Oh! The Horror… | of Anthologies

There is something deeply satisfying about how peoples’ stories intersect and collide in the strangest ways. One of my good friends was recounting how he had gone to see the metal band, The Sword, in Fort Worth at Lola’s. As I was listening to him talk about it, there came a moment where a light bulb went off in my head:

“um, did it happen to be back in January of 2009?”

“yeah, that sounds about right actually.”

“yeah, I think we were at the same exact show and had no idea who the other was at the time.”

These kinds of things happen more often than we probably take into consideration. Even before it became cliché to say it’s a small world in the wake of globalizing technology, it was a small world. Take any four or five people on the street and stop to think, for a minute, about what a possible scenario would be where these four people were found in the same space, together, having not known one another before, and their lives being moved together in a way that defies rational explanations. The narrative formulated has the potential for a lot of unique creativity to thread their lives together into a singular, cohesive narrative. By doing this, we are taking a note out of the book of God. Chance and luck are not, traditionally, used to describe the will and sovereignty of God. This author affirms this belief. When people find these collisions with others in their lives, there is a reason. There is a story that is being threaded through all of humanity.

These kinds of things happen more often than we probably take into consideration. Even before it became cliché to say it’s a small world in the wake of globalizing technology, it was a small world. Take any four or five people on the street and stop to think, for a minute, about what a possible scenario would be where these four people were found in the same space, together, having not known one another before, and their lives being moved together in a way that defies rational explanations. The narrative formulated has the potential for a lot of unique creativity to thread their lives together into a singular, cohesive narrative. By doing this, we are taking a note out of the book of God. Chance and luck are not, traditionally, used to describe the will and sovereignty of God. This author affirms this belief. When people find these collisions with others in their lives, there is a reason. There is a story that is being threaded through all of humanity.

It is this, exactly, that makes anthology horror films—and other genre’s versions of them, to be fair—so fascinating. Perhaps the earliest anthology horror was 1919’s Eerie Tales and then the sub-genre blossomed in the 60s soon to, once again, disappear by the 90s with isolated films cropping up here and there. Most of them contain three to five short films, or vignettes, within the film’s runtime. However, what is perhaps the most intriguing aspect of all is the subsuming narrative around the vignettes, usually known as the wraparound story. This is the singular component that allows for the most creativity, yet also has the highest chance of failure. This is the element of anthology horror that aims to bring flesh to the imaginative game spoken of earlier. What thread will bind these vignettes together in a way that is satisfying as a film, the microcosm of the divine—or infernal, since we are talking horror—tapestry.

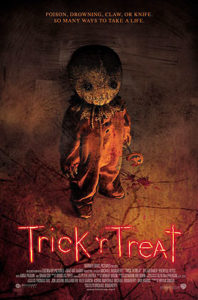

Many of these films took a more straightforward route by having a group of strangers gather together in a house and “tell” the tales that were being shown to us in each vignette. Often the climax of these wraparound stories were anti-climactic or ended in a less than terrifying game of “whodunit.” Some simply vied for a narrator who introduced each story without any  real attempt at connecting them together outside of their containment within the film. Then there are others that sought to tell a story that integrated the vignettes within its grand nightmare. One of the most notable of the recent examples of this was the terrific and streamlined Trick ‘r’ Treat (2007) where each story had the appearance of this strange little trick or treater with a burlap bag over his head who had a penchant for showing up whenever the blood and gore took place.

real attempt at connecting them together outside of their containment within the film. Then there are others that sought to tell a story that integrated the vignettes within its grand nightmare. One of the most notable of the recent examples of this was the terrific and streamlined Trick ‘r’ Treat (2007) where each story had the appearance of this strange little trick or treater with a burlap bag over his head who had a penchant for showing up whenever the blood and gore took place.

Trick ‘r’ Treat’s overarching story worked, in part, because all of the stories and the conception of how they were all tied together were done by one director who was also the writer. Whereas something like the V/H/S series of anthology horror had different directors and writers for each vignette and a different director, still, for the wraparound story. The first of the series is able to largely accomplish its aim with only a couple of vignettes that were misfires and a wraparound story that invites the audience into a wider world and conspiracy around secretive video tape collectors who seek out the tapes that contain the stories we see in each installment. It was perhaps one of the most ingenious ideas for an anthology wraparound. It’s too bad that not every vignette lived up to its promise in the first two films and the whole third act of the series was a mess in general.

Nonetheless, what these films are seeking to do is showing that luck may not be what it is cracked up to be and that there may be something more ordered within the genetics of mere coincidence than what we sometimes like to perceive. In a sense, we are practicing the art of seeking out another’s sovereign will. With horror, we might perceive this will as something damnable and evil. We might even give this being a name: Lucifer, Satan, the devil, etc. He is working all things toward his own will which is to attain our obedience and eventual destruction, hence all of the immortal slashers, the tentacle creatures coming from the void, the clown in the flood drain, etc.

However, if we are to believe what the Christian God spoke about Himself then we know that the powers and principalities that seek our destruction and obliteration will be fractured and brought to nothing. God, however, in his binding and life-giving tapestry is able to restore, heal and mend the frays and the severs in the thread that the evil one brought to fruition  through us and make the cloth even stronger because of them. The evil has been defeated already and now it is just digging its heals in and throwing a Hail Mary, knowing full well it will not succeed. God has won. His narrative around His creation and creatures will be finished. He will take all of the billions and billions of unique human threads full of story and character and weave them into a grand plot that incorporates the nightmares and the light.

through us and make the cloth even stronger because of them. The evil has been defeated already and now it is just digging its heals in and throwing a Hail Mary, knowing full well it will not succeed. God has won. His narrative around His creation and creatures will be finished. He will take all of the billions and billions of unique human threads full of story and character and weave them into a grand plot that incorporates the nightmares and the light.

Horror anthologies then could be seen as a smaller version of this concept. Various individual stories that are brought together underneath a bigger plotline that weaves them all together. The better the overarching wraparound is, the more convincing the nightmare becomes, and the closer to the truth we get about what is going on. The less we rely on coincidence and chance and seek out the ties that truly bind us all together—no matter how terrifying that narrative may be in the moment—the better off anthologies are and the better off we are as people. Where there is truth, there is light. Sometimes one must enter the darkest hours of the night to get there first. We can only hope that there are others on the same path who have been brought here by way of their own unique tale to find the light along with us.