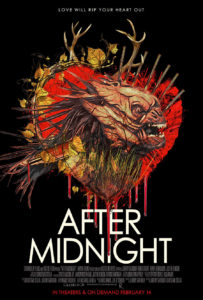

Review| After Midnight (2020)

Jeremy Gardner is one of those actors that is instantly recognizable and yet many may not know—unless, like me, you are entrenched in the larger horror community—that he is a triple threat when it comes to films. After Midnight is his third directorial feature after his debut in 2012 with the DIY zombie flick, The Battery, and the crowdsourced survival comedy in 2015, Tex Montana Will Survive! However, his talents extend into writing and directing as well. Each of these films was directed by Gardner and his partner, Christian Stella, and were also written by him as well. It is no surprise that there is a lot of crossover between his films and the indie horror flicks of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorehead (Resolution, Spring, and The Endless). Gardner shows up in Benson and Moorehead’s Spring and Benson shows up in After Midnight along with indie film darling, Brea Grant.

Jeremy Gardner is one of those actors that is instantly recognizable and yet many may not know—unless, like me, you are entrenched in the larger horror community—that he is a triple threat when it comes to films. After Midnight is his third directorial feature after his debut in 2012 with the DIY zombie flick, The Battery, and the crowdsourced survival comedy in 2015, Tex Montana Will Survive! However, his talents extend into writing and directing as well. Each of these films was directed by Gardner and his partner, Christian Stella, and were also written by him as well. It is no surprise that there is a lot of crossover between his films and the indie horror flicks of Justin Benson and Aaron Moorehead (Resolution, Spring, and The Endless). Gardner shows up in Benson and Moorehead’s Spring and Benson shows up in After Midnight along with indie film darling, Brea Grant.

While I have largely been lukewarm on Gardner’s output up until After Midnight, I have respected his craft and the spirit that his films embody. After Midnight maintains that spirit and finally finds the right story and technical approach that made me fall hard for this film. Like film critic Mark Kermode always says, Jaws is a movie about sharks that is not actually about sharks and this rubric is often descriptive of the best of the horror genre. This film then is a creature feature that is not actually about the thing that goes bump in the night on the edges of the setting’s orchard. Gardner plays Hank, a small-town guy, who has never been concerned with the wider world outside of his hometown. His wife (Brea Grant), Abby, on the other hand, is suffocating in this small town and her husband’s small-town mentality. She leaves unexpectedly and Hank finds himself confused as to why she left, where she went, and in the midst of this mystery begins seeing a creature stalking his old farmhouse.

The film smartly interrogates assumptions around the supposed unimportance of small towns in the wider world. It also interrogates the isolative mentalities that often accompany the inhabitants of those towns in the midst of threats. The film finds Hank’s world being expanded both abstractly when it comes to loving his wife and taking her needs on himself and physically when coming in contact with a creature that is not ever seen throughout most of the film. When we finally see it in flesh and blood, it comes at Hank’s most vulnerable point in the film. And the finally note that the film lands on is what makes the film so surprisingly warm is that, yes, vulnerability invites the monsters in to maul us, but if we survive their attacks, our connection with those we love will only be more solidified in the process.

The film smartly interrogates assumptions around the supposed unimportance of small towns in the wider world. It also interrogates the isolative mentalities that often accompany the inhabitants of those towns in the midst of threats. The film finds Hank’s world being expanded both abstractly when it comes to loving his wife and taking her needs on himself and physically when coming in contact with a creature that is not ever seen throughout most of the film. When we finally see it in flesh and blood, it comes at Hank’s most vulnerable point in the film. And the finally note that the film lands on is what makes the film so surprisingly warm is that, yes, vulnerability invites the monsters in to maul us, but if we survive their attacks, our connection with those we love will only be more solidified in the process.

I did not go into this film expecting it to have such a resonant tone for our current cultural climate, but perhaps its message (both the real and metaphorical elements) is exactly what we as citizens of this country need more of right now: vulnerability. As the new Jason Isbell song, “Be Afraid” states, “Be afraid. Be very afraid. Do it anyways.”