Oh! The Horror… | of Our Grief-Stricken Thoughts

Reader, be warned, there be spoilers ahead…

Reader, be warned, there be spoilers ahead…

There are all sorts of monsters that lurk in dark recesses. Some are fictional—lingering between the pages of a book and the flickering celluloid of films—while others are imaginary but are given psychical power by us as they take residence in our closets, under our beds and in the dark corners of our rooms; not to mention the actual monsters in the world that look like you and me who do horrifying acts of evil. But there is still another kind of monster, one that relentlessly haunts our existence and bides its time on the edges of our consciousness waiting for us to acknowledge it. This monster is a presence that every human being will come to know, intimately, at some point in their life: grief.

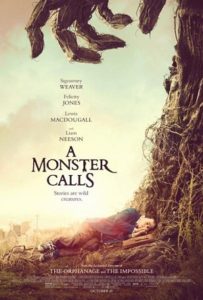

A Monster Calls is about a boy named Conor O’Malley whose mother is slowly perishing from cancer. Amid this very intimate and painful form of suffering is the appearance of a giant monster that morphs out of a Yew tree when he comes to visit Conor at 12:07 each night. On the first night of its appearance the monster tells Conor it will tell him three stories and, at the end of the third story, Conor must tell the monster a fourth story, a true story. This story will uncover “Conor’s truth.” Within the first fifteen minutes of the film, the ending is clearly telegraphed to the audience. There is no doubt about the outcome of the mother’s fight as she goes in and out of treatment. We are fully aware of what dragons will lay ahead.

What the audience may not expect—unless they had read the book before seeing the movie—is the content of “Conor’s truth” and how that truth places this film above the sentimentality of films like Collateral Beauty and the emotional manipulation of films like The Notebook. Conor’s truth is something that people who have suffered alongside loved ones living through long, unabated fights for life in the face of ravaging diseases like cancer or Parkinson’s know and fear. It is the thought that crosses their mind that says they wish it would all end and that the person they love would finally die. A thought that comes from a place of exhaustion and anger and complete loss of any illusion of control.

The days of hiding a tear-streaked face emerging from the darkened cover of the cinema are long gone. To put it simply, I was a basket case by the time the credits rolled because the film found a way to authentically and sincerely take me through a beautiful, creative and highly cathartic trip through the emotional hell that is watching a loved one slowly die. It rang true by the time the film faded to black because I could honestly say one thing:

I, too, am Conor O’Malley.

As I see my own father lose his faculties, his use of language, his ability to tell right from left, the impairment of his reading and counting, and the continual dissipation of his memories into the darkened void, there is a whisper that I dare not give voice too: I, too, wish it was over. I don’t want to see him succumb to a shell of himself because of Alzheimer’s. Death does seem better in the long run. These are terrifying thoughts to have when love is supposed to lift life up instead of death. But these thoughts are there in my head, rattling around. The monster of grief has a way of illuminating those thoughts for the sake of the survivors. If Conor O’Malley had never spoken that truth out loud, given them flesh, then he would have drowned in a sea of guilt and self-punishment.

As I see my own father lose his faculties, his use of language, his ability to tell right from left, the impairment of his reading and counting, and the continual dissipation of his memories into the darkened void, there is a whisper that I dare not give voice too: I, too, wish it was over. I don’t want to see him succumb to a shell of himself because of Alzheimer’s. Death does seem better in the long run. These are terrifying thoughts to have when love is supposed to lift life up instead of death. But these thoughts are there in my head, rattling around. The monster of grief has a way of illuminating those thoughts for the sake of the survivors. If Conor O’Malley had never spoken that truth out loud, given them flesh, then he would have drowned in a sea of guilt and self-punishment.

The three stories told by the monster to Conor during the film rely on a theme of grace during judgment and punishment. Each story leaves Conor baffled as to why characters were not straightforward in their goodness or badness and why characters were shown grace amidst wrongdoing. With each story, the monster is preparing the boy to come face to face with the very thoughts that accuse him and drive him to feel a dreadful guilt and judgment thereby keeping him from embracing the time he has with his mother. Conor learns that only grace and mercy frees people up to love appropriately and be present in the trenches of suffering within this broken world. Something that, as I have gotten older, I should know already and yet need to be reminded of repeatedly due to my own forgetfulness.

Some people may look at the language of the film (and the book, for that matter) as being problematic in its relativistic sound (“your truth”) and the seeming moral ambiguity of the stories being told. The latter complaint should be tossed out wholesale because one cannot simply read the details of the Bible as anything but morally ambiguous. It is only in the big picture that moral certainty comes into play: God is good, his creation is broken and sinful. However, this film is dealing with the reality of the world that all of us perceive in our own limited ways.

It is the former complaint that I could see having some teeth possibly. When I read the book, and saw the movie, I initially was taken aback by the wording of “your truth” or “Conor’s truth.” Christians are somewhat predisposed to being gun shy with such language (many times, understandably so), but there is an element of this grand narrative of redemption and grace that is specific to individuals or specific groups. Because we are limited in our understanding, vision, etc., our lives as we know them are “true” to us because we can’t see the woods for the trees. This doesn’t mean that God’s divine truth and plan are supplanted by our limited understanding of our own lives, but it does mean that all of us live per this functional form of truth we think we know about ourselves, our lives and how this universe works. We all look at it differently and that “truth” creates the framework in which we function. Sometimes our “truth” gets shattered by the monster of grief and suffering, among other forces which humans come in contact.

Conor’s “truth” before the end of the movie was something he operated by in his everyday life. But the monster came to supplant that “truth” with a higher truth from which Conor felt the judgment and guilt. However, Conor needed to voice it, incarnate it into his existence, make it part of his functional truth in order to understand how grace and mercy could possibly save him from that judgment and guilt.

Conor’s “truth” before the end of the movie was something he operated by in his everyday life. But the monster came to supplant that “truth” with a higher truth from which Conor felt the judgment and guilt. However, Conor needed to voice it, incarnate it into his existence, make it part of his functional truth in order to understand how grace and mercy could possibly save him from that judgment and guilt.

I, too, live life with a functional form of truth. As I watch my father slowly succumb to the disease that ravages him day in and day out, I have thoughts that I know I shouldn’t have because of the pain that is felt by my father, my family and myself. It is only when I voice those functional truths, give them flesh, that I can let them be supplanted by a higher and more perfect truth, one that seeks to forgive me, show me mercy and help me love my father better in the moment because of its content: grace. For it is grace, also, that God’s truth can be given to us and made functional by us in this world. Something that A Monster Calls speaks to in emotional depth with sincere tears and catharsis. So that we may recognize the mercy shown to the monsters that live in us all.

Pingback: #124 – A Monster Calls and A Better Truth | Reel World Theology