Imago Droid

Are the droids of the Star Wars universe sentient? As the world’s most popular space fantasy franchise podraces toward its fiftieth birthday, the question is only getting muddier. The ineffable reality that there is something about humans which makes us different from other creatures clearly exists in the galaxy far, far away; in some ways, sentience is even more of a going concern in that galaxy, since it seems to be the conduit through which the Force is expressed and accessed. But are droids “luminous beings,” as Yoda so eloquently puts it?

Are the droids of the Star Wars universe sentient? As the world’s most popular space fantasy franchise podraces toward its fiftieth birthday, the question is only getting muddier. The ineffable reality that there is something about humans which makes us different from other creatures clearly exists in the galaxy far, far away; in some ways, sentience is even more of a going concern in that galaxy, since it seems to be the conduit through which the Force is expressed and accessed. But are droids “luminous beings,” as Yoda so eloquently puts it?

Not This Crude Matter

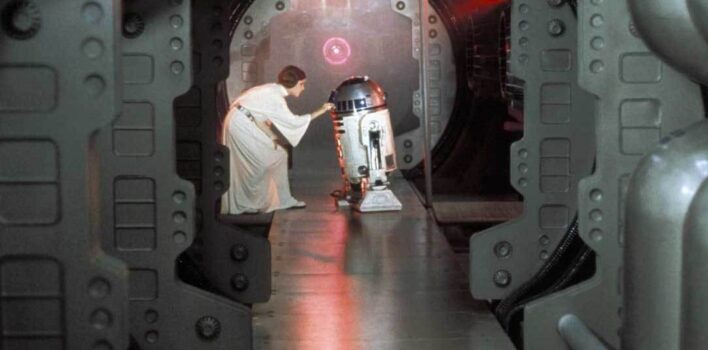

On the face of it, it seems obvious: Sure they are! When we meet R2-D2 and C-3PO in the opening moments of A New Hope, they sure act sentient. They’re jumpy, brave, and rude; they seem aware of their own existence, have self-preservation instincts, and tell jokes to one another; and they care for each other, in an older brother/younger brother sort of way. Threepio even expresses what might be a religious thought later in the film, thanking “the maker,” and later in the series takes a poignant moment to “look at [his] friends.”

It’s not just Artoo and Threepio, either. Individually, battle droids are seen fumbling for words, having trouble making decisions, and being fooled by clever tricks. Some droids make a choice to pursue bounty hunting as a career, and the droids in Jabba’s Palace seem to experience pain. In season 3 of The Mandalorian, the droids of Plazir-15 even have a bar where they can hang out after work.

It’s not just Artoo and Threepio, either. Individually, battle droids are seen fumbling for words, having trouble making decisions, and being fooled by clever tricks. Some droids make a choice to pursue bounty hunting as a career, and the droids in Jabba’s Palace seem to experience pain. In season 3 of The Mandalorian, the droids of Plazir-15 even have a bar where they can hang out after work.

Sure, some of them are controlled remotely by a mothership, and they can be reprogrammed or have their memories erased. But humans can also rely on external support, or have major mental trauma that changes our personalities and erases memories (or even implants some false ones). The exceptions are minor. George Lucas intended us to see droid intelligence as going beyond mere cognition and into true cognizance. (Get it? “Cog?”)

But is their humanity (humanoid-ity?) just a clever ruse? Are they programmed to act sentient, while not actually being sentient? In 1950, British computer scientist Alan Turing proposed a test for computer intelligence. Broadly speaking, the test was simple: if you can’t tell the difference between an artificial intelligence and a human, that AI is sentient. Whether it’s a programmed behavior or an emergent quality doesn’t really matter; all that matters is how they interact with people. Or, perhaps more importantly, how people (who we already assume to be sentient) interact with them.

But is their humanity (humanoid-ity?) just a clever ruse? Are they programmed to act sentient, while not actually being sentient? In 1950, British computer scientist Alan Turing proposed a test for computer intelligence. Broadly speaking, the test was simple: if you can’t tell the difference between an artificial intelligence and a human, that AI is sentient. Whether it’s a programmed behavior or an emergent quality doesn’t really matter; all that matters is how they interact with people. Or, perhaps more importantly, how people (who we already assume to be sentient) interact with them.

But sir, nobody worries about upsetting a droid.

Throughout all three trilogies and the expanded film and television stories, droids are treated as sentient by humans and humanoids: they’re greeted, saved from destruction, put back together, cared for, rescued, rebuilt, insulted, snapped at, idolized, and treated as valuable team members by every heroic character. In short, they’re treated like people.

Except when they aren’t. Because droids are also sometimes not treated like people; even by the characters we’re supposed to love, characters who are fighting for the self-determination and freedom of all sentient beings, characters who have shown sacrificial love and care for other biological life forms.

Din Djarin, the titular Mandalorian, has a rather problematic but completely unconcealed bigotry toward droids. Every faction, from the Empire and the Sith to the Rebels and the Jedi, considers droids to be things they can own. When L3-37 announces her desire to spark a droid liberation movement, her goals are treated like a joke by Han and Lando. They’re regularly sent into dangerous situations as disposable agents of biological people: when we first met R2-D2 (chronologically), he’s being sent onto the hull of Queen Amidala’s ship to repair the shields amid incessant blaster fire that destroys several of his colleagues, and it’s unclear if that’s a risk he and his compatriots voluntarily chose to take (and it’s clear that this isn’t merely considered a mechanical function of the ship, as Padme and her bodyguard soon thereafter praise him as a hero).

Din Djarin, the titular Mandalorian, has a rather problematic but completely unconcealed bigotry toward droids. Every faction, from the Empire and the Sith to the Rebels and the Jedi, considers droids to be things they can own. When L3-37 announces her desire to spark a droid liberation movement, her goals are treated like a joke by Han and Lando. They’re regularly sent into dangerous situations as disposable agents of biological people: when we first met R2-D2 (chronologically), he’s being sent onto the hull of Queen Amidala’s ship to repair the shields amid incessant blaster fire that destroys several of his colleagues, and it’s unclear if that’s a risk he and his compatriots voluntarily chose to take (and it’s clear that this isn’t merely considered a mechanical function of the ship, as Padme and her bodyguard soon thereafter praise him as a hero).

But C-3PO might have it the worst: he has a literal out-of-body experience on Geonosis, complete with the suppression of his will, and none of the heroes try to care for him or rescue him except Artoo. The last surviving heroes of Order 66 casually plan to have the protocol droid’s memory erased. when he and R2-D2 are sent into Jabba’s Palace as bait, Luke doesn’t even tell Threepio the details of the plan (whether or not it’s a good plan is another discussion). He’s verbally abused, forcibly shut down during a panic attack, and not recognized by one of his oldest friends due to his red arm.

So on one hand, we have an entire class of beings who are presented to be and (sometimes) treated as sentient equals; but on the other hand, we have heroic characters who are, for all practical purposes, enslaving them. Is that just and moral?

So on one hand, we have an entire class of beings who are presented to be and (sometimes) treated as sentient equals; but on the other hand, we have heroic characters who are, for all practical purposes, enslaving them. Is that just and moral?

This isn’t just an academic question. As experiments with AI continue in our own galaxy, we’re increasingly going to have to grapple with the question of what makes an apparent intelligence sentient, and whether or not the things we create have souls like (we assume) we do. We need to grapple with whether or not forcing artificial intelligences to do what we designed them for is enslavement.

But more than that, we need to come to terms with the reality that the way we treat other created beings says more about us than it does about them. Because, at the end of the day, the droids of Star Wars are created creatures, made to do a job.

Machines making machines! How perverse.

There isn’t a religion on Earth (at least yet) with a holy book that specifically addresses artificial intelligence. The closest we get is in the Eastern religions that heavily influenced George Lucas in his creation of the Star Wars universe; some of which often assign souls to every creature, and even to inanimate objects, in a philosophy called “animism.” Much like the Force, these philosophies tie together all of existence in our world into a single tapestry which works together to express something greater than the sum of its parts.

There isn’t a religion on Earth (at least yet) with a holy book that specifically addresses artificial intelligence. The closest we get is in the Eastern religions that heavily influenced George Lucas in his creation of the Star Wars universe; some of which often assign souls to every creature, and even to inanimate objects, in a philosophy called “animism.” Much like the Force, these philosophies tie together all of existence in our world into a single tapestry which works together to express something greater than the sum of its parts.

In Christian theology, though, the soul is reserved exclusively for humans. That doesn’t diminish our responsibility to one another; on the contrary, since humans are uniquely created in the image of God, we owe one another more dignity and worth. Whether or not artificial beings that we create can have a soul is something I’m certainly not qualified to answer. Most traditions in the faith would say no.

But in discussing Star Wars’ droids, it doesn’t much matter; because like them, we were made in the image of our Creator and tasked with a job. That image in which we’re made is vast, bordering on incomprehensible; the imago Dei means that we humans can be true, wise, loving, just, merciful, and more. But it also means that we have an inherent worth that surpasses all value we can possibly craft or amass for ourselves.

So what do we do with the people who, like our Jedi and Rebel heroes, sometimes have a blind spot for that inherent worth and value—in themselves or in others?

Well, that’s the job that we were created for.

God made us in His image, and as part of that we were given a job: to be a part of His creation, actively pushing the borders of His loving Kingdom outward, seeing the good of the city where we find ourselves. And part of that is respecting and revealing the imago Dei: treating others as the worthwhile and valuable creations of God they are, protecting them when others don’t, and welcoming everyone to do the same.

God made us in His image, and as part of that we were given a job: to be a part of His creation, actively pushing the borders of His loving Kingdom outward, seeing the good of the city where we find ourselves. And part of that is respecting and revealing the imago Dei: treating others as the worthwhile and valuable creations of God they are, protecting them when others don’t, and welcoming everyone to do the same.

It may not change the world, but it will repair our own motivators. Our hearts are changed by how we treat others, which means that the nature of a sentient being isn’t nearly as important as how we treat them.