Oh! The Horror… | Of Making It Through The Film

“Movies can use transgressive topics and imagery toward great artistic resonance. They can also just use them for pure shock/novelty/boundary-pushing, which is where I’d group Serbian Film. That it comes from a country that’s spent decades deep in violent conflict, civil unrest, corruption and ethnic tensions makes it tempting to read more into the film than I think it actually offers—ultimately, it has as much to say about its country of origin as Hostel does about America, which is a little, but nothing on the scale its title suggests.” –Alison Wilmore

“A Serbian Film” refers both to Mr. Spasojevic’s movie and also, perhaps more directly, to the movie inside it, which Vukmir envisions as a transcendent expression of Serbia’s national identity. The framing tale, with its allusions to the Balkan wars of the 1990s and the greed and political corruption that followed, can thus be seen as a piece of corrosive social criticism, exposing a national psychology of sadism, misogyny and self-pity. That it may also be an example of those things is no contradiction.” –A. O. Scott

“I think the film is tragic, sickening, disturbing, twisted, absurd, infuriated, and actually quite intelligent. There are those who will be unable (or unwilling) to decipher even the most basic of ‘messages’ buried within A Serbian Film, but I believe it’s one of the most legitimately fascinating films I’ve ever seen. I admire and detest it at the same time. And I will never watch it again. Ever.” –Scott Weinberg

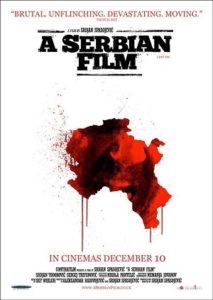

These three quotes sum up the range of critical feeling around Srđan Spasojević’s feature film debut, 2010’s A Serbian Film. I included these excerpts for a two reasons. First, I respect each one of these film critics equally and, second, though their final appraisal of the film may run the spectrum, they all seem to agree on one thing: this film is made for one time viewing only. They were right. Unlike viewers and critics upon its release back in 2010, I knew what I was getting myself into, but I did not know whether I would actually be able to finish the film if it was as bad as the descriptions promised. I did, however, finish all 104 minutes of the film. I am pretty sure that sums up the weaker elements of my nature: I’m just reckless enough to be morally compromised by a film.

These three quotes sum up the range of critical feeling around Srđan Spasojević’s feature film debut, 2010’s A Serbian Film. I included these excerpts for a two reasons. First, I respect each one of these film critics equally and, second, though their final appraisal of the film may run the spectrum, they all seem to agree on one thing: this film is made for one time viewing only. They were right. Unlike viewers and critics upon its release back in 2010, I knew what I was getting myself into, but I did not know whether I would actually be able to finish the film if it was as bad as the descriptions promised. I did, however, finish all 104 minutes of the film. I am pretty sure that sums up the weaker elements of my nature: I’m just reckless enough to be morally compromised by a film.

The basic narrative of the film follows an aging porn star, Milos, who is offered a part in a film and a sizable payment by a seemingly intelligent and unknown filmmaker who goes by Vukmir. What the film turns out to be, however, is less a by-the-numbers, low budget Serbian porn film and more something along the lines of a snuff film, a film that features actual violence, sexual degradation and death. Initially, Milos volunteers to star in the film and enacts the first couple of scenes of this film. However, as the set pieces and situations become more grim and violent, his willingness fades and he is drugged into submission. The worst third of the film finds much of the depravity shown in memories and tapes Milos watches after he wakes up from a drug-induced blackout.

There is a particularly sickening and gratuitous scene about midway through the film that would have caused many, if not most, to walk out of the film or turn off the TV. I admit I was shocked by the implication of the scene. Nothing was shown—thankfully—but the suggestion was enough. I probably should have turned the film off at that point, but I didn’t. I think this a question that I need to entertain for a minute: what is it that drives me to continue watching something that is intentionally and gratuitously cruel and nasty?

Is it bloodlust? Maybe, but I did not feel any catharsis in the blood that was shed before, during or after the sexual acts that were at the center of the film’s narrative. Was it titillation? Maybe, but I did not find any of the graphic and violent sexuality to invoke those base desires in me. Or was it a need to see the film’s conclusion in order to make sense of or justify myself in consuming the very images I just viewed? Maybe, but once again, I am not entirely sure that the ending gave a satisfactory justification to ease my conscience.

All that I came away with, really, was a vicarious implication in the crimes showcased in the film—for which the filmmakers were investigated, but not found guilty apparently.

The difficult part of this film is that it is technically well made with widescreen shots and better than average acting. If one wants to follow the line of reasoning that Spasojević offers for the making and meaning of the film, I think the trajectory and the ending of the film, on a very baseline narrative level, works. On one level, this could be taken as one very graphic metaphor about the nature of being a citizen of Serbia and how its women are degraded and its youth’s innocence is destroyed ultimately leading to a broken, corrupt nation and broken families and people.

The difficult part of this film is that it is technically well made with widescreen shots and better than average acting. If one wants to follow the line of reasoning that Spasojević offers for the making and meaning of the film, I think the trajectory and the ending of the film, on a very baseline narrative level, works. On one level, this could be taken as one very graphic metaphor about the nature of being a citizen of Serbia and how its women are degraded and its youth’s innocence is destroyed ultimately leading to a broken, corrupt nation and broken families and people.

However, I think the problem with A Serbian Film is not in setting out to be aggressive in portraying this metaphor, but in being too on the nose with how it chose to express its metaphor therefore blurring the lines between criticizing the Serbian government and society and becoming an example of the very thing it is attempting to critique. In other words, I think the film needed more restraint. Most other films that do not have such graphic imagery would have been criticized greatly for allowing such heavy-handed exposition within the boundaries of its script. This film got away with it because the viewers were probably too shell-shocked to notice. Good film persuades; it makes us feel its truth and meaning. It does not force feed it down our throats.

And this is ultimately the problem with the torture porn sub-genre of horror: it is more interested in the gore, sex and gruesomeness than it is in making the metaphor sink in under the audience’s skin. It is a cheap victory for these directors. If someone walks out of the film because of a significantly awful scene, the director commends himself on touching a nerve, but if the person, like me, makes it all the way through the film, the director prides himself on being able to subvert that person’s moral compass. He is able to indict them of their own moral hypocrisy. It’s a cut-rate catch-22, but a catch-22 nonetheless. One that I fully admit finding myself caught in by the act of viewing the film in the first place.

While I do not commend very much of the argumentation used in fundamentalist camps and some veins of mainstream evangelicalism for why people should not consume cultural products that feature heavy usage of violence and sexuality, I do think discernment is important. The jury is still out as to whether I was discerning enough in my decision to watch this film fully knowing what types of images I would be seeing. I will leave that up to my Christian brothers and sisters to decide.

While I do not commend very much of the argumentation used in fundamentalist camps and some veins of mainstream evangelicalism for why people should not consume cultural products that feature heavy usage of violence and sexuality, I do think discernment is important. The jury is still out as to whether I was discerning enough in my decision to watch this film fully knowing what types of images I would be seeing. I will leave that up to my Christian brothers and sisters to decide.

When the final credits roll after its nihilistic and tragic ending, A Serbian Film finds itself as the more extreme and graphic version of films like Cheap Thrills, Would You Rather? and 13 Sins. Some, if not all of these films, have their defenders, however I feel that those who celebrate those films should be careful in their judgment of A Serbian Film. They all are, after all, the same film even though their expressions of violence and sexuality are more acceptable, culturally, than those portrayed in A Serbian Film. While I must deal with a couple of images I’ll never be able to unsee, there is still a quiet voice rumbling around in the back of my head: maybe Spasojević was onto something after all and there is cinema much more morally insidious than A Serbian Film within the culturally-acceptable entertainment we consume and yet find in it no response of repulsion. Sounds like something right out of The Screwtape Letters.