Noah on the Modern Day Felt Board

If you heard the story of Noah and the great flood as a child, it’s likely you remember as I do sitting in a stuffy Sunday school classroom and watching as your teacher played it out on one of those wonderfully nostalgic felt boards. Or maybe you can recall the melody and some of the lyrics to the stuck in your brain for days song “Arky Arky” from having performed it in your children’s choir. Or perhaps you never grew up hearing the story.

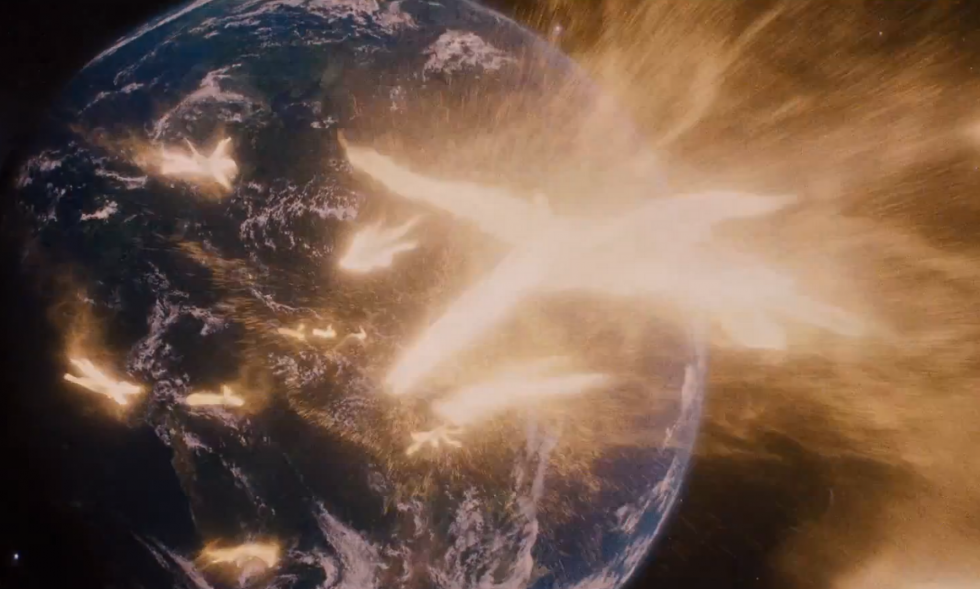

Whatever your background with Noah, it is likely you are familiar with the bare essential details: God told him to build and ark, the animals came two by two, Noah and his family were saved from the flood. It is a miraculous story of both God’s justice and His mercy. But did you ever put yourself in Noah’s place? Ever imagine yourself watching from the ark as the entirety of mankind begged and screamed for help as they drowned? It’s tough to think about. The true cost of bearing a burden that large is no children’s story. And the basic goal of Darren Aronofsky’s film Noah is to explore that burden and the man who bore it. The film, though, reaches for so much more.

Aronofsky and the Noah film have, as expected, come under fire. Aronofsky is a self proclaimed atheist (so it is claimed, I haven’t heard him personally say this) and we all saw a portion of the evangelical community come out condemning him and his work before it even opened in theaters. It’s a funny thing, condemnation. I am always baffled by those who believe as it says in Romans 8:1 that there is no condemnation for those who are in Christ, yet spend so much time condemning others. But it is par for the course in these days of social media.

The finger wagging is unfounded, however, and was mostly retracted after viewings of the film. The question remains- what are we afraid of with an honest telling of a biblical story such as this one? Clearly, nothing in life can be reduced to a felt board. There’s certainly nothing wrong with telling a children’s story, but we all grow up. And if we want to see what it is to be made in the image of our creator God, we cannot be afraid to face the reality of this world. Aronofsky does this with a grand sense of wonder in Noah, and we see from it both great beauty and great pain.

The most richly conceived aspects of the film are the many visual representations of nature. Aronofsky presents the creation of God with a strong reverence towards it, and he does it with his own ambitious creativity. Never have I seen a film take such an awe inspired view of God as creator as this one. All of Aronofsky’s films are visually powerful, stretching the limits of imagination. That approach on this film is crucial in helping us stretch the boundaries of our understanding of the biblical narrative, forcing us to ask questions we might not dare to on our own.

The film doesn’t seek to definitively give answers to the questions raised. Rather, it opens the possibilities of what isn’t said in scripture to simply say “God is capable.”

In the film we see Methuselah battle with a fiery sword that consumes masses of soldiers. It’s not in scripture, but does scripture allow for the possibility that God could have worked in this way? Absolutely. The film shows an entire forest sprout from a single seed passed down from the Garden of Eden. Again, not in scripture, but is this within the power of the Creator? Scripture says with Him all things are possible.

Perhaps the most controversial aspect of the film is the “Watchers” (who in media have often been crudely nicknamed “the rock people.”) Genesis 6:4 briefly mentions the Nephilim, another word for “giants,” and refers to them as “mighty men who were of old.” What could those men have looked like? What were their origins? We cannot know for sure, and there are many interpretations by scholars that vary greatly. Aronofsky takes the opportunity to stretch the imagination and presents them as very fantastical creatures, seemingly based loosely on an interpretation of the original Hebrew language, explaining them as fallen angels imprisoned in rock. This isn’t a random choice, either. Their presentation visually represents many of the themes that the film wrestles with- the cost of sin, the Justice of God, and as they help Noah in this version of the story they come to represent God’s provision in a radical way.

That is perhaps the most wondrous part of this film. I was deeply moved by how the continual artistic representations of God’s provision showed how limitless it can be. Aronofsky rightly juxtaposes this with the provision of man, showing the powerlessness and corruption of human hands. The fire-forged bronze weapons and cruel societal structures set up by the line of Cain are on display and we stare, along with Noah, into the evil that accompanies those creations.

Of course, then there is the presentation of Noah himself that was another point of controversy. We see a flawed individual coming to grips with trying to obey and complete a task of true eternal significance. Throughout the film, God is only referred to as the Creator, an accurate interpretation of how the people of this time would have perceived Him. It is often mentioned in the film, as we see in scripture, that man was made in His image. For Noah, this is a burden to bear and leads him to care for creation. For the central villain Tubal-Cain, this leads to pride and a disregard for creation. Aronofsky places a lot of significance on this aspect of belief. After all, this is a story of men reacting to belief- Noah to his belief in his Creator, and seemingly the rest of mankind to a belief in themselves.

There is a shot in the film just after Noah awakes from a vision of the coming flood. Noah leaves his tent in the early morning and we see him in almost two-dimensional shadow against the backdrop of a rising sun as he first begins to contemplate what he is being shown. His wife Naameh appears behind him as he tells her of what he has seen. We see this similar type of shot often through the film- with Adam, Eve and their children, and most often with Cain’s murder of Abel. Film is our modern day felt board, and this is an accentuated version of that. But much more, these cookie- cut shadows of the characters shroud their features, making them ambiguous. It allows us to follow the possibility that we could have been any of these people. Any of us could have been Noah and faced an impossible journey such as this. And would we have been able to obey after staring into the face of annihilation?

It is this type of visual achievement that makes the film engaging and relevant. But the film is not without some major issues, the fact of which has gotten a little lost in the controversy. The script starts to trip over its own feet 2/3 of the way through. Despite showing God’s provision and creation in a powerful way, a true display of redemption is lost in the end despite a good set up for it. The final moments almost make a recovery, but ultimately we are left with as many questions on filmmaking choices as we are about the struggle the film presents.

Yet just as the film asks me to place myself in the shoes of Noah, I cannot help but put myself in Aronofsky’s place. He didn’t strictly remake a biblical story. Instead, he gave us an important piece of art that imaginatively sets the world alive and dares to wade into the struggle of a man tasked with an almost unbearable journey. If I were at the helm of such a challenge, I would hope to make a piece of art as creatively bold as the nature of my creator. After all, we are made in His image. Flesh and blood, not felt.

*Special thanks to J.R. Forasteros for his article that taught me the definition of a “midrash.” And to Jason Windsor (@jasonwindsor) for reminding me of the song “Arky Arky” that I now cannot get out of my heady heady.