Director’s Cut| Wes Anderson’s ‘Rushmore’

“The secret, I don’t know. I guess you’ve just gotta find something you love to do and then do it for the rest of your life. For me, it’s going to Rushmore.” -Max Fischer

“The secret, I don’t know. I guess you’ve just gotta find something you love to do and then do it for the rest of your life. For me, it’s going to Rushmore.” -Max Fischer

In an interview, Schwartzman talks about asking his mom, Talia Shire (formerly Talia Coppola, best known for playing Connie Corleone in The Godfather), how he should handle the interview. Talk about learning from the best. The way the Special Features section tells it, Jason Schwartzman (at the time, still the drummer for California-based band Phantom Planet and zero acting credits to his name) came into the casting interview wearing a blazer with a handmade Rushmore patch sewn on. With film heritage running through his family, it seems he was destined for greatness. Rushmore would go on to jumpstart Schartzman’s career while also taking Bill Murray’s in a new, slightly more cult and indie film oriented direction.

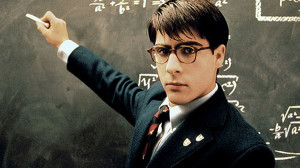

Wes Anderson refers to Rushmore as somewhat autobiographical with the school itself being very similar to his own primary school experience. The film tells the story of Max Fischer (Schwartzman), a young renaissance man at a private school in Houston. In early scenes it is made clear that Max is involved in nearly every extracurricular activity— except studying. He’s a playwright, a fencer (is that what they’re called), a multi-linguist (at least in his mind), and not the least of which, a self-assured Casanova.

Most of the story centers around his attraction and love for the school’s young teacher, Rosemary Cross (Olivia Williams), and his delirious belief that it may just work out between him, a 15-year old, and her, a young widower. She reminds him of this distinction early on. As they sit at a table in the library, Max pours her a glass of lemonade, replaces her pen, and returns to his seat.

Rosemary: “Max, can I ask you something?”

Max: “Sure.”

Rosemary: “Has it ever crossed your mind that you’re far too young for me?”

Max: “It crossed my mind that you might consider that a possibility, yea.”

Rosemary: “Quite apart from the fact that you’re a student, and…”

Max: I’m not trying to pressure you into anything Ms. Cross. I’m surprised you brought it up so bluntly.”

Max is ever in control. A director and writer, he casts the play and controls the movements. Everyone in the story that surrounds him finds themselves bent to his will (again, in his mind). These moments of control never fail to backfire, recoiling away from him at an alarming rate. The friends he has often sense this about him. They recognize his ability to manipulate his way into and around any situation he wishes, but they also recognize that his manipulations do often backfire. Coincidentally, in spite of his attempts at control, Max often finds himself just as lonely as his adult counterpart, Herman Blume (Murray).

Max is ever in control. A director and writer, he casts the play and controls the movements. Everyone in the story that surrounds him finds themselves bent to his will (again, in his mind). These moments of control never fail to backfire, recoiling away from him at an alarming rate. The friends he has often sense this about him. They recognize his ability to manipulate his way into and around any situation he wishes, but they also recognize that his manipulations do often backfire. Coincidentally, in spite of his attempts at control, Max often finds himself just as lonely as his adult counterpart, Herman Blume (Murray).

Herman Blume is actually successful in many ways, but relationships aren’t one of them. The very first time we meet his family, they are enjoying a late summer pool party, and he is watching as his wife sits and flirts with another man. Instead of engaging, he recoils, climbing to the top of the diving board, a cigarette perched on his lower lip, and cannonballs off. His need for affection and attention is so great that he fails to see his family’s obvious attempts to grab his. He isn’t able to recognize that his wife’s flirting is being done in hopes that he will engage her, and that his kid’s terrible attitudes are being done in hopes that he would engage them.

The way in which these two individuals contrast each other is, well, something Wes Anderson does so well in Rushmore. Max is truly loved by his friends (when he isn’t trying to control them). His father is a kind man, insistent in his love for Max. Like a good father, he is patient for his child’s realizations, knowing that they will likely come at the very end of the movie, or at least somewhere near the climax. Meanwhile, Blume, struggling under the weight of what he sees as a failing marriage and two nauseous children, seeks out Rosemary, at first to help Max and then for himself. Ultimately, he falls into the same trap he’s angry with his wife over. He falls for her, wanting to find hope in some new lover, only to have that relationship fail too.

Max and Herman live distinctly different lives, but both act like children in the face of their own mortality and loss. As with most films, it is not until the conclusion that these two recognize their mistakes. Through those mistakes, they find hope in new opportunities for love and renewed relationships. For Herman Blume, he finds hope and a sort of redemption in the form of a new relationship, founded on his own sincerity with Rosemary, while Max’s hope is found in his play— the story of man’s depravity while also portraying a sincere picture of love in the midst of a great war. Max has changed. The girl Max never noticed, he now seeks to have on his arm. The father Max oft ignores and lies about, he now shows pride in.

Max and Herman live distinctly different lives, but both act like children in the face of their own mortality and loss. As with most films, it is not until the conclusion that these two recognize their mistakes. Through those mistakes, they find hope in new opportunities for love and renewed relationships. For Herman Blume, he finds hope and a sort of redemption in the form of a new relationship, founded on his own sincerity with Rosemary, while Max’s hope is found in his play— the story of man’s depravity while also portraying a sincere picture of love in the midst of a great war. Max has changed. The girl Max never noticed, he now seeks to have on his arm. The father Max oft ignores and lies about, he now shows pride in.

Rushmore does not tell a particularly innovative story, but it does tell that story in a particularly human way. It’s not likely that we would ever witness an adult male actively plot to wreck the life of a 15-year old, but Anderson’s storytelling makes the two’s rivalry believable (while Bill Murray uses this opportunity to re-launch his career as the godfather of the film industry). For Max, even though Rushmore’s not where his story ends, it’s because of the things he goes through there that he eventually experiences a journey towards hope.