of the 1960s

As we continue into the 1960s, we see, once again, another dramatic shift in the film industry. Theater palaces are being forgotten in the wake of the creation of multiplexes. As history proves time and time again, capitalism stokes the fires of individual choice in the marketplace which, in turn, creates a paralysis within culture: if one screen with one movie is available, then the decision is made for those in that location. If there are multiple screens with multiple films—some lower-budget and some larger-budget—the democracy of choice has a tendency to favor the films with the biggest promotional budgets. The discrepancy between, in anachronistic terms, indie and mainstream film begins here and sticks around until industry shifts in the 80s start to balance the playing field once again.

As we continue into the 1960s, we see, once again, another dramatic shift in the film industry. Theater palaces are being forgotten in the wake of the creation of multiplexes. As history proves time and time again, capitalism stokes the fires of individual choice in the marketplace which, in turn, creates a paralysis within culture: if one screen with one movie is available, then the decision is made for those in that location. If there are multiple screens with multiple films—some lower-budget and some larger-budget—the democracy of choice has a tendency to favor the films with the biggest promotional budgets. The discrepancy between, in anachronistic terms, indie and mainstream film begins here and sticks around until industry shifts in the 80s start to balance the playing field once again.

The studios themselves are being bought out by wealthier investors and leadership is beginning to change over to a newer generation with different conceptions of how a studio needs to be run and films need to be made. The traditional studio mentality is largely null by the end of this decade. In the wake of the box office bust that was Cleopatra (1963), film epics begin to die out as well. The runtimes were overwrought, and profit depends on efficiency: how many tickets can we sell in a day? If a film is 3.5-4 hours long, the amount of showings drops and it becomes harder to make back the money spent on the film. The larger studios need to increase production, shorten runtimes and give viewers the ability to spend money on more than one film; hence the advantage of multiplexes.

The British, on the other hand, come into one of their most brutal and raw cinematic moments with their “kitchen sink”-style of filmmaking that focuses on the everyday life of blue collar workers, their paycheck-to-paycheck families, and the harsh, grimy realities of present-day British life. One of the subsets of this new wave is called “Angry Young Man” films, which concentrate on the tribulations of youth in the wake of seemingly failing democracy, poor working conditions, and family lives wasted by alcohol and drugs in an attempt to escape their impoverished conditions. Most such films find these young men in rebellion through sex, music, protest, and different kinds of drugs than their parents. The rawness of these films will find its way into the narratives and visuals of American cinema by the end of the decade; the Hays Code will relax in 1968 and filmmakers will be largely allowed to place content in their films that normally would have been struck down by the Code.

The British, on the other hand, come into one of their most brutal and raw cinematic moments with their “kitchen sink”-style of filmmaking that focuses on the everyday life of blue collar workers, their paycheck-to-paycheck families, and the harsh, grimy realities of present-day British life. One of the subsets of this new wave is called “Angry Young Man” films, which concentrate on the tribulations of youth in the wake of seemingly failing democracy, poor working conditions, and family lives wasted by alcohol and drugs in an attempt to escape their impoverished conditions. Most such films find these young men in rebellion through sex, music, protest, and different kinds of drugs than their parents. The rawness of these films will find its way into the narratives and visuals of American cinema by the end of the decade; the Hays Code will relax in 1968 and filmmakers will be largely allowed to place content in their films that normally would have been struck down by the Code.

Along with the British invasion are the arthouse and underground films, released under the radar in America and imported from foreign countries. Some of the finest film directors hit their stride in the 60s and will provide the internal code for cinema long after. Truffaut, Kurosawa, Fellini, Goddard, Bunuel, and Tati all make some of their most iconic films during the 60s. One could say that modern “prestige” cinema potentially has its origins in this decade with the influence from markets outside of the US. It also doesn’t hurt that the conflicts happening in America domestically (Civil Rights, assassinations, etc) and internationally (the beginning of the Vietnam War, Cuban conflict, etc) create an internal challenge to the nature of representation of peoples and history in Hollywood which foreign films only exacerbate by giving the US a picture of themselves and the world that doesn’t revolve around them.

In the midst of all of this, however, horror is becoming weird and darker in atmosphere and tone. Hammer horror films come into their own stream of sinister beauty by re-imagining classic horror fare within Gothic settings. Christopher Lee becomes another iconic vision of Dracula—debates comparing Lee and Lugosi will continue into the 21st century. Actors like Vincent Price and Peter Lorre find themselves in a string of Roger Corman produced/directed adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories which also embody the Gothic aesthetic. Underground horror is able to largely avoid censorship and opens up the boundaries of nudity, gore, and taboo subjects that would not have been allowed in the mainstream. While the 70s will showcase some of the most original horror films since the early days of horror, the 60s are able to create the blueprints with their grassroots subversion tactics.

In the midst of all of this, however, horror is becoming weird and darker in atmosphere and tone. Hammer horror films come into their own stream of sinister beauty by re-imagining classic horror fare within Gothic settings. Christopher Lee becomes another iconic vision of Dracula—debates comparing Lee and Lugosi will continue into the 21st century. Actors like Vincent Price and Peter Lorre find themselves in a string of Roger Corman produced/directed adaptations of Edgar Allan Poe stories which also embody the Gothic aesthetic. Underground horror is able to largely avoid censorship and opens up the boundaries of nudity, gore, and taboo subjects that would not have been allowed in the mainstream. While the 70s will showcase some of the most original horror films since the early days of horror, the 60s are able to create the blueprints with their grassroots subversion tactics.

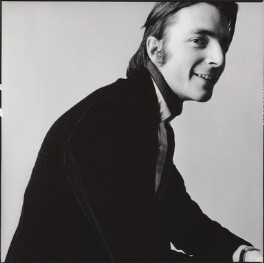

Witchfinder General, also known as The Conqueror Worm, rolls out to theaters in 1968 and will become director Michael Reeves’ last feature. He was only 24 years old when he co-wrote and directed the feature. He was under the mentorship of Don Siegel (Invasion of the Body Snatchers ’56) for a time and worked with the likes of Boris Karloff and Barbara Steele at the point where he began production on this film. It stars horror icon Vincent Price as the real-life Matthew Hopkins, a witch hunter during the English Civil War between 1644 and 1647. He hung more people in those three years than the 100 years prior combined. Price’s take on the role is deliciously cynical, bringing in the political and hypocritical subtext of Hopkins’ career. The film also stars Ian Ogilvy and Hilary Heath as the star-crossed lovers caught in the middle of Hopkins’ witch hunt. Ogilvy is no stranger to working with Reeves; he starred in some of his short and feature films. Witchfinder General will often be regarded as one of the best horror films produced in Britain.

If one really takes stock of the film as a whole, it wouldn’t be wrong to state that a good portion of it would fit within a melodrama taking place during wartime. The only part of the film that could be considered to be within the bounds of horror are the scenes showing the historical events that actually took place. Many innocent people were hung under the direction of Hopkins in real life and, while I will allow for the potential that they might have successfully hung a witch here and there(because I’m not against their existence), most of these people were probably hung at political behest or due to a complaint from a neighbor with pull. Price’s portrayal of Hopkins very clearly takes this reading to heart as we see his cavalier attitude towards the work he is doing, and how he is quick to find a way to name people “witch” when they are on to his games. Looking back on that time period of the English Civil War, one would have to do some impressive gymnastics to get away from that interpretation of Hopkins and his campaign during that small window of time.

If one really takes stock of the film as a whole, it wouldn’t be wrong to state that a good portion of it would fit within a melodrama taking place during wartime. The only part of the film that could be considered to be within the bounds of horror are the scenes showing the historical events that actually took place. Many innocent people were hung under the direction of Hopkins in real life and, while I will allow for the potential that they might have successfully hung a witch here and there(because I’m not against their existence), most of these people were probably hung at political behest or due to a complaint from a neighbor with pull. Price’s portrayal of Hopkins very clearly takes this reading to heart as we see his cavalier attitude towards the work he is doing, and how he is quick to find a way to name people “witch” when they are on to his games. Looking back on that time period of the English Civil War, one would have to do some impressive gymnastics to get away from that interpretation of Hopkins and his campaign during that small window of time.

What is so stunning about his film is how its depictions of hanging are so matter of fact and without pause or drama. The opening scene shows a poor woman being dragged by executioners to her hanging pole, with townsfolk following behind to behold the spectacle. A priest is walking alongside reading from a religious text. As they place the noose around her neck, the priest gives a nod, they knock the stool from under her, and she swings. No fanfare: we are left with piercing silence as she sways back and forth. The opening credits begin, and they are presented over saturated photos of women in pain, screams frozen on their faces. These are the numerous victims of the Witchfinder General.

This picture of the priest walking alongside, reading from a religious text and, not only sanctioning, but giving the final death nod, is a stirring indictment of a state that Christians and the Church, universal, have found themselves in throughout history. The closer to the bases of power the Church gets, the more ineffective it becomes in following the commands of Christ. The Church and Christian’s power is always in its weakness, when it is being truly persecuted to the point of death and martyrdom. Witchfinder General gives Christians an eye into how we are manipulated by those in power to do their will instead of the will of our Father. If the priest had been faithful he would have seen the tricks of the devil in all of this death. He would have seen that this was all just political expedience, in a world that uses the supernatural as excuse while not actually believing in it metaphysically. This is the problem with the State, or whatever the power base is: it uses the moral and metaphysical grounds of the faith in order to achieve its political goals, while rejecting the actual reality of the spiritual itself. This is no friend of the Church, and yet we fall for it almost every time.

This picture of the priest walking alongside, reading from a religious text and, not only sanctioning, but giving the final death nod, is a stirring indictment of a state that Christians and the Church, universal, have found themselves in throughout history. The closer to the bases of power the Church gets, the more ineffective it becomes in following the commands of Christ. The Church and Christian’s power is always in its weakness, when it is being truly persecuted to the point of death and martyrdom. Witchfinder General gives Christians an eye into how we are manipulated by those in power to do their will instead of the will of our Father. If the priest had been faithful he would have seen the tricks of the devil in all of this death. He would have seen that this was all just political expedience, in a world that uses the supernatural as excuse while not actually believing in it metaphysically. This is the problem with the State, or whatever the power base is: it uses the moral and metaphysical grounds of the faith in order to achieve its political goals, while rejecting the actual reality of the spiritual itself. This is no friend of the Church, and yet we fall for it almost every time.