretic”, he describes losing his congregation as his people having a funeral for him and then moving on. I have never had it described more accurately than this. Once he presents his new teaching to his people, the movie’s mood shifts to a eulogy. Segel’s Henry embodies this slow drift as he wrestles with the turmoil of the growing criticism surrounding his friend and ministry partner. He mourns for what has taken place but eventually leaves to start a new church with other leaders. As so often happens when leaders fall, we are quick to grab a shovel instead of climbing into the hole with them.

The greater benefit of this movie for a Christian and especially leaders in a church is understanding how poorly a wandering shepherd is often handled. In Pearson’s case, his elevation as a “rising star” and “celebrity pastor” throw this into sharper relief. Instead of being treated with an ounce of regard, once he fails to recant he is ostracized and vilified. Congregants try to pray for his wife in the grocery store to have the spirit of the devil driven out of him. His mentor’s son goes on national television to denounce him and his peers essentially call him to a conference as a “speaker” when he is actually being put on trial. At no point is care taken to view him as someone in error deserving of love, friendship, and care. He is left to hang while passers-by ignore, mock, and insult him.

Yes, as shepherds of the flock of Christ, pastors are held accountable for those people and their teaching. But why must it come at the expense of their God-given humanity? In a world where a meth dealer, a serial killer, and a philandering, drunken outcast are some of the most beloved characters in TV history, is it possible a false teacher could be looked on with empathy and compassion? We have done so for belligerent, prideful, sexually immoral, and willfully sinful leaders. We don’t minimize the sin or it’s earthly and spiritual consequences, but we do maximize grace. Come Sunday begs us to consider these questions for a wandering shepherd. My hope and prayer are, as a human and a pastor, if myself or anyone I know wanders from the truth, there would be hard truth and tons grace to carry a heretic back into the flock.

Pingback: #169 – Coming Sunday, Ira Glass, and a Loving God | Reel World Theology