Review| 13 Minutes to the Moon and an Echo of a Greater Mission

Most episodes of 13 Minutes to the Moon begin with the tell-tale staticky buzz-whine of Apollo’s radio background noise and the iconic high-pitched beep of a Quindar tone. Like the Apollo 11 mission itself, the podcast is deliberate, well-planned, and a remarkable—even beautiful—achievement. It always has a goal. It always makes you think. And it’s always a too-short ride to something we think we know a lot about, only to discover we know very little.

Most episodes of 13 Minutes to the Moon begin with the tell-tale staticky buzz-whine of Apollo’s radio background noise and the iconic high-pitched beep of a Quindar tone. Like the Apollo 11 mission itself, the podcast is deliberate, well-planned, and a remarkable—even beautiful—achievement. It always has a goal. It always makes you think. And it’s always a too-short ride to something we think we know a lot about, only to discover we know very little.

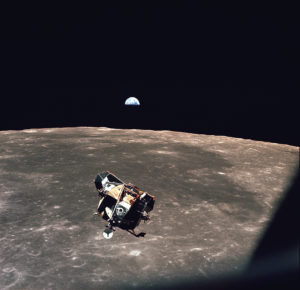

While last year’s fantastic First Man focused on the life of Neil Armstrong himself, and this year’s stunning Apollo 11 takes a lingering look at the mission as a whole, Kevin Fong’s 13 Minutes to the Moon uses the final thirteen white-knuckled minutes of the descent to the lunar surface as a lens through which to see the entire U. S. Space Program in the 1960s. The podcast is gripping and intimate, beautifully produced and lovingly crafted. It’s worth every second of the experience. I’ve been a NASA fanboy for my entire life, and this is my new favorite way to relive the most audacious scientific mission in history.

But Apollo 11’s mission wasn’t just a scientific expedition. It wasn’t just a political victory to put America ahead of the Soviet Union.

But Apollo 11’s mission wasn’t just a scientific expedition. It wasn’t just a political victory to put America ahead of the Soviet Union.

It was an echo of God’s mission for His people.

13 Minutes to God

God wants us to know Him.

In 13 Minutes to the Moon, much is made of the unknowns surrounding space travel to the moon. Few things about the program were certain, but one thing was clear: the goal. Given by President Kennedy, the goal was clear and detailed: before the decade is out, send a man to the surface and return him safely to Earth. The entire Apollo program is predicated on this goal.

And the entire Christian life is predicated on a given goal: God wants us to know Him.

That might be a surprise to some, given the general air of mystery that seems to surround God; but that’s from us, not from Him. On the contrary, He intends for us to know Him, and He puts stars in the sky to woo us into pursuing that knowledge: “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork,” David insists in the Psalms. “You have set your glory above the heavens…When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?”

Indeed, stellar bodies are used as superlative comparisons to God regularly in the Bible: the Sun, of course, as a giver of light; the stars, as innumerably complex and heart-wrenchingly gorgeous; and the moon as a firm, faithful, forever-established guardian of even our darkness.

Indeed, stellar bodies are used as superlative comparisons to God regularly in the Bible: the Sun, of course, as a giver of light; the stars, as innumerably complex and heart-wrenchingly gorgeous; and the moon as a firm, faithful, forever-established guardian of even our darkness.

In my mind, God’s message is clear: “know Me! I’ve given you the Bible, I’ve given you My son, and I’ve given you the night sky so that you would understand and know me.”

This makes Apollo 11 more than just a scientific mission: it’s also a theological one.

13 Minutes to Science

Johannes Kepler held a very high view of the theological importance of scientific study. He thought that his work was nothing more than “merely thinking God’s thoughts after him. Since we astronomers are priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature, it benefits us to be thoughtful, not of the glory of our minds, but rather, above all else, of the glory of God.”

Science isn’t just a way to learn more about the universe. In learning about creation, we learn about the Creator; in ways subtle and grand, we see the fingerprints of God and understand more about the choices He made. It’s why He made science, as Paul E. Miller contends in his book, A Praying Life: “If [a] stream is a result of accidental natural forces, then you just see water, rocks, and dirt. If God equals the stream, then you worship the stream god, not the creator of the stream. But if God created the stream, then wonder and curiosity naturally flow into study.”

Science isn’t just a way to learn more about the universe. In learning about creation, we learn about the Creator; in ways subtle and grand, we see the fingerprints of God and understand more about the choices He made. It’s why He made science, as Paul E. Miller contends in his book, A Praying Life: “If [a] stream is a result of accidental natural forces, then you just see water, rocks, and dirt. If God equals the stream, then you worship the stream god, not the creator of the stream. But if God created the stream, then wonder and curiosity naturally flow into study.”

With science, we can know more about who God is. More than that, we will know more about who God is. It is inevitable.

Knowing that the universe is infinite, for instance, gives us a more full understanding of the breadth of the Mind that created and keeps it; giving a new depth to Paul’s insistent meditation in Romans: “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!”

Knowing the incomprehensible alien-ness of the creatures at the bottom of the ocean gives new meaning to the prophet Micah’s reassurance that God “will tread our sins underfoot and hurl all our iniquities into the depths of the sea.” We won’t even recognize them anymore. They’ll be far from us, disconnected and alien.

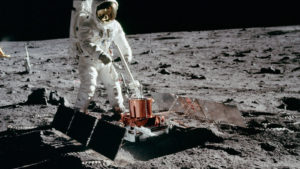

And knowing that we can get to the moon reminds us of the power God has vested in His creation via common grace: together, step by ponderous step, we can research our way to the moon. 13 Minutes to the Moon gives a clearer look at how many people it took to make those incremental steps that led to Neil Armstrong’s famous “small step.”

And knowing that we can get to the moon reminds us of the power God has vested in His creation via common grace: together, step by ponderous step, we can research our way to the moon. 13 Minutes to the Moon gives a clearer look at how many people it took to make those incremental steps that led to Neil Armstrong’s famous “small step.”

It was a mission of discovery that drove hundreds of thousands of people. And it was an echo of God’s mission.

13 Minutes to God’s Mission

The endeavor to get to the moon was a microcosmic echo of God’s plan. If God wants us to know Him, and science is a way God has given us to know Himself, then the moon mission was a part of God’s mission; but it’s also an echo of the greatest and most intimate way God provided for us to know Him.

13 Minutes to the Moon shows how deliberate and planned, yet breakneck and runaway, every second of the Apollo program was, and we get more than one close-up view during the final thirteen minutes: for instance, with a 1202 program alarm buzzing on the Landing Module’s navigation computer, Jack Garman had to rely on a set of deliberate plans which Gene Kranz had forced him to make mere days before to decide whether the landing could continue or not.

This echo is sharpest when we look at the prophecies predicting Jesus’ birth, life, and death. Hundreds of years before He came, God’s mission was planned out deliberately. Step by step, things occurred in the exact order He had foreseen. Jesus’ mission to land on our world was planned out to the most minute detail; and when He ascended back into heaven, Jesus’ mission became our own. Let people see Him; show people how God can be known through Jesus. At the point it fell upon us, it began to feel like a runaway rocket; but as insecure as the ride can feel, we can be certain in the ride itself.

The echo of God’s mission in the story of the lunar landing gives us just a taste; enough to see that the Lord is good, that His mission is so that we can know Him in eternity.

13 Minutes to the Moon Landing

If you’re even tangentially interested in space travel, the moon landing, science, the 1960s, or humans, I cannot recommend Kevin Fong’s podcast 13 Minutes to the Moon highly enough. It’s superb. But more than just a mark of excellence, it shows us a glimpse of God’s own mission to land here as Jesus, for all mankind.

When we go on to new scientific discoveries, we’ll be learning more about God. When we look back on the moon mission, we’ll be seeing an echo of God’s. But no matter where we look, we can be sure: God wants us to know Him. It won’t be easy. It will require deliberate steps and bold action. It will feature frantic, breakneck speed and thoughtful contemplation. We can’t do it alone. But we are “go” for launch. All engines running.

Review| 13 Minutes to the Moon and an Echo of a Greater Mission

July 20, 2019David Atwell Commentary, Documentary, Historical, review0

While last year’s fantastic First Man focused on the life of Neil Armstrong himself, and this year’s stunning Apollo 11 takes a lingering look at the mission as a whole, Kevin Fong’s 13 Minutes to the Moon uses the final thirteen white-knuckled minutes of the descent to the lunar surface as a lens through which to see the entire U. S. Space Program in the 1960s. The podcast is gripping and intimate, beautifully produced and lovingly crafted. It’s worth every second of the experience. I’ve been a NASA fanboy for my entire life, and this is my new favorite way to relive the most audacious scientific mission in history.

It was an echo of God’s mission for His people.

13 Minutes to God

God wants us to know Him.

In 13 Minutes to the Moon, much is made of the unknowns surrounding space travel to the moon. Few things about the program were certain, but one thing was clear: the goal. Given by President Kennedy, the goal was clear and detailed: before the decade is out, send a man to the surface and return him safely to Earth. The entire Apollo program is predicated on this goal.

And the entire Christian life is predicated on a given goal: God wants us to know Him.

That might be a surprise to some, given the general air of mystery that seems to surround God; but that’s from us, not from Him. On the contrary, He intends for us to know Him, and He puts stars in the sky to woo us into pursuing that knowledge: “The heavens declare the glory of God, and the sky above proclaims his handiwork,” David insists in the Psalms. “You have set your glory above the heavens…When I look at your heavens, the work of your fingers, the moon and the stars, which you have set in place, what is man that you are mindful of him, and the son of man that you care for him?”

In my mind, God’s message is clear: “know Me! I’ve given you the Bible, I’ve given you My son, and I’ve given you the night sky so that you would understand and know me.”

This makes Apollo 11 more than just a scientific mission: it’s also a theological one.

13 Minutes to Science

Johannes Kepler held a very high view of the theological importance of scientific study. He thought that his work was nothing more than “merely thinking God’s thoughts after him. Since we astronomers are priests of the highest God in regard to the book of nature, it benefits us to be thoughtful, not of the glory of our minds, but rather, above all else, of the glory of God.”

With science, we can know more about who God is. More than that, we will know more about who God is. It is inevitable.

Knowing that the universe is infinite, for instance, gives us a more full understanding of the breadth of the Mind that created and keeps it; giving a new depth to Paul’s insistent meditation in Romans: “Oh, the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!”

Knowing the incomprehensible alien-ness of the creatures at the bottom of the ocean gives new meaning to the prophet Micah’s reassurance that God “will tread our sins underfoot and hurl all our iniquities into the depths of the sea.” We won’t even recognize them anymore. They’ll be far from us, disconnected and alien.

It was a mission of discovery that drove hundreds of thousands of people. And it was an echo of God’s mission.

13 Minutes to God’s Mission

The endeavor to get to the moon was a microcosmic echo of God’s plan. If God wants us to know Him, and science is a way God has given us to know Himself, then the moon mission was a part of God’s mission; but it’s also an echo of the greatest and most intimate way God provided for us to know Him.

13 Minutes to the Moon shows how deliberate and planned, yet breakneck and runaway, every second of the Apollo program was, and we get more than one close-up view during the final thirteen minutes: for instance, with a 1202 program alarm buzzing on the Landing Module’s navigation computer, Jack Garman had to rely on a set of deliberate plans which Gene Kranz had forced him to make mere days before to decide whether the landing could continue or not.

This echo is sharpest when we look at the prophecies predicting Jesus’ birth, life, and death. Hundreds of years before He came, God’s mission was planned out deliberately. Step by step, things occurred in the exact order He had foreseen. Jesus’ mission to land on our world was planned out to the most minute detail; and when He ascended back into heaven, Jesus’ mission became our own. Let people see Him; show people how God can be known through Jesus. At the point it fell upon us, it began to feel like a runaway rocket; but as insecure as the ride can feel, we can be certain in the ride itself.

The echo of God’s mission in the story of the lunar landing gives us just a taste; enough to see that the Lord is good, that His mission is so that we can know Him in eternity.

13 Minutes to the Moon Landing

If you’re even tangentially interested in space travel, the moon landing, science, the 1960s, or humans, I cannot recommend Kevin Fong’s podcast 13 Minutes to the Moon highly enough. It’s superb. But more than just a mark of excellence, it shows us a glimpse of God’s own mission to land here as Jesus, for all mankind.

When we go on to new scientific discoveries, we’ll be learning more about God. When we look back on the moon mission, we’ll be seeing an echo of God’s. But no matter where we look, we can be sure: God wants us to know Him. It won’t be easy. It will require deliberate steps and bold action. It will feature frantic, breakneck speed and thoughtful contemplation. We can’t do it alone. But we are “go” for launch. All engines running.

Written by David Atwell

David Atwell (@ilinamorato) is the managing editor at Reel World Theology, with a generally positive attitude about culture and film. He developed a passion for redeeming culture in college, and began to talk about it incessantly with everyone until they finally convinced him to write about it on the internet. He's Natalie's husband, a father of three, and a member of a church that's also an art gallery. When he's not doing any of the things already mentioned, he's probably being a stereotypical geek. You can also find him on Letterboxd or at RedeemingCulture.com.

Related Articles

WandaVision: Grief on the Small Screen (RWT Podcast S8E5 + Bonus Episode!)

March 18, 20220

Free Guy: Liberty to the NPCs (RWT Podcast S8E4)

February 26, 20220

Encanto: Mirabel’s Miracle (RWT Podcast S8E3)

February 13, 20220