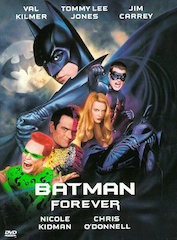

Review| Batman Forever

Riddle me this, riddle me that, what happened to the dark, gothic bat? Quite simply, I did. Looking back now it might seem like a huge leap to go from the brooding, bleak noir tones of Tim Burton’s Batman and Batman Returns to the glitzy, light-hearted campiness of Batman Forever, but at the time, it made complete sense to me. That’s because at the time I was 10 years old and wanted a Batman film my parents would let me see in the theater. Millions of other kids and parents felt the same way, and since money talks, a new vision was born for the bat.

Riddle me this, riddle me that, what happened to the dark, gothic bat? Quite simply, I did. Looking back now it might seem like a huge leap to go from the brooding, bleak noir tones of Tim Burton’s Batman and Batman Returns to the glitzy, light-hearted campiness of Batman Forever, but at the time, it made complete sense to me. That’s because at the time I was 10 years old and wanted a Batman film my parents would let me see in the theater. Millions of other kids and parents felt the same way, and since money talks, a new vision was born for the bat.

I still get the butterflies of excitement with the grandiose opening of this film, remembering being there on opening weekend and loving every minute of this movie as a kid. The campiness doesn’t quite hold up these days. Batman standing beside the Batmobile in the shadows of the Batcave and deadpanning that he’ll “get drive-thru” wasn’t even a balanced aesthetic at the time and in the modern movie, climate sits about as well as all of those incessant James Bond puns. Yet surprisingly, the movie as a whole does still hold up pretty well today for the same reasons that Batman the character has held up for over 75 years.

Most of the live action Batman films, in general, have suffered from the same issue- they’re not really about Batman. Batman/ Bruce Wayne is a complex character worthy of deep exploration, yet the movies have been burdened by saddling his story with a villain arc that often comes across as more interesting. Jack Nicholson’s Joker, Michelle Pfeiffer’s Catwoman, and Jim Carrey’s Riddler are far more interesting on screen than Batman is in any of the respective films. It wasn’t until Batman Begins that we truly got a film about Batman. However, once you dig past the neon color palette and the corny one-liners, Batman Forever gives us a more tangible examination of Batman than its predecessors.

Riddler: “I will help you solve the greatest riddle of all- the mother of all riddles- who is Batman?”

What a grand riddle indeed. Bruce Wayne himself doesn’t even really know who he nor Batman really is. This internal struggle of the Bruce Wayne character has followed him through all of his comics, cartoons, and films. Naturally, it’s going to foil the plans of the villains so obsessed over it. But in the meantime, it provides us with the journey that keeps us coming back to Batman films. We all want to know the answer to the riddle “who is Batman” because it helps us to better understand the riddle of who we are.

Oscar Wilde: Man is least himself when he talks in his own person. Give him a mask, and he will tell you the truth.

This movie tackles the Batman identity crisis head on, albeit a little ham-handedly. Two-Face is the physical embodiment of warring natures, the Riddler is the psychological embodiment, and Batman is both physical and mental. Bruce and Dr. Chase Meridian dance around the idea, yet never get to explore it because they just really needed her character to be obsessed with leather for some reason. Along comes Robin to pretty much ruin the thematic structure, but perhaps it can be said he gave it a good college try to muster up some duality. Nonetheless, the question is posed- is the mask of Batman a more truthful nature than the face of Bruce Wayne?

We all have warring natures, though of course not all are as outwardly displayed as Batman’s. We are defined by what we do with them (yes that’s my shout out to Batman Begins), and it is precisely this external battle with nature that fascinates us with these stories. Bruce Wayne defies his warring selves outright and turns it into good. It is a hope for us as we face our own internal battles.

Batman: “You see, I’m both Bruce Wayne and Batman, not because I have to be, now, because I choose to be.”

Superman is often displayed as a model of Christ. Batman, to me, is more of a model of a Christian. You can use the sacrificial savior image for him, but it doesn’t work as much as with Supes. The Christian believes in two natures- sinful and non-sinful, flesh and spirit. We believe that Christ has set us free from sin and conquered our sinful nature for us. It is something we are incapable of doing on our own, which is partly why we battle with it despite our salvation. While it’s an imperfect parallel, Batman provides us an image of how our sinful nature doesn’t have to control us. Batman does well despite the anger and sorrow that haunts Bruce Wayne. We can debate if beating up bad guys is exactly “good” or not another time, but it’s his version of good.

The heart is fickle, though. We want to be/ do good but we want to indulge ourselves. We know sin doesn’t enslave us, yet we pick up the chains. The war continues. You need only look at our movie tastes as proof. Nothing is ever good enough for very long. But as we approach our fourth film adaptation of Batman, we understand that while the visuals change, we keep coming back because of what is inherent to us all. We’ll probably keep watching Batman battle his natures for as long as we’ll be battling ours. Which is to say, forever.