It’s The Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown – 50 Years of Misplaced Sincerity

Halloween time is fun but is mostly lost on me today. I enjoyed dressing up in costumes as a kid, but in the ensuing years, it seems that the most charming aspects of Halloween are being supplanted by the need to shock and disgust. The proliferation of scare mazes is a testament to this notion.

However, I take great delight in knowing that there are some pieces of Halloween entertainment that transcend such fads. For five decades, It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown has delighted television audiences with wit, heart, honesty and a touch of melancholy – things that flowed effortlessly from the pen of Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz.

However, I take great delight in knowing that there are some pieces of Halloween entertainment that transcend such fads. For five decades, It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown has delighted television audiences with wit, heart, honesty and a touch of melancholy – things that flowed effortlessly from the pen of Peanuts creator Charles M. Schulz.

After the critical and public triumph of A Charlie Brown Christmas (which was produced with very little budget and time) the previous December, and the similar success of Charlie Brown’s All-Stars in early 1966, CBS came to producer Lee Mendelson and said they wanted another Peanuts special – and it had to be a hit like the last two. If it wasn’t, CBS would probably stop ordering Peanuts animated specials.

Luckily, Mendelson, Schulz and animation director Bill Melendez were up to the task. The creative trifecta took Schulz’s concept of Linus believing in the Great Pumpkin (originally introduced in the comic strip in 1959) and turned it into an animated narrative.

Suffice to say that when It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown first aired on October 27, 1966, it was a tremendous hit. After that, CBS no longer threatened to pull the Peanuts plug. The show has been airing on network TV each year ever since.

The art is outstanding. The bigger budget can definitely be felt. The night sky has hints of gray, blue and purple, giving the setting a magical, twilight feel. And the characters are beautifully rendered – their simple animation being part of the charm of the show. Also, introduced in this show for the first time in animation were two tropes of Peanuts that would extend into the decades: Charlie Brown’s attempt to kick Lucy’s football and Snoopy’s imaginative trips to shoot down the Red Baron as the World War I Flying Ace.

The art is outstanding. The bigger budget can definitely be felt. The night sky has hints of gray, blue and purple, giving the setting a magical, twilight feel. And the characters are beautifully rendered – their simple animation being part of the charm of the show. Also, introduced in this show for the first time in animation were two tropes of Peanuts that would extend into the decades: Charlie Brown’s attempt to kick Lucy’s football and Snoopy’s imaginative trips to shoot down the Red Baron as the World War I Flying Ace.

The aforementioned Flying Ace sequence is one of the greatest pieces of storytelling animation, period. Bill Melendez takes the audience on a journey into Snoopy’s head – using sound effects and limited action.

I covered its brilliance in depth last year when I reviewed The Peanuts Movie – as I felt those filmmakers didn’t really understand the concept based on their peculiar execution of it in their film.

My other favorite piece of animation in the show again stars Snoopy, and the piano virtuoso, Schroeder. Snoopy’s disposition changes hilariously as Schroeder bounces from a bouncy march to a melancholic melody and back.

What makes this sequence special is not just the astonishing conveyance of emotion (without words, no less), but the little history lesson behind the tunes Schroeder plays. All of them are real songs from the WWI era. It was as if Schulz was teaching me things without even trying (and better than most of my schoolteachers).

Along with improved animation and design, the music to Great Pumpkin was a definite leap forward. Once again composed and performed by Vince Guaraldi and his cadre of geniuses, the music’s signature jazz feel is blended with other styles, like a waltz. Guaraldi also gives the jazz a spooky tone, especially in the title sequence. I think this is my favorite music in any of the Peanuts specials.

The music and animation are examples of the simple sophistication of the Peanuts characters. This pseudo-intellectual popular entertainment has fascinated me since I was a child. Reading the comic strip with my grandmother and viewing the many TV specials and films, I learned a lot from Charles Schulz. Aside from large vocabulary words and interesting historic concepts, I learned about the realities of life, and how to deal with its problems.

Seeing children not that much older than myself at the time having existential discussions with themselves and each other was interesting. It invited me to ponder these heavy concepts myself. In fact, A Charlie Brown Christmas was one of my earliest introductions to the true meaning of the titular holiday and is no doubt responsible for planting a seed in my soul, pointing me toward the Lord later in life.

“There are three things I have learned to never discuss with people: religion, politics and the Great Pumpkin.” Linus

It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown is just as spiritually deep as A Charlie Brown Christmas – perhaps more so. It isn’t explicitly about Christianity, as the Christmas special was, however. Great Pumpkin is a much more broad discussion focusing on faith itself.

Though his personal faith was complex, I think what Charles Schulz was expressing in It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown, among many things, was an examination of blind faith. Linus has an unwavering belief in the Great Pumpkin – a Santa Claus-like figure who gives presents to good children on Halloween night – even though the magical gift-giving gourd eventually lets him down.

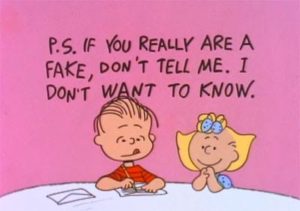

A closer examination reveals that Linus has no real reason why he believes, at least ones that are not present in the narrative. And when writing a letter to the Great Pumpkin, Linus asks to kept in the dark if it turns out the Great Pumpkin is indeed not real. The irony of this situation is glaring, as Linus, throughout both the strip and the animated specials, is the primary source of the franchise’s signature philosophical, historical and spiritual postulating.

Atheists and agnostics point to Linus’ blind faith as an indictment of belief, specifically Christian belief. But there is a misconception here because at no point in the Bible does God ask us to follow Him blindly.

“‘Come now, let us reason together,’ says the Lord…” Isaiah 1:18

Linus’ faith in the Great Pumpkin is not based on anything but the story he’s concocted in his own mind, as well as his own “sincerity.” The evidence for Christ’s existence is much more compelling and comes from multiple sources over hundreds of years, including secular ones. In fact, there are many non-Christian accounts of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth.

Linus’ faith in the Great Pumpkin is not based on anything but the story he’s concocted in his own mind, as well as his own “sincerity.” The evidence for Christ’s existence is much more compelling and comes from multiple sources over hundreds of years, including secular ones. In fact, there are many non-Christian accounts of the existence of Jesus of Nazareth.

But philosophically speaking, it is incredibly juvenile to compare God to the Great Pumpkin. The Great Pumpkin is a gift-giving entity that fulfills material wants and desires, and nothing more. Sincerity in one’s belief will be rewarded by earthly items – things that, as Jesus said, “moths and vermin will destroy, and where thieves break in and steal.” (Matthew 6:19)

God fulfills spiritual needs – the eternal desires that every person was created to experience. And there is only one real gift God gives us: the gift of salvation through Jesus Christ. God’s promise is objective and the same for everyone. The subjective assumptions of Linus’ beliefs are not as certain.

The sincerity of one’s beliefs means absolutely nothing in a world of objective truth. I could believe with all the sincerity in my soul that the sky is purple, and I could spend my time trying to convince everyone I know that the sky is purple. But my honest sincerity doesn’t make the sky any less blue that it objectively is.

There is an objective right and a wrong when it comes to belief. Linus’ faith is blind because he doesn’t desire evidence or ask questions about his line of thinking. God invites us to examine His story constantly – just like Jesus Himself invited Thomas to examine His hands and feet for the scars of crucifixion.

It’s the Great Pumpkin, Charlie Brown is not just an outstanding Halloween entertainment tradition. It is an interesting examination of belief and what blind faith leads to. It is true that we can’t be 100% sure of anything. But just because we are 99% sure, doesn’t mean we need to throw everything away. That’s what faith actually is. It’s trust – trust in God that is backed by evidence. And it is not the sincerity or power of your belief that saves you, it was His actions on the cross that did.