Review| Captain Fantastic

Being a father is frequently the most rewarding part of my life, but it is equally and often as terrifying as it is fulfilling. On the one hand, I am given a task of eternal significance, to love and care for a human person, made in God’s image, from a child to a fully functioning adult. On the other hand, I must accomplish this important privilege while still experiencing the uncertainty and emotions of life. The complexities of raising children bring joy and pain, honor and scorn, humor and solemnity. However, the tenacious love forged between a father and child is an unbroken cord more durable than the paradoxical intricacies of parenting.

Being a father is frequently the most rewarding part of my life, but it is equally and often as terrifying as it is fulfilling. On the one hand, I am given a task of eternal significance, to love and care for a human person, made in God’s image, from a child to a fully functioning adult. On the other hand, I must accomplish this important privilege while still experiencing the uncertainty and emotions of life. The complexities of raising children bring joy and pain, honor and scorn, humor and solemnity. However, the tenacious love forged between a father and child is an unbroken cord more durable than the paradoxical intricacies of parenting.

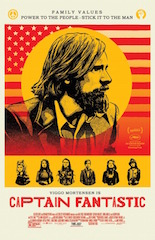

In director Matt Ross’ Captain Fantastic, Viggo Mortensen plays a father, Ben, raising six children in the backwoods of the Northwest United States. He and his wife, Leslie, have withdrawn from society to raise their kids to understand survival skills and pass on their ideals of “power to the people” and celebrating Noam Chomsky Day. It becomes clear, despite their election to withdraw from society, their family has suffered no ill effects on the surface. They play together, hunt together, laugh together, read together, and enjoy one another’s company like few modern families do.

Their rigorous mental and physical life is upended rather suddenly when the narrative turns to Leslie. She has been gone from their wilderness home at a hospital close to her parents in New Mexico for many months with an unexplained illness. When Ben ventures into town to get an update and talk to his wife, his sister-in-law tearfully reveals she killed herself.

Ross skillfully sets up the dramatic tone for the first two-thirds of the movie in the next scene. Revealing Ben’s attitude towards hardship and emotion, he gathers his children together and stoic manner tells them their mother is dead. While a lot of filmmakers would be tempted to cut away to music or cut the scene short to build dramatic tension as children tearfully grieve, Ross does no such thing. Evoking Ben’s psyche and unvarnished reassurances that Leslie’s death, “changes nothing,” the scene holds as the children hold one another and cry out in fresh, unbound pain. When Rellian, the middle son, howls in rage, grabs a hunting knife, and wildly stabs at a wood post, the only thing Ben can do is let him until his rage has passed. In a foreshadowing of later events, Rellian screams, “You killed her!” Mortensen plays his part unflinchingly and you sense Ben’s pain without a single uttered word as he embraces his son.

Mortensen’s performance is the greatest strength of this film. He supplies the movie with a lively gusto and intelligent warmth. The movie’s tone teeters on the same precipice a movie like Me, Earl, and the Dying Girl did last year. In that movie, the story came off as incredibly disingenuous and painfully smug. Likewise, Ben’s family’s incredible intelligence coupled with their “stick it to the man” brand of socialism could easily read smug and grate on audiences. However, Mortensen rescues the movie at multiple junctures with his balanced performance as a funny, intelligent, yet flawed father.

Going a bit against type, he is funny in a rebellious, matter-of-fact way around others, his in-laws for example, but also in his sober, idealistic observations about Western culture. Likewise, his kids see modern culture the same way aliens might view humanity as a whole. The game doesn’t run when they hunt, the people are all fat, and other kids find joy in pop culture escapism and video games. Their father has taught them well, but it has done little to prepare them for life outside their idealistic wilderness haven.

As the family makes it to his wife’s funeral in New Mexico, Ben’s carefully controlled world begins to crumble. His failure to take care of his wife when she was sick exposes his inability to lovingly connect with his children or have their best interests in mind. His survivalist and humanistic ideals are a common human response to bring order to chaos. It is his attempt to hold on to the parts of life he has no control over. But it is not a miraculous circumstance or a feel good decision that changes Ben’s heart, but a commitment to repentance and unconditional love.

When Ben owns up to how he has failed his family, he is a broken man. He leaves his family and heads to a gas station bathroom where he shaves his beard and cuts his hair symbolizing he is a new man. But it is not his love for his children that rescues him, but it is his children’s love of their father. He left them a broken, contrite man. They return to him with outstretched arms. It’s a moving picture of the unequivocal love of family that took this movie from pretty good to great. While some might find the movie insufferable, I saw true beauty in those final moments of familial commitment to one another.