of the 1980s

Oh, the 1980s. What a decade, what strange dichotomies befall us in digging into the film of this era. Read sites about film in the 1980s and you’ll see thinly disguised passive aggression towards the general cinematic output of the decade. It’s the age of “high-concept” filmmaking which is actually a truly ironic description considering the term meant films that could be marketed with a phrase or a short sentence—like Alien being “Jaws in space”—and often made for attraction to the lowest common denominator of audiences. Jaws became the first true “blockbuster” in 1975 and reinvigorated film promotion around the summertime which still holds true to this day. Lots of technology, action, and thrills were the trade of the decade and this model would hold beyond the 80s.

Oh, the 1980s. What a decade, what strange dichotomies befall us in digging into the film of this era. Read sites about film in the 1980s and you’ll see thinly disguised passive aggression towards the general cinematic output of the decade. It’s the age of “high-concept” filmmaking which is actually a truly ironic description considering the term meant films that could be marketed with a phrase or a short sentence—like Alien being “Jaws in space”—and often made for attraction to the lowest common denominator of audiences. Jaws became the first true “blockbuster” in 1975 and reinvigorated film promotion around the summertime which still holds true to this day. Lots of technology, action, and thrills were the trade of the decade and this model would hold beyond the 80s.

While, on the surface, the 80s may have seemed like a moment of status quo, perhaps the best way to understand the 80s is to look towards its music. When the term “one-hit wonder” is used, the first thought in most peoples’ minds is new wave, or “80s music.” Glossy sheens of synth machines and upbeat pop, often highly produced, got people on the floor at clubs dancing. It was the perfect follow-up to the disco of the 70s when it came to club music. However, 80s music was notorious for having quite serious and depressing lyricism that dealt with drugs, failed relationships, abuse by parents, cultural constraints, etc. If people were listening while dancing, they would feel the tension of these two internal worlds. This is the perfect reflection of the 80s. On the surface, everything seems commercial and glossy and economically healthy, but anyone who digs a little deeper into the decade will come to realize that the general conception of the 80s was all “high production.”

Ronald Reagan’s conservative understanding of how the government was supposed to take part in the lives of its citizens shifted the landscape in some long-term detrimental ways. His concepts of “trickle-down economics” and “war on drugs” ended up compounding the harshness of life for those in the lowest socioeconomic statuses and directed the beginnings of the high African American incarceration rates due to the suppressed opportunities of those in urban areas to be educated, taught skills, find jobs, get healthcare, and make it out of the projects. Often the easier—or only—option was to get into the game of selling drugs. Money could be made, but it made it easier for the government to put the sellers behind bars instead of the, often white, distributors who were providing the inventory. While the high production element of the conservative regime in the 80s led people to believe that America was healthy, the foundations of the country continued to crumble and suppress those people this nation has always tried to suppress. The depressing lyricism present underneath the glossy pop of American culture.

Ronald Reagan’s conservative understanding of how the government was supposed to take part in the lives of its citizens shifted the landscape in some long-term detrimental ways. His concepts of “trickle-down economics” and “war on drugs” ended up compounding the harshness of life for those in the lowest socioeconomic statuses and directed the beginnings of the high African American incarceration rates due to the suppressed opportunities of those in urban areas to be educated, taught skills, find jobs, get healthcare, and make it out of the projects. Often the easier—or only—option was to get into the game of selling drugs. Money could be made, but it made it easier for the government to put the sellers behind bars instead of the, often white, distributors who were providing the inventory. While the high production element of the conservative regime in the 80s led people to believe that America was healthy, the foundations of the country continued to crumble and suppress those people this nation has always tried to suppress. The depressing lyricism present underneath the glossy pop of American culture.

In this way, I think a case could be made that the film of the 80s—while geared towards wider audiences and general markets—is often struggling with this dichotomy. While seeing a film in a theater is a communal experience that is often hard to explain and can even make the worst film enjoyable, it wasn’t until the 80s that it became common place for the films on the big screen to be transferred to the small screen so that people could learn to actually live with the films. These days we take for granted the concept of “repeat viewings.” This wasn’t always the case. Before the 80s, people would see the film once—maybe twice—in a theater and whenever they wanted to revisit it, they would remember a slightly different film each time. Making some films color when they were black and white or remember events taking place that didn’t take place. Like the deterioration of actual film stock, the memory slowly loses the plot. With VHS coming into common use and the invention of the film rental market, films could be picked up and re-watched and the memory could be renewed. One picks up the finer details of a film that are easy to miss in the communal viewings at theaters. I think this technological shift from the creative deterioration of film narrative and details in the viewer’s memory over time to the increasingly granular focus on film details within a repetition of viewings may be the most important cinematic moment in the 20thcentury.

Another element of the 80s film industry that plays heavily into the discussion of 80s horror as well is the transition to a youth-focused industry. The fossilization of the “teenager” became a boon for the film industry to the point that the teen angst film, sex-comedy, and slasher films were largely geared towards them. John Hughes is considered to be one of the key figures of the 80s along with the “brat pack” of young actors that were featured often in his films. Youth culture in America was finally coming into its own and the “age of prosperity” made for a lot of young (white) people with expendable income and a lot of time on their hands to be the most consistent denizens of cinemas and rental profit.

Another element of the 80s film industry that plays heavily into the discussion of 80s horror as well is the transition to a youth-focused industry. The fossilization of the “teenager” became a boon for the film industry to the point that the teen angst film, sex-comedy, and slasher films were largely geared towards them. John Hughes is considered to be one of the key figures of the 80s along with the “brat pack” of young actors that were featured often in his films. Youth culture in America was finally coming into its own and the “age of prosperity” made for a lot of young (white) people with expendable income and a lot of time on their hands to be the most consistent denizens of cinemas and rental profit.

Horror in the 80s followed many of the industry compulsions, but where horror as a genre differed was in how horror as story-form works. Horror allows for the subconscious underbelly of a society to be incarnated. The anxieties, uncertainties, and general cultural hang-ups are often displayed within even the most cynical slasher sequel whether consciously or not, because horror as an art form requires an inquisition of those things which make us uncomfortable. There is plenty of good film criticism out right now that digs into some of the horror of the 80s that seemed mindless on the surface, but may have been getting in touch with the decay of society and culture and the repression of peoples during a time that was known as a boom for America. It should not surprise us that the current administration intentionally called back to Reagan’s campaign that also promised to “Make America Great Again” in a pre-internet era. If we look harder, the 80s may not be all it seems and this is what makes this decade of cinema so fascinating.

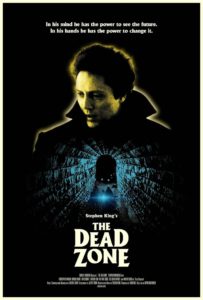

There is a deep cynicism present in horror of the 1980s. The anxieties of people during the decade were buried deep, but nothing stays buried forever. Cinema has the ability to cull out those things that we don’t want to investigate for fear that the knowledge may actually require us to act on its behalf. In my opinion, David Cronenberg may be the king of 80s horror. His films live in the flesh—both the literal and Biblical understandings—of humanity and his cynicism about society and humanity runs deep. Much of his filmography is celebrated and shows up in beautiful physical formats from Criterion Collection and Arrow Videos, but one of his lesser celebrated and analyzed films is a personal favorite: 1983’s adaptation of the Stephen King novel, The Dead Zone.

There is a deep cynicism present in horror of the 1980s. The anxieties of people during the decade were buried deep, but nothing stays buried forever. Cinema has the ability to cull out those things that we don’t want to investigate for fear that the knowledge may actually require us to act on its behalf. In my opinion, David Cronenberg may be the king of 80s horror. His films live in the flesh—both the literal and Biblical understandings—of humanity and his cynicism about society and humanity runs deep. Much of his filmography is celebrated and shows up in beautiful physical formats from Criterion Collection and Arrow Videos, but one of his lesser celebrated and analyzed films is a personal favorite: 1983’s adaptation of the Stephen King novel, The Dead Zone.

The film invites us into the life of Johnny Smith, a humble teacher, played by the always wonderful Christopher Walken, who is involved in an accident that puts him in a coma for five years. When he wakes up, he has entered a brave new world where his soon-to-be bride has moved on, his job is no longer, and he starts getting visions about the often brutal futures of people when he touches their flesh. He stumbles upon the political intrigue of a Leftist Senatorial candidate who, in Johnny’s vision, will end up as President ordering the deployment of weapons that will destroy all of mankind. Johnny sets out to change the future and save the world from inevitable apocalypse.

While, unlike many Cronenberg films, human flesh is not distorted, transformed, or alien, Johnny’s gift—or curse depending on the perspective—depends on the transaction of flesh with flesh. There is a psychic transference from person to person through intimate human touch. Johnny saves people by way of his visions, but what happens when the threat is larger than a kid drowning in icy water or sitting in a burning house? What about the dominoes that lead to the end of humanity? Does one end the life of one human in order to save all humanity? In that instance, is murder justified? These are just a few of the thought experiments that could be entertained in the wake of this film.

However, the most compelling aspect in the context of its release is how it views government officials. Greg Stillson seems to be a man of the people, fighting for the working class, and not caring about the blowback his ideas might have from the establishment. Yet Johnny, through his psychic visions, sees that it’s all just an act. Stillson is just as much a part of the establishment (i.e. the problem) as those on the Right. Their aim is the same: power. The end is the same: corruption.

However, the most compelling aspect in the context of its release is how it views government officials. Greg Stillson seems to be a man of the people, fighting for the working class, and not caring about the blowback his ideas might have from the establishment. Yet Johnny, through his psychic visions, sees that it’s all just an act. Stillson is just as much a part of the establishment (i.e. the problem) as those on the Right. Their aim is the same: power. The end is the same: corruption.

For a decade that still stands in the memories of many as a time of peace, economic growth, and strong governance, Cronenberg’s vision of government is deeply cynical about the nature of those we elect to govern us and about the narratives we give them the power to write. In the midst of perhaps the greatest political division we’ve seen in some time, both sides of the aisle look towards their own myopic narratives and make any other narrative “other.” Cronenberg’s vision of the 1980s is to trust no one, especially those in power. This cynicism runs deep in American history. The settlers looked at the British king and saw a vision (whether true or not) of religious and economic oppression, so they rebelled. They took the matter into their own hands and assumed that those in power would only descend into corruption. The South did the same when they saw the North try to take away their ability to buy and sell and own black bodies. They saw only the North’s descent into corruption—which is distinctly interesting considering Lincoln said he would have allowed slavery to exist if the Union were to be sustained. It’s cynicism all the way down. Understandably so at times.

However, cynicism can only lead to complacency/apathy or it can lead to the corruption of individuals. Johnny Smith falls into the latter as he attempts to assassinate Stillson to avoid the end of humanity. The problem, however, is that even with Stillson out of the way, who’s to say there wouldn’t be another person vying for power with the same outcome? Will our cynicism then guy us towards killing that person…and so forth down the line? Or not do anything and let the world end? How do we honestly recognize the corruptibility of those in power and still maintain that good can come out of it? Human endeavor may change things for a bit, but it’s treating the symptoms and not the disease.

However, cynicism can only lead to complacency/apathy or it can lead to the corruption of individuals. Johnny Smith falls into the latter as he attempts to assassinate Stillson to avoid the end of humanity. The problem, however, is that even with Stillson out of the way, who’s to say there wouldn’t be another person vying for power with the same outcome? Will our cynicism then guy us towards killing that person…and so forth down the line? Or not do anything and let the world end? How do we honestly recognize the corruptibility of those in power and still maintain that good can come out of it? Human endeavor may change things for a bit, but it’s treating the symptoms and not the disease.

This is where a Christian theological ethic is helpful. If we believe God is sovereign over his Creation and his creatures, then we have hope that even in the midst of corruption, God can and will bring good out of it. None of us are free from falling into corruption, it’s our fatal wound. Yet we can act knowing that the full weight of apocalyptic history does not land fully on us or

those we put in power, but in the hands of the one who knows us all intimately and uniquely and the one who lives in the ever-presence of the past, present and future. That should give us a freedom to act even when flaws and corruption are present in our actions or those in the systems we built.

Cronenberg’s The Dead Zone is a dreary vision fitting for his general take on existence and human flourishing. It’s a film that should receive more analysis and makes for a wonderful microcosm of 80s dystopian anxiety.