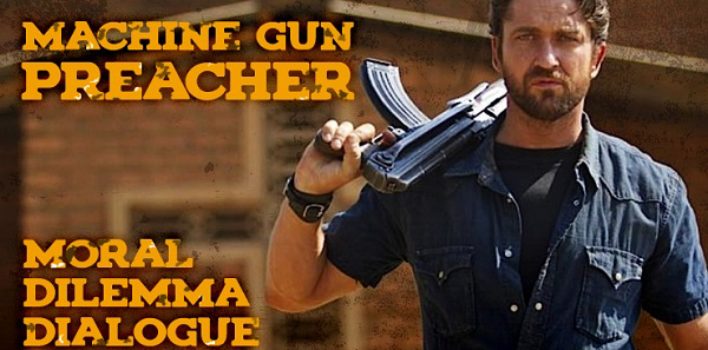

Moral Dilemma Dialogue: Machine Gun Preacher

In the Moral Dilemma Dialogue series, we take one film and examine a moral dilemma presented within it. Two people take opposing sides of the dilemma and argue their case. The arguments are presented sight-unseen of the opposing side’s approach, and with no rebuttal. That is where you, the audience, come in.

The Dilemma

Should Christians use violence to fight violence?

The Background

Sam Childers is a former drug-dealing biker who found God not long after his last release from prison. Upon seeing the living conditions of those in Sudan and Uganda, Sam feels compelled to do what he can to help. His first mission trip reveals the truth of the constant threat of violence and death surrounding these nations, particularly upon the children. Sam feels helpless to do anything, so he begins to fight fire with fight, literally.

Sam Childers is a former drug-dealing biker who found God not long after his last release from prison. Upon seeing the living conditions of those in Sudan and Uganda, Sam feels compelled to do what he can to help. His first mission trip reveals the truth of the constant threat of violence and death surrounding these nations, particularly upon the children. Sam feels helpless to do anything, so he begins to fight fire with fight, literally.

The approach of using violence to combat violence is one used often by military or police forces and other government authorities as a responsive means to some imminent or actual threat. It’s an approach that, while we may not like it, we could not find any philosophical inconsistencies with someone of a secular or naturalistic worldview. A Christian using it however, is another question. This is the dilemma we will be engaging as we examine the decisions of Sam Childers, professing Christians, and his choice to use violence to fight against violence brought upon innocent people. Mikey Fissel and Alexis Johnson will be delivering two sides of this debate, each from a Christian perspective. While they are both presenting their argument to the best of their abilities, they are doing so to get a conversation going. They each may actually hold different opinions in real life. We welcome your critique, questions, and of course your own perspective as well!

Perspective One: Mikey, Christian argument against using violence to fight violence

There is a picture of the Kingdom of Heaven that has intrinsically shifted my entire thinking about what the Gospel looks like in the world. It’s the picture the Bible paints of an upside down Kingdom— a Kingdom that doesn’t play by the rules that feel right, or easy. Think about what the Christian life is described as in the Bible: the first shall be last; the greatest will be the servants; to find life you must first lose it; the poor will inherit a kingdom; do good to your enemies; give away your possessions to more greatly receive; ultimate freedom through slavery.

Is this madness? Some would say so. Even though many people told Christ this, the LORD had already warned us, “For my thoughts are not your thoughts, neither are your ways my ways,” declares the LORD.” (Isa.55:8)

I point this out because I think it frames the larger idea we must consider before we react purely emotionally to a film like Machine Gun Preacher. I admit, it is very, very hard not to. In fact, I would say that if it does not stir some type of emotional reaction, you may need to do some self-evaluation. It is incredibly difficult to see the atrocities and evil (to the tune of 400,000 murders and over 40,000 child abductions) committed in Northern Uganda and Southern Sudan and not acquiesce when Sam Childers (the Machine Gun Preacher) asks us a simple, seemingly rhetorical, question:

I point this out because I think it frames the larger idea we must consider before we react purely emotionally to a film like Machine Gun Preacher. I admit, it is very, very hard not to. In fact, I would say that if it does not stir some type of emotional reaction, you may need to do some self-evaluation. It is incredibly difficult to see the atrocities and evil (to the tune of 400,000 murders and over 40,000 child abductions) committed in Northern Uganda and Southern Sudan and not acquiesce when Sam Childers (the Machine Gun Preacher) asks us a simple, seemingly rhetorical, question:

“If your child or family member was abducted today… if I said to you, ‘I can bring your child home.’ Does it matter to you how I bring them home?”

My initial reaction (especially after having seen this film) would be, “No, do whatever is necessary.”

But there is the rub. Are my ways and God’s ways aligning? Surely God desires my family and I to not be separated. Surely God desires justice. Surely God desires “good.” Surely.

As Christians, we would answer that God does desire justice— and He also desires “good.” So we must look to discover how God will bring about His justice. This is tricky because we must wade into the divide between our human response and God’s response.

Unfortunately, I have a limited word count, so we’re going to have to skip over a lot of the nuance…

Fortunately, there is a story that Sam Childers tells early on in the film that captures things beautifully. He tells a story of a young Sam who was caught up in quite a mess and had earned the very dangerous ire of other young men. These men pursued him and he feared for his safety. He recalls thrusting his hand into his pack to look for the shotgun that he kept there, instead, finding a Bible that his mother had put in its place. Young Sam assumed this was his end, sitting under a tree with his, “useless book.” The story took an inspiring turn when he describes the men passing him by as if they couldn’t even see him, implying that something was looking out for him that day. Sam even points out that things, “prolly woulda turned out pretty different if I had pulled out that shotgun instead of that Bible.”

What is Sam trying to convey with this anecdote? From my perspective, he is encouraging his congregation to remember that God is sovereign and that God has ways of resolving situations that are much different from our own. The cynic would say, “Ah, but this is just a safe anecdote on a Sunday morning, it is not meant to be applied to the harshness of real life, is it?” And I would answer, “Why not?”

What is Sam trying to convey with this anecdote? From my perspective, he is encouraging his congregation to remember that God is sovereign and that God has ways of resolving situations that are much different from our own. The cynic would say, “Ah, but this is just a safe anecdote on a Sunday morning, it is not meant to be applied to the harshness of real life, is it?” And I would answer, “Why not?”

One of my absolute favorite depictions of Christendom in media has to be Father Lanthom from the Netflix’s Daredevil series. When questioned by Matt Murdock about the use of violence (or murder) in stopping evil, Father Latham gives him a straightforward answer:

“There is a wide gulf between inaction and murder, Matthew. Another man’s evil does not make you good. Men have used the atrocities of their enemies to justify their own throughout history. So the question you have to ask yourself is, ‘Are you struggling with the fact that you have to kill this man but don’t want to, or that you don’t have to kill him but want to?’”

I believe the same question could be levied against our protagonist (and also us as justice-seeking viewers). And, to be fair to Sam (and us), we desire justice because we are created in the image of a God who is justice. But what does justice look like to God?

Marjorie Suchocki, in her book The Fall to Violence: Original Sin in Relational Theology, posits that only forgiveness will break the cycles of violence that enslave us. She outlines three ingredients for forgiveness–memory, empathy, and imagination. This, to me, is a brilliant observation and I can only hope to leave you with a few brief ideas that spawn from this.

Immediately, we must remember that violence is cyclical and is the opposite of what Christ tells us in Matthew (along with Paul in Romans) that we are to do when confronted with an enemy. Jesus, knowing the hearts of men, tells us to break the cycle of violence by loving our enemies and praying for those who persecute us.

It is incredibly difficult to have empathy for someone that we feel superior to. This is problematic when we’re reminded in scripture that, “No one is righteous— not even one.” (Rom. 3:10) If that’s true, then we must believe that we’re all on the same level and need help— not just the people we disagree with or see as evil. As Sam Childers says, “God don’t make trash, boy.”

This is where it takes some imagination and we harken back to Father Latham who reminds us that, “There is a wide gulf between inaction and murder.” All too often we are faced with a false dichotomy: Kill or be killed. And while I won’t get into the theological underpinnings of being free from the fear of death, we do have a wide gulf of options before violence is the answer including, various humanitarian and socio-economic solutions that would actually work towards forgiveness and peace.

I know putting violence on the back burner could be dangerous. I also know walking into a war zone with a first aid kit could seem foolish, but ,”The person without the Spirit does not accept the things that come from the Spirit of God but considers them foolishness, and cannot understand them because they are discerned only through the Spirit.” (1 Cor. 2:14) We have the Spirit to help us discern the LORD’s way— the ways that are upside down from our ways. And ultimately, as atrocious as the events depicted in Machine Gun Preacher are, if we believe that the root of those evils are part of a war that is being fought on a spiritual battlefield, then we need to be using weapons fit for that war (empathy, forgiveness, peace, grace) and not the ones made by men if we truly want to bring an end to it.

Perspective Two: Alexis, Christian argument in favor of using violence against violence

As children of God, living under the blood of Christ, violence should not be the place we turn to resolve conflicts. However, we live in a fallen world full of sin and despair, and there are instances where violence is the last resort and only way to abolish an evil.

One way sin creeps into our life is through omission. This means we fail to act when we know we should. Our apathy and complacency overcome our willingness to do what is right and just. Sin is a strong theme in Machine Gun Preacher, but especially as it pertains to sins of omission.

Sam Childers’ reason for choosing to act violently is because for so long the children in Sudan and into Uganda had been victims of the sin of omission. People failed to stand against Joseph Kony as he rose to power and enslaved children for his LRA – Lord’s Resistance Army. It isn’t that Sam Childers wasn’t the only one who knew or was willing to do anything, but I think in many ways he understood that this was an instance where violence was necessary to save countless children from death or becoming killing machines themselves.

Now, there is a point where Sam’s way crosses a line becomes an UNrighteous act, but we’ll get to that shortly. First, I want to dive into a Biblical stance on why violence is necessary in certain situations.

King David is not only one of the most well-known figures in all of human history, but he is also one of many signs of the coming of Christ. Though he is a sinner, like the rest of us, his story and his person are metaphors that point to Christ.

David was a shepherd in his youth, just like Jesus is shepherd of us all. One of the things David had to do as shepherd is rescue members of his flock from predators.

But David said to Saul, “Your servant has been keeping his father’s sheep. When a lion or a bear came and carried off a sheep from the flock, I went after it, struck it and rescued the sheep from its mouth. When it turned on me, I seized it by its hair, struck it and killed it. Your servant has killed both the lion and the bear; this uncircumcised Philistine will be like one of them, because he has defied the armies of the living God. The Lord who rescued me from the paw of the lion and the paw of the bear will rescue me from the hand of this Philistine.” – 1 Samuel 17: 34-37

The Philistine mentioned was Goliath, and this was David explaining to Saul that he believed God would give him victory over the giant. However, my point for bringing it up is what David said regarding what he did to rescue his sheep. It was violence, acts of violence against predators. He struck them, fought then, probably pried open their very jaws to free his lambs. In Job, a similar idea is echoed:

“I broke the fangs of the unrighteous and made him drop his prey from his teeth.” – Job 29:17

Putting this in a more personal perspective for people… If you are a parent, would you simply just allow an atrocity like rape, beatings, or death to happen to your child? What parent would not fight to their last breath and lay down their very lives before ever seeing such harm come to their child? It is a parent’s calling to protect their children and lay down their lives for them, and this calling is extended also to husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, extended family and friends. After all, “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.” – John 15:13

Putting this in a more personal perspective for people… If you are a parent, would you simply just allow an atrocity like rape, beatings, or death to happen to your child? What parent would not fight to their last breath and lay down their very lives before ever seeing such harm come to their child? It is a parent’s calling to protect their children and lay down their lives for them, and this calling is extended also to husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, extended family and friends. After all, “Greater love has no one than this, that someone lay down his life for his friends.” – John 15:13

This love and protection is first and foremost extended to us all through God’s love for us and through the sacrifice of his pure and spotless Son. Christ’s death on the cross was the greatest act of violence of all time, and yet it had to happen. The jaws and fangs of sin had to be broken to set the lambs free.

This question of violence in Christian faith has been dissected and debated for centuries. I am of the personal belief that no absolute position really can be taken. We are called to not live violent lives or to not “live by the sword,” however there are times throughout Biblical and global history where non-violence simply was not the available option to undo an evil. For example, were it not for violence and war, who knows how much longer the Holocaust during WWII would have lasted? Were it not for violence and war, who knows how much longer slavery might have prevailed in the United States?

St. Augustine proposed the Just War Theory that was later continued by St. Thomas Aquinas. Naturally, it’s a broader study than I have time to unpack here, but the condensed definition of the Just War Theory is this:

Just War theory postulates that war, while terrible, is not always the worst option. There may be responsibilities so important, atrocities that can be prevented or outcomes so undesirable they justify war.

In Childers’ case, he saw the repercussions of the violence in Sudan. He was a daily witness to the lambs in the mouths of lions. The fangs have to be broken when the predator is so unwilling to relinquish its prey. In one fierce sermon he gives to his congregation in the states, he declares that we are all sheep and that God doesn’t want sheep, he wants wolves with teeth to tear and the evil and injustice that’s out there in the world.

This is where a dangerous line can be crossed. When violence and war become a daily way of life, when do we, in turn, become predators ourselves? Sam Childers drifted into that way of being for a long time. At one point in the film, a relief worker points out that people are saying the same things about Sam that they said about Joseph Kony in the beginning of his rise to power when he was still considered a good leader. This is a very sobering moment; Sam is faced with the reality that he could drift into a very dark place, become his own enemy, if he doesn’t check himself or have a system of accountability for the actions he takes.

This is where a dangerous line can be crossed. When violence and war become a daily way of life, when do we, in turn, become predators ourselves? Sam Childers drifted into that way of being for a long time. At one point in the film, a relief worker points out that people are saying the same things about Sam that they said about Joseph Kony in the beginning of his rise to power when he was still considered a good leader. This is a very sobering moment; Sam is faced with the reality that he could drift into a very dark place, become his own enemy, if he doesn’t check himself or have a system of accountability for the actions he takes.

It isn’t until the end of the film when he has a compelling encounter with William, one of his rescued child soldiers, that Sam starts to see things differently. Though the movie doesn’t show us much beyond that point, we get the implication that he will no longer be the same after that.

Sam’s orphanage in Sudan still runs today where they regularly house more than 200 children and feed and shelter hundreds more. This place is vital to their community, and had to be paid for with a blood price. Local Sudanese who helped him over the years thought he was crazy to undertake such a mission with the LRA beating down on them, but he prevailed none the less by the grace of God. So with this in mind, we can only ask ourselves the same kind of questions I asked in regard to previous historical atrocities…

How many hundreds of children might not have been rescued from death or worse, were it not for Sam and his means of fighting for their freedom?

This is where the dialogue part comes in. Where do you fall on this dilemma? Does Mikey’s proposition that God’s ways are not our ways persuade you to take a more pacifist position in this instance? Or is Alexis correct, this is one of those times when a just war can be waged to put a stop to true evil? Please vote in the poll, and let your voice be heard by commenting below!