Of The 1920s

The 1920s holds a special place within cinema history as German Expressionism makes its way onto American shores. Known for its angular, almost surreal, settings and its narrative gloom, German Expressionism gave silent cinema some of the most fantastical and figurative worlds and stories. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari strikes a unique pose in terms of horror cinema. It tells the story of a somnambulist–a sleepwalker–who is under the spell of Dr. Caligari and is told to go around the small town of Holstenwall, murdering innocent townsfolk. The striking appearance of the background expressionist art along with the ever so thin, languid face of Cesare, the sleepwalker played by Conrad Veidt, is enough to stick in the memory of anyone who sees the film.

The 1920s holds a special place within cinema history as German Expressionism makes its way onto American shores. Known for its angular, almost surreal, settings and its narrative gloom, German Expressionism gave silent cinema some of the most fantastical and figurative worlds and stories. The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari strikes a unique pose in terms of horror cinema. It tells the story of a somnambulist–a sleepwalker–who is under the spell of Dr. Caligari and is told to go around the small town of Holstenwall, murdering innocent townsfolk. The striking appearance of the background expressionist art along with the ever so thin, languid face of Cesare, the sleepwalker played by Conrad Veidt, is enough to stick in the memory of anyone who sees the film.

Beginning the discussion of the 1920s with German Expressionism may seem like a strange place to begin in such a busy and eventful decade for film history, however expressionism is significant to take into account as we see the transition from silent film to “talkies.” Dialogue and music began to vie for primacy with the moving image, the one element of cinema that separates it from other forms of artistic expression. As sound became incorporated in the late 1920s, the visuals of the film often took a backseat to the dialogue of the characters. It became easier for filmmakers to give in to the temptation of exposition-heavy scripts instead of visual description. Being told what is going on and what it all means is much less engaging and inclusive to the audience than being shown. The ambiguity of the image opens up channels of discussion and interpretation more than dialogue or narration can.

It makes sense then that German Expressionism led into the final gasp of silent film; at a height of potent visual language. As a critic, one might wonder whether the perfect “talkie” might be the one that comes the closest to having the visual audacity of silent films while still incorporating sound and dialogue. There is certainly a case to be made for that perspective.

Nonetheless, films were becoming epic “motion pictures” with romance, melodrama, horror, and swashbuckling adventure. Their runtimes were becoming longer especially with the films of D.W. Griffiths in the decade prior. Silent film was beginning to have a magical visual language all of its own and the communal experience of live organ or orchestration in the new “picture palaces” of the decade gave people an immersive experience that cinema still can provide to this day if we can pry our eyes from our phones long enough to get sucked in. However, technology and commerce, once started, have a hard time slowing down once they gain speed. The want of innovation, sound, and bigger and better film experiences shortened the life of a burgeoning silent film era where the visuals–out of necessity– were the central focus of the motion picture.

Nonetheless, films were becoming epic “motion pictures” with romance, melodrama, horror, and swashbuckling adventure. Their runtimes were becoming longer especially with the films of D.W. Griffiths in the decade prior. Silent film was beginning to have a magical visual language all of its own and the communal experience of live organ or orchestration in the new “picture palaces” of the decade gave people an immersive experience that cinema still can provide to this day if we can pry our eyes from our phones long enough to get sucked in. However, technology and commerce, once started, have a hard time slowing down once they gain speed. The want of innovation, sound, and bigger and better film experiences shortened the life of a burgeoning silent film era where the visuals–out of necessity– were the central focus of the motion picture.

Along with the increase in technological innovations, the 1920s saw the creation of motion picture studios, the largest being Paramount Pictures, followed my Universal, Fox 20th Century, and Warner Brothers. As the smaller studios faltered and were being bought up by these mammoths, profit, too, became a guide for what was becoming a successful industry in the global economy, not to mention the Capitalist markets of America. Between the technology and the drive for more profit, the silent film was due to go the way of the dinosaurs and, by the end of the 1920s, the writing was already on the wall.

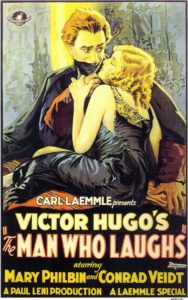

So, as we move into the world of dialogue and music, let us say goodbye to the silent era by looking at one of its last and best entries, Paul Leni’s 1928 film, The Man Who Laughs. Leni, a German director best known for The Cat and the Canary for Universal, had a significant film career in his home country before he came to America. Along with him, came his longtime working partner, Conrad Veidt, of Caligari fame. This film would be Leni’s second to last feature and last feature working with Veidt before Leni’s death a year later. The film is an adaptation of the Victor Hugo novel of the same name.

Technically The Man Who Laughs is more a romantic melodrama than it is strictly horror, however Leni relied heavily on the doom and gloom and sharp, angular visuals of German Expressionism in the film to created a dark, nightmarish 17th & 18th century England. On top of that, Veidt’s Gwynplaine–the title character–is terrifying to look at even when we, as the audience, are supposed to have empathy for the character. It was Veidt’s image as the laughing man that would be a central influence for the creation of Batman’s nemesis, The Joker. Ultimately, Jack Pierce, the makeup designer on The Man Who Laughs (and many of the Universal monster films later on), could be given the singular credit for one of the most enduring villains of all time.

Technically The Man Who Laughs is more a romantic melodrama than it is strictly horror, however Leni relied heavily on the doom and gloom and sharp, angular visuals of German Expressionism in the film to created a dark, nightmarish 17th & 18th century England. On top of that, Veidt’s Gwynplaine–the title character–is terrifying to look at even when we, as the audience, are supposed to have empathy for the character. It was Veidt’s image as the laughing man that would be a central influence for the creation of Batman’s nemesis, The Joker. Ultimately, Jack Pierce, the makeup designer on The Man Who Laughs (and many of the Universal monster films later on), could be given the singular credit for one of the most enduring villains of all time.

Conrad Veidt had to wear a mechanism that would draw the corners of his mouth back to a wide, unnatural smile with false dentures in his mouth to replicate the full disfigurement of Gwynplaine who had been cut intentionally by comprachicos–men who, in folklore, would mutilate children or stunt their growth in order to be jesters or mountebanks (con men). It is truly one of the most horrific character designs in cinematic history. Very hard to forget once it has been witnessed and it is only made more real by the expressive work of Veidt who largely had to act with movement and his eyes.

The film’s narrative follows after the defeat of Lord Clancharlie by James II when Clancharlie’s son is disfigured by comprachicos and left in England once the practice was outlawed. He happens upon a baby girl who is also abandoned named Dea. He carries her through harsh weather and finds shelter with the head of a traveling carnival show where Gwynplaine becomes a central proponent of his carnival draw. Dea, on the other hand, was born blind and she is in love with Gwynplaine, yet he constantly feels undeserving of her love because of his disfigurement. Once Queen Anne–who had come to power after James II–and the rest of the royalty in England find out of his inheritance to the wealth and status of his father, a grand plan is devised to allow the current heiress–Duchess Josiana–to remain in her status by marrying Gwynplaine. The ending strikes a similar feel to James Whale’s 1931 classic, Frankenstein, where we see Gwynplaine protesting the life that has been devised for him in order to go find Dea and live happily ever after.

While straightforward horror is sparse in the film, there are moments that play out like some of the best visual moments of the early cycle of Universal monster films. Small Gwynplaine trekking through an abandoned, desolate land with bodies swaying from poles all around him to the striking image of Veidt’s disfigured face and the hazy dreamlike quality of the main carnival production that featured “The Laughing Man.” All of it made for a romantic melodrama dressed in the mood and atmosphere of a horror film.

While straightforward horror is sparse in the film, there are moments that play out like some of the best visual moments of the early cycle of Universal monster films. Small Gwynplaine trekking through an abandoned, desolate land with bodies swaying from poles all around him to the striking image of Veidt’s disfigured face and the hazy dreamlike quality of the main carnival production that featured “The Laughing Man.” All of it made for a romantic melodrama dressed in the mood and atmosphere of a horror film.

Yet while we are taken aback by Gwynplaine’s face, we also feel a deep and abiding sympathy for him since this disfigurement was done unto him through no fault of his own. One of the clowns in the carnival show comes up to Gwynplaine after a performance, wiping his makeup off, and comments how lucky Gwynplaine is that he doesn’t have to wipe off his smile every night after a performance. The clown doesn’t realize how much Gwynplaine’s identity is marred by his face and how he can’t even accept the love of Dea because of it. Peoples’ uncaring and negative reactions to his face has disfigured his soul as well in such a way that he can no longer recognize unconditional love when it is offered to him. He wishes for nothing more than the ability to wipe away his disfigurement after the performance.

And, yet, Dea is constantly reminding him of her deep affection for him. He is the one that hides his face from her whenever her hands move down to where his disfigurement is. He’s afraid that once she “feels” the truth, her love will be rescinded. And at one point, he lets her touch his face and we, as the audience, fear in the moment, as her face turns from smile to puzzlement, that his worst fear is about to be made true. Yet her love remains intact. It was more discovery than it was horror. It was more sorrow over his pain than it was terror. And then utters these words–silently, then placed up on the screen:

“God closed my eyes so I could see the real Gwynplaine.”

The stumbling block for most was taken away for her to be able to love him as he needed to be loved. This sentiment could have been taken as an insensitivity in this day and age because we like to be accepted “as we are,” flaws and all. This is a great sentiment to be sure, but sometimes outward appearances or political affiliations or gender identification can cause pre-judgment. Gwynplaine was the way he was because of being seen as less than human before he had been known to anyone. However, it was the reverse with Dea. She knew him long before his deformity had been “revealed” to her. She knew his heart and that allowed for all of the rest to be loved equally each in its own time and way. God gave her the ability to see him for who he actually was instead of what he looked like. Grace upon grace.

The stumbling block for most was taken away for her to be able to love him as he needed to be loved. This sentiment could have been taken as an insensitivity in this day and age because we like to be accepted “as we are,” flaws and all. This is a great sentiment to be sure, but sometimes outward appearances or political affiliations or gender identification can cause pre-judgment. Gwynplaine was the way he was because of being seen as less than human before he had been known to anyone. However, it was the reverse with Dea. She knew him long before his deformity had been “revealed” to her. She knew his heart and that allowed for all of the rest to be loved equally each in its own time and way. God gave her the ability to see him for who he actually was instead of what he looked like. Grace upon grace.

It’s no different for the rest of us. The divine knows the very hairs on our head before we are a twinkle in our parents’ eyes. He knows us fully and intimately and loves us regardless of the things we end up doing, what we look like, who we become, etc. Waves of grace define a God with an unconditional love like that. He knows and because He knows, He loves. Not the other way around. That is love. That is what The Laughing Man receives from Dea and it restores his soul when the world seeks to to continue to destroy it.