Review| Bridge of Spies

This is a year for spy films—Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, Kingsman: The Secret Service, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and the forthcoming Spectre— and legendary director Steven Spielberg joins the fold with his highly anticipated Bridge of Spies. Starring Tom Hanks, written in part by the Coen Brothers, and scored by Thomas Newman, the film is a veritable smorgasbord of filmmaking talent. But does it—can it—live up to all the hype?

This is a year for spy films—Mission Impossible: Rogue Nation, Kingsman: The Secret Service, The Man from U.N.C.L.E., and the forthcoming Spectre— and legendary director Steven Spielberg joins the fold with his highly anticipated Bridge of Spies. Starring Tom Hanks, written in part by the Coen Brothers, and scored by Thomas Newman, the film is a veritable smorgasbord of filmmaking talent. But does it—can it—live up to all the hype?

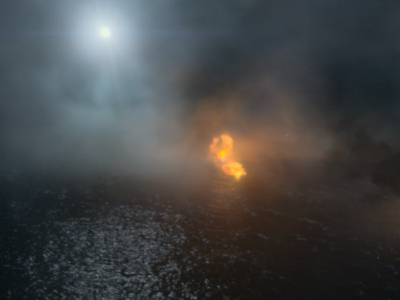

Spielberg’s Cold War tale begins with a lengthy sequence of near dialogue-free action. We watch Rudolf Abel (Mark Rylance), a suspicious looking individual, as he moves about town painting landscapes and collecting information from underneath park benches. Abel finds himself being shadowed by American agents, and he is soon taken into custody and accused of espionage crimes. Enter James Donovan (Tom Hanks), the archetypal Spielberg protagonist, an affable, affluent man who always knows the right thing to do and has absolutely zero qualms about getting it done. As a reputable insurance lawyer, Donovan is saddled with the task of defending Abel in court; and in spite of the fact that doing so will make him the object of public ridicule and potentially put his family in danger, Donovan is up to the task. He plans to defend Abel to the best of his ability. On the opposite side of the world, Francis Gary Powers (Austin Stowell), an American spy pilot who is shot down and apprehended in Russian territory, finds himself in a situation strikingly similar to that of Abel, which intensifies the conflict between the two nations.

Bridge of Spies is beautifully shot and boasts some masterfully executed visual doubling that elicits comparisons between the two rival nations, the United States and the Soviet Union. Indeed, the narrative is set up to explore the idea that perhaps we Americans are not as different from our enemies as we would like to think. In this sense then, although Bridge of Spies adopts the trappings of a Cold War film, it is actually poised to speak to the current political climate, which is perhaps as rife with fear-fueled rhetoric as was post-WWII America. Moreover the film has much to say that resonates with a Christian understanding of the world; its call to love both neighbor and enemy is one that desperately needs to be heard and heeded, and much of it seeks to uproot latent culturalism and ethnocentrism. Bridge of Spies is an ambitious film to be sure.

Bridge of Spies is beautifully shot and boasts some masterfully executed visual doubling that elicits comparisons between the two rival nations, the United States and the Soviet Union. Indeed, the narrative is set up to explore the idea that perhaps we Americans are not as different from our enemies as we would like to think. In this sense then, although Bridge of Spies adopts the trappings of a Cold War film, it is actually poised to speak to the current political climate, which is perhaps as rife with fear-fueled rhetoric as was post-WWII America. Moreover the film has much to say that resonates with a Christian understanding of the world; its call to love both neighbor and enemy is one that desperately needs to be heard and heeded, and much of it seeks to uproot latent culturalism and ethnocentrism. Bridge of Spies is an ambitious film to be sure.

Ultimately, however, Bridge of Spies falls short of its lofty goals and fails to offer up any lasting and meaningful kind of self-reflective critique of American society. In spite of its best efforts, it ends up promoting the very sort of American exceptionalism it professes to condemn. One reasons Bridge of Spies underwhelms is because it is so diametrically opposed to the moral ambiguity that characterizes the best Cold War cinema. Consider, for instance, Marty Ritt’s internally tortured Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965). Leamas is the opposite of Spielberg’s Donovan in almost every way; he is unsure of himself, unsure of the identity of the enemy, and even unsure as to whether or not he is on the right side of the affair. This kind of le Carréian pessimism is a key component in using Cold War narratives to speak to present affairs (after all, the cultural climates are not that dissimilar). Spielberg, however, is the anti-le Carré, and refuses to deal in the shady morality and shadowy world of espionage. Certainly there are some scenes that land home and make the audience consider the “other side” of things, but Spielberg is also quick to remind us that we don’t torture our enemies and we have Tom Hanks; so we can never truly be as bad as the pesky Russians. Although it desperately wants to acknowledge that America is far from perfect, Bridge of Spies ends up affirming that even if that much is true, that we are even aware of the fact is just about enough to absolve us of our sins. It is simply good ol’ American exceptionalism in sheep’s clothing.

Ultimately, however, Bridge of Spies falls short of its lofty goals and fails to offer up any lasting and meaningful kind of self-reflective critique of American society. In spite of its best efforts, it ends up promoting the very sort of American exceptionalism it professes to condemn. One reasons Bridge of Spies underwhelms is because it is so diametrically opposed to the moral ambiguity that characterizes the best Cold War cinema. Consider, for instance, Marty Ritt’s internally tortured Alec Leamas in The Spy Who Came in from the Cold (1965). Leamas is the opposite of Spielberg’s Donovan in almost every way; he is unsure of himself, unsure of the identity of the enemy, and even unsure as to whether or not he is on the right side of the affair. This kind of le Carréian pessimism is a key component in using Cold War narratives to speak to present affairs (after all, the cultural climates are not that dissimilar). Spielberg, however, is the anti-le Carré, and refuses to deal in the shady morality and shadowy world of espionage. Certainly there are some scenes that land home and make the audience consider the “other side” of things, but Spielberg is also quick to remind us that we don’t torture our enemies and we have Tom Hanks; so we can never truly be as bad as the pesky Russians. Although it desperately wants to acknowledge that America is far from perfect, Bridge of Spies ends up affirming that even if that much is true, that we are even aware of the fact is just about enough to absolve us of our sins. It is simply good ol’ American exceptionalism in sheep’s clothing.

In spite of its failure to function as a thoughtful social commentary, Bridge of Spies is an entertaining enough flick to be sure. As always, Hanks is a real pleasure to watch. In the end, its worst crime is not that it is outright bad, but that it is simply unremarkable and unexceptional.

Pingback: #079 – Bridge of Spies and Historical Allegories | Reel World Theology