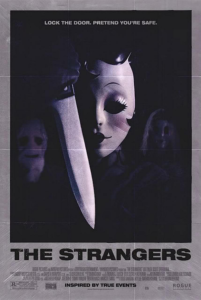

Oh! The Horror… | Of Breaking and Entering

To me it was about trying to ground the movie as much as possible so that the audience would believe that world, so we tried to find a house that your brother could have lived in and your father could have lived in, you could have grown up in. And the way we lit it, the colors we picked were all trying to find something comforting, trying to find something inviting, so that we could destroy that.

There are two parts to the architecture of these types of films. Most home invasion films concentrate on the narrative motion of the invasion thereby making the balance of the conceptual architecture a little unstable. Bryan Bertino sought to stabilize a sub-genre that had, on the whole, neglected to give particular care to the actual structural foundations of the narrative. In order to make an effective home invasion horror film, the home needs to be manifested clearly in the film. The spaces of the setting must be portrayed and given their own character in order for the presence of terror to realistically inhabit its architecture. Good home invasion films rely on precision comprehension of the spaces in which the action of the narrative is supposed to take place. It is here where I think The Strangers succeeds and fully illustrates both the setting and action of “home invasion.”

In the feature documentary, The Elements of Terror, included on the Blu-Ray edition of The Strangers, the film crew and director speak a lot about space, movement and terror as if they were integrated in such a way where failure to attend to one would lead to deficiencies in the other aspects. Bertino had a 70s-style Ranch house and floor plan–one of the most proliferated architectural styles in America–in mind for this film. He was adamant about the look and that it had a barn within a certain distance from the house and a driveway that, also, had a specific placement in orientation to the barn and house. The setting was significant to the movement of the narrative according to John Kretschmer, the production designer on the film:

In a classic kind of sense of a horror film, you often envision the house on the hill and you’re standing back and you’re seeing this place from the outside. This story is, I think, very much reversed, it takes place inside the house, looking out. Bertino built the architecture of the movie into the screenplay. I could tell what kind of house he had written this for. I could tell which way the hallway turned, where the bedrooms were, the kitchen, he had a very visual sense.

Bertino’s screenplay had a concrete visual sense of the spaces where the narrative action would take place. For the screenplay to transfer successfully onto celluloid, they had to find a house with a barn and a driveway that matched the exterior descriptions of the the screenplay. They found nearly the perfect on-site set. However, the interior of the actual house was too compact and claustrophobic for filming to take place within its walls, so they built the interior and its design within a warehouse not far away. This way the interior could fit the exact vision of the layout of the house in Bertino’s screenplay.

Every little piece of the set had a place within the movement of the film. Every space of that house in Bertino’s mind was explored and done in a way where the audience would probably be able to draw the basic layout of the interior of the house and the exterior of the house in relation to the barn and the driveway pretty easily after they had seen the film. By the time the central action of the home invasion begins, the audience knows the limits of Kristen McKay and James Hoyt’s movement within the house as the three masked intruders taunt and toy with them and eventually physically come after them. The audience, by this point, has an intimate sense of where they are and how the architecture of the house ends up starting to close in around them when the threat on the outside begins to move in.

Every little piece of the set had a place within the movement of the film. Every space of that house in Bertino’s mind was explored and done in a way where the audience would probably be able to draw the basic layout of the interior of the house and the exterior of the house in relation to the barn and the driveway pretty easily after they had seen the film. By the time the central action of the home invasion begins, the audience knows the limits of Kristen McKay and James Hoyt’s movement within the house as the three masked intruders taunt and toy with them and eventually physically come after them. The audience, by this point, has an intimate sense of where they are and how the architecture of the house ends up starting to close in around them when the threat on the outside begins to move in.

I had a discussion with my boss and good friend, Mason Rogers, architect and owner of Playa Design Studio in Amarillo, TX, about how space promotes or impedes movement. When I gave him the basic description of the layout of the ranch house and the design of the interior that is delivered in such detail within the world of The Strangers, he explained some of the subconscious and psychological factors going into how those spaces are visited and lived in.

Since the ranch house is such a prolific style in American architecture, Bertino has already set up a familiar setting, a home that a majority of people will subconsciously understand the second they walk into the house. There are public and private spheres.

In a ranch house floor plan the main entrance drives movement into the public spaces of the living and dining room where it opens into. Usually the long hallway, with bedrooms and bathrooms and hall closets shooting off from it, is just a turn away from the main entrance as well, but guests to a house know intuitively that the public spaces are where they are meant to go. As a guest, automatically going down the hallway, into the private space of the house without permission is a transgression, whether physical or subconscious, against the inhabitants of the house. This is why, in smaller homes where there isn’t a guest bathroom, one must confidently ask if they can use the restroom because, really, they are requesting whether the host will allow them to cross the barrier between public and private spaces.

The same psychological/subconscious elements work as well when Kristen and James are driven outside from their home. When the intruders stop taunting and physically transgress the safety of the home, Kristen and James are driven outside of their safe haven. Even non-murderous guests who enter the public and private spaces of a house without an invite become a threat. The home, perhaps more than any other place, including police stations, hospitals, etc., is, culturally, the last bastion of safety. If the home is no longer safe, there is a real sense of dread and displacement that happens, psychologically.

The way The Strangers sets up the outer world of this house is by making it a country town that acts more as a village that comes alive when owners come for seasonal retreats. Clearly, Kristen and James have come to his parents seasonal home out of season and have done so in the wee small hours of the morning, where darkness covers the country expanses that surround the wooded neighborhood thereby transforming open spaces in the daylight to suffocating darkness and disorientation at night. If Kristen and James were being attacked in the daylight, there would at least be a sense that they could escape and they could grab the attention of someone passing through.

The way The Strangers sets up the outer world of this house is by making it a country town that acts more as a village that comes alive when owners come for seasonal retreats. Clearly, Kristen and James have come to his parents seasonal home out of season and have done so in the wee small hours of the morning, where darkness covers the country expanses that surround the wooded neighborhood thereby transforming open spaces in the daylight to suffocating darkness and disorientation at night. If Kristen and James were being attacked in the daylight, there would at least be a sense that they could escape and they could grab the attention of someone passing through.

The shroud of darkness then creates a dichotomy: either be in the house with those who have transgressed not only the physical, but psychological boundaries, of the home, or go outside, into the dark, where, psychologically-speaking, one must contend with spaces where the blackness hides the unknown. Not even the barn is a sure bet, because who knows if there are more than three intruders and one is just waiting for them to rush into a space where there is no certainty of safety. Even their car becomes an unknown space. Maybe one of them broke into it and is lying i the backseat waiting. There is the safety of the home and then there is the compromised safety and unknown of the “outside.” So once the home becomes compromised, certainty becomes a luxury and terror becomes physically and psychologically manifest.

By making the setting detailed and effectively shot, Bertino has created spaces of terror and transgression within the world of The Strangers. By the end of the film, when Kristen yells “why are you doing this to us!” and the intruder called Dollface answers with “because you were home,” the audience feels the full brunt of that statement. Much like the many incarnations of the classic Joker villain in DC Comics, these intruders’ motivation is simply to watch the world burn and what drives their will is finding people in isolation who can be compromised by the intruders’ transgression of culturally-constructed spaces that our human psychology bases its spatial understanding of safety on. When these cultural constructs are deconstructed, like they are within the runtime of The Strangers, people become terrified by the revelation of their true status within a broken world: they are laid bare, no one is truly ever safe no matter where they are.

So why the detail? Why does it really matter?

Horror films often take for granted the audience’s willingness to suspend belief when it comes to the movement of those being chased and their human pursuers (or material beings of some sort) through the spaces of the setting–ghosts can get a way with a lot that most other horror beings cannot. One of the classic tropes of horror films of late is the shutting of the bathroom mirror to find the bad thing or person standing behind them. Just on the surface of this trope, we have to assume that the floors that move down the hallway or bedroom to the bathroom don’t make a noise of any sort. We must also assume that the person will not sense someone coming into the bathroom before they close the medicine cabinet; all of which are not realistic assumptions to bolster the final payoff of the scare. They work purely as cheap jump scares, but they do not unnerve and stick with people.

By establishing the setting of the film in the first half with such detail, the audience can live with the characters in the film. We are able to hear the footsteps coming down the hall while Kristen cowers, crying, next to bed. The camera does not give the satisfaction of revealing their source until the final drop of suspense can be wrung from the audience. Where most horror films make their antagonists seen and heard, The Strangers seeks to unnerve by making its intruders either seen, not heard, or heard, but not seen. Or in the most tense moment of the film, the man in the mask is seen nor heard by the character even though the audience witnesses his presence in the background of the scene.

By establishing the setting of the film in the first half with such detail, the audience can live with the characters in the film. We are able to hear the footsteps coming down the hall while Kristen cowers, crying, next to bed. The camera does not give the satisfaction of revealing their source until the final drop of suspense can be wrung from the audience. Where most horror films make their antagonists seen and heard, The Strangers seeks to unnerve by making its intruders either seen, not heard, or heard, but not seen. Or in the most tense moment of the film, the man in the mask is seen nor heard by the character even though the audience witnesses his presence in the background of the scene.

This scene has Kristen going into the open plan kitchen. From the vantage point of the camera, the audience can see the main entrance, the dining table and the living room with a fire place. Kristen stands at the end of the jutting countertop, smoking a cigarette, and we see nothing but darkness giving way to the warm glow of the dining and living room from the fire. Slowly the audience sees something white slowly fade in from the darkness as Kristen moves parallel to the countertop to the sink to get a glass of water.

The figure is a man in a tweed-like suit with a sewn white fabric bag over his head with two eye holes carelessly cut out and a Sharpie line where his mouth should be. He is in the house coming from the main entrance observing her silently. She drinks the water, looks out the window. He continues to observe ominously from the main entrance. The camera switches to the intruder’s vantage point as she turns around, then the camera returns to the previous vantage point where the figure has moved back into the darkness. Slam. The door shuts abruptly and Kristen realizes that someone either came in the house or went out of the house.

It is at these moments in the film when Bertino plays with foreground/background aesthetics that thrust the audience into feeling a rather realistic sense of dread and terror. Since the house is a style that any of us could have grown up in or lived in–and probably a majority of Americans have at some point in their life, we are able to live very naturally within the world of the movie. The transgression of physical and psychological boundaries are felt in a rather visceral way because we can imagine ourselves in that house instead of Kristen and James. The details given to the setting create a way to deliver the audience into the beating heart of the narrative.

It m akes sense then that the final moments of the film take place in the daylight, in the most public space of the house (the living room). The house throughout the narrative of the film has been transformed from safe haven to a public spectacle to anyone who might have had the bad misfortune of happening upon the scene. The illusion of control and safety that we hold on to with clenched fists is shown exactly as it really is: a lie. The most violent moment in the whole film does not happen in the shroud of night, but in the dawn of morning where all could be seen. The doors to the house are open, windows broken, etc. and the spaces of the house and the outside meld together in a grand final statement for the film: the reality of this world and the evil that is in it subvert our constructed illusions and show us, in broad daylight, that terror can and will come from without and within. No one and no place is truly safe.

akes sense then that the final moments of the film take place in the daylight, in the most public space of the house (the living room). The house throughout the narrative of the film has been transformed from safe haven to a public spectacle to anyone who might have had the bad misfortune of happening upon the scene. The illusion of control and safety that we hold on to with clenched fists is shown exactly as it really is: a lie. The most violent moment in the whole film does not happen in the shroud of night, but in the dawn of morning where all could be seen. The doors to the house are open, windows broken, etc. and the spaces of the house and the outside meld together in a grand final statement for the film: the reality of this world and the evil that is in it subvert our constructed illusions and show us, in broad daylight, that terror can and will come from without and within. No one and no place is truly safe.