The Commodification of Gomer in Hosea (2019)

“I can’t go up there. But you can love me down here.”

—Cate

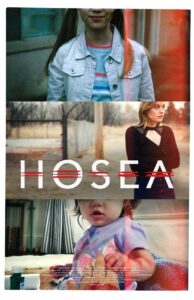

Hosea, a new film by filmmaker Ryan Daniel Dobson, is a creative and gritty take on the book of Hosea that manages to capture the honest and unfiltered nature of the text. The R rating is due to a few F-bombs and strong sexual themes. What stands out the most for me though is the filmmaker’s willingness to sit with the hard language of the text and to wrestle with it in terms of the challenges it presents for reading it as Christians today.

In terms of being a kind of interpretive process, the film has the feel of a good midrash, particularly in how it chooses to narrow in on a character from the book of Hosea (Gomer, played by the wonderful Camille Rowe) whom we know very little about, giving her both context and agency. This context and this agency feels especially important for a book that begins with a verse like this:

“When the Lord first spoke through Hosea, the Lord said to Hosea, ‘Go, take to yourself a wife of whoredom and have children of whoredom, for the land commits great whoredom by forsaking the Lord.'”

—Hosea 1:2,3

The story of Gomer, which is immediately swept up into the harshness of this language before disappearing into the shadows of the oracles to follow, gets even more complicated when considering her in light of chapters 1-3, which forms the first part of the book of Hosea (the second being the oracles). The best way to gain a sense of what the director is doing with this adaptation, especially in how it desires to explore the themes of the book from a woman’s perspective, is to look closely at the text itself.

The Book of Hosea

“When Israel was a child, I loved (her).”

—Hosea 11:1

An important part of the discussion when it comes to the demonstrable relationship between Hosea and Gomer is understanding how this relationship is used to symbolize the relationship between Yahweh and Israel. The context for Hosea is a period of time (mid 700’s BCE to early 600) leading up to the eventual exile of Israel. What we know of Israel and their kings during this time is that they were a bit of a mess when it came to their relationship with God, and the imagery it uses to help us understand the relationship between Israel and Yahweh is that of an unfaithful marriage: Yahweh as the husband and Israel as the adulterous wife who have given themselves to the worship of Baal.

An important part of the discussion when it comes to the demonstrable relationship between Hosea and Gomer is understanding how this relationship is used to symbolize the relationship between Yahweh and Israel. The context for Hosea is a period of time (mid 700’s BCE to early 600) leading up to the eventual exile of Israel. What we know of Israel and their kings during this time is that they were a bit of a mess when it came to their relationship with God, and the imagery it uses to help us understand the relationship between Israel and Yahweh is that of an unfaithful marriage: Yahweh as the husband and Israel as the adulterous wife who have given themselves to the worship of Baal.

Thematically speaking, the Book of Hosea is ultimately about the far reaching love of Yahweh into the dark places of our lives, a love that is capable of reshaping how we see Yahweh’s relationship to us in light of a broken covenant on the part of Israel. In an interview about the film, Dobson suggests that what he was really interested in was exploring this idea of commodified relationships that seems to be present in the text. Gomer’s lack of visible agency in the book of Hosea gets translated to a similar relationship with the men in the film, and we essentially see her being traded back and forth like property. The director then wondered about what it would look like to see this experience through Cate’s (Gomer’s) eyes. Dobson uses this experience to allow the dominant message of God’s love to then afford her a degree of agency as we watch her having to deal with the reality of feeling like a commodity. Both the Book of Hosea and this film essentially reveal God’s radical love breaking through the noise of the negative cultural assumptions of Gomer’s day, and likewise in Cate’s modern day context. The director also speaks in the interview about the intention behind setting it in Oklahoma, the Bible belt of America. What Gomer would have faced in the ancient setting felt like it had much to say about what Cate would have faced living in the heart of the Bible belt.

As we dig further into the text of Hosea chapter 1, following the call of Hosea to go and “take” a wife from a people who have been exhibiting adulterous behavior, we get the story of the birth of Hosea and Gomer’s 3 children. What’s interesting about the three names of the children is that they are named “punishment,” “no mercy,” and “not my people,” three names that symbolize the reality of a broken covenant in which God has promised to save (or deliver), to have mercy, and to call them His people. We then come to 1:10 where we find a picture of covenant renewal. In the light of these 3 children, “yet,” it says, the number of the children of Israel will be too numerous to measure, like the sands of the sea; and, in one of the most powerful statements in the book (and one the filmmaker pulls out of the text in a unique way), “in the place where it was said to them ‘you are not my people,’ it shall be said to them that they are “children” of the living God.”

As we dig further into the text of Hosea chapter 1, following the call of Hosea to go and “take” a wife from a people who have been exhibiting adulterous behavior, we get the story of the birth of Hosea and Gomer’s 3 children. What’s interesting about the three names of the children is that they are named “punishment,” “no mercy,” and “not my people,” three names that symbolize the reality of a broken covenant in which God has promised to save (or deliver), to have mercy, and to call them His people. We then come to 1:10 where we find a picture of covenant renewal. In the light of these 3 children, “yet,” it says, the number of the children of Israel will be too numerous to measure, like the sands of the sea; and, in one of the most powerful statements in the book (and one the filmmaker pulls out of the text in a unique way), “in the place where it was said to them ‘you are not my people,’ it shall be said to them that they are “children” of the living God.”

This promise forms the two halves of Hosea chapter 2 where we see the unfaithfulness of Israel contrasted with the merciful love of Yahweh. The punishment in these verses becomes a purifying act where their suffering and their unfaithfulness can be seen as a “door of hope.” “In that day,” Yahweh says, “you will call me ‘my husband’ and no longer will you call me ‘my Baal.’” God will “betroth” them to Himself forever, purifying them by uprooting the violence and oppression from their lives and freeing them to see and experience God’s love. As Baal promises fertility of land and body through the elements, God will “sow her for myself in the land, And I will have mercy on No Mercy, and I will say to Not My People, you are my people, and he shall say, “You are my God.” This will be the real fruit of Yahweh’s unending love. Here these two opposing messages come to a head, with God’s declaration of His Covenant faithfulness holding power over Israel’s unfaithfulness—and as with Gomer, the promise is not merely for her: it also applies to the generations to come.

This promise forms the two halves of Hosea chapter 2 where we see the unfaithfulness of Israel contrasted with the merciful love of Yahweh. The punishment in these verses becomes a purifying act where their suffering and their unfaithfulness can be seen as a “door of hope.” “In that day,” Yahweh says, “you will call me ‘my husband’ and no longer will you call me ‘my Baal.’” God will “betroth” them to Himself forever, purifying them by uprooting the violence and oppression from their lives and freeing them to see and experience God’s love. As Baal promises fertility of land and body through the elements, God will “sow her for myself in the land, And I will have mercy on No Mercy, and I will say to Not My People, you are my people, and he shall say, “You are my God.” This will be the real fruit of Yahweh’s unending love. Here these two opposing messages come to a head, with God’s declaration of His Covenant faithfulness holding power over Israel’s unfaithfulness—and as with Gomer, the promise is not merely for her: it also applies to the generations to come.

Hosea, who has seemingly distanced himself from Gomer at this point, is told by God to “go again” and to “love a woman who is loved by another man and is an adulteress, even as the Lord loves the children of Israel, though they turn to other gods and love cakes of raisins.” This becomes the template through which to see this relationship between Yahweh and Israel in the rest of the book. The symbolism of the Hosea-Gomer relationship tells us of the kind of relationship Yahweh has with Israel, and as the unfolding oracles in chapters 4-14 move from declarations of punishment to proclamations of acceptance, grace, mercy and love, and the symbol of this relationship begins to inform and give shape to the purifying process that calls Israel back to this covenant relationship with God.

Some scholars have argued about whether the woman in chapter 3 is Gomer or if it is a different woman altogether. This is because the woman in chapter 3 is not named, despite the majority view of the passage being reflected in the passage’s given descriptive: “Hosea Redeems His Wife.” I am with the majority here, as is the filmmaker, in seeing the two women as one and the same. Further, in seeing them as one and the same, chapter 3 actually allows this redemptive arc to make sense of the hard words of 1:2, where it would appear that God called Hosea to take an unfaithful woman as a wife and turn her into a commodity for the purpose of this redemption. This is actually a bit of a misleading translation of the word, as the word used is better understood to simply mean a woman from Israel who is living amongst the people of the land and participating in the practices and traditions of Baal worship. Although it could, this doesn’t necessarily mean this was someone who was sleeping around with multiple persons, which in the Patriarchal society of Gomer’s day would have been seen as acceptable for the male but not for the woman, even in the case of Israel. This is important to keep in mind when wrestling with the language of the text: the greater emphasis of this word is not on Gomer’s shame and action, but on God’s faithfulness in instituting and upholding the marriage between Yahweh and Israel. The command for Hosea is to return to a marriage relationship would have been considered shameful to those in his day, and to allow the love of Yahweh to inform who she truly is as a child of God. As a symbol of Israel, Gomer’s marriage to an oppressive culture and her adopting an identity that is not her own has left her oppressed and in a less than ideal situation. This was not what God desired for her, nor was it what God desired for Israel.

Some scholars have argued about whether the woman in chapter 3 is Gomer or if it is a different woman altogether. This is because the woman in chapter 3 is not named, despite the majority view of the passage being reflected in the passage’s given descriptive: “Hosea Redeems His Wife.” I am with the majority here, as is the filmmaker, in seeing the two women as one and the same. Further, in seeing them as one and the same, chapter 3 actually allows this redemptive arc to make sense of the hard words of 1:2, where it would appear that God called Hosea to take an unfaithful woman as a wife and turn her into a commodity for the purpose of this redemption. This is actually a bit of a misleading translation of the word, as the word used is better understood to simply mean a woman from Israel who is living amongst the people of the land and participating in the practices and traditions of Baal worship. Although it could, this doesn’t necessarily mean this was someone who was sleeping around with multiple persons, which in the Patriarchal society of Gomer’s day would have been seen as acceptable for the male but not for the woman, even in the case of Israel. This is important to keep in mind when wrestling with the language of the text: the greater emphasis of this word is not on Gomer’s shame and action, but on God’s faithfulness in instituting and upholding the marriage between Yahweh and Israel. The command for Hosea is to return to a marriage relationship would have been considered shameful to those in his day, and to allow the love of Yahweh to inform who she truly is as a child of God. As a symbol of Israel, Gomer’s marriage to an oppressive culture and her adopting an identity that is not her own has left her oppressed and in a less than ideal situation. This was not what God desired for her, nor was it what God desired for Israel.

Finding Gomer in the Book of Hosea

“In you the orphan finds mercy.”

—Hosea 14:3

In light of this reading of the larger story, what I find exceptional about the ways in which the filmmakers rescue Gomer from the silence of the text, giving her a voice and endowing her with agency, is that it gives us the freedom as modern readers to understand and consider the challenges Gomer would have faced in a strongly patriarchal society. It allows us to wonder about and consider how she might have felt, what she might have been thinking, and what kind of challenges she might have been carrying into this relationship with Hosea. This also then gives us the freedom to consider the ways in which the text can confront similar challenges in our own day, particularly when it comes to making sense of the God-Human relationship as a woman and from the perspective of being a woman in today’s world.

In light of this reading of the larger story, what I find exceptional about the ways in which the filmmakers rescue Gomer from the silence of the text, giving her a voice and endowing her with agency, is that it gives us the freedom as modern readers to understand and consider the challenges Gomer would have faced in a strongly patriarchal society. It allows us to wonder about and consider how she might have felt, what she might have been thinking, and what kind of challenges she might have been carrying into this relationship with Hosea. This also then gives us the freedom to consider the ways in which the text can confront similar challenges in our own day, particularly when it comes to making sense of the God-Human relationship as a woman and from the perspective of being a woman in today’s world.

This perhaps becomes most important when you consider this in light of Hosea 2. God is described as “stripping” Israel naked and making her like the “parched land” while “killing her with thirst.” If Gomer is treated as little more than a commodity in this text, to read these verses as a woman could very easily lead to feelings of shame and further acceptance of abuse. These are actions that we don’t see the character of Hosea do explicitly as a working symbol of Yahweh in relationship with Israel, but it is worth acknowledging that to approach this text as a woman represents specific challenges and obstacles in terms of understanding the character of God and God’s relationship to us. What the filmmakers can teach us here, I think, is that when we come to scripture, contextualization and recontextualization are equally important for seeing the larger picture, something that art, and more precisely in this case, film, can help us engage with on a deeper and more fundamental level. That is, we have to understand not only what the text means, but how the original audience would have heard it.

In terms of the Hosea text, this is where it becomes possible to begin to see that God was in fact working to reorient the dominant perspective of their day, including the shame that Gomer would likely have carried into this relationship with Hosea. To consider Gomer’s story from this perspective is to discover a woman now being freed from the oppressive systems that would have told her she was less than based on who they perceived her to be, even, one could say, for simply being a woman. As the message of Hosea unfolds, it becomes clear that this picture of Gomer is very different from who Yahweh sees her to be.

The director, a committed Christian with a seminary degree, uses the symbolism of the Hosea-Gomer relationship (contextualizing the text) to recontextualize the story using modern language and setting. The film is essentially asking, what does the Hosea story have to say to us today. By finding Gomer’s story hidden in the background of the text and giving it a voice, the film provides a context for understanding how she ends up where she is. The script layers her story with some necessary nuance, giving us a way to understand the problems of chapter 1 from the redemptive vantage point of chapter 3. For example, the opening scene of the film sees her quietly passing by her house as we hear her parents fighting in the background. We never see her parents, but because her parents are preoccupied this leads to them asking another man to pick her up from school and bring her home. These scenes provide us with an idea of why she ends up where she does when the film suddenly jumps to years later. In the absence of a clear model for what love is, Cate finds love in its less than ideal forms.

The director, a committed Christian with a seminary degree, uses the symbolism of the Hosea-Gomer relationship (contextualizing the text) to recontextualize the story using modern language and setting. The film is essentially asking, what does the Hosea story have to say to us today. By finding Gomer’s story hidden in the background of the text and giving it a voice, the film provides a context for understanding how she ends up where she is. The script layers her story with some necessary nuance, giving us a way to understand the problems of chapter 1 from the redemptive vantage point of chapter 3. For example, the opening scene of the film sees her quietly passing by her house as we hear her parents fighting in the background. We never see her parents, but because her parents are preoccupied this leads to them asking another man to pick her up from school and bring her home. These scenes provide us with an idea of why she ends up where she does when the film suddenly jumps to years later. In the absence of a clear model for what love is, Cate finds love in its less than ideal forms.

Given the symbolism of the text, the film also tells its own story in a very visual way. The concept of idols as a working image that appears throughout the story is woven into the fabric of the narrative in an inventive way. Of relevance to the story of Gomer are these different depictions of saintly women that emerge as icons, anchoring the importance of the woman’s perspective as one that situates Cate in the company of the strong women who have preceded her. Here she finds a model of strength and love in her own image as a child and servant of God. There is one scene in particular where, rather than positioning Henry (Hosea, played by Aiden Singh) as her savior, we see her being comforted and lifted up by another, older woman with the camera capturing the light breaking through and illuminating this picture of a cross in iconic form. These kinds of visuals help to give Gomer’s story a further sense of liberation. While Henry does model a different kind of love for Cate, he is never given agency over her. In fact, early on we come to understand that Henry’s parents are also likely getting a divorce. The film takes time to accent the problem of Henry’s long absence from Cate’s life. He is a realtor looking to convert a Church into a restaurant or apartments, which is why he is back in town (although we are given a sense there is a greater reason that drew him back), and we also come to learn that one of his associates is not the most upstanding of characters, something that gets in the way of the relationship between the two. Henry is presented as a flawed individual who demonstrates that the love Cate needs is a love that comes from outside of their relationship. This is a love that is able to inform them equally from their different vantage points in life as they deal with their differing experiences in relationship together.

Given the symbolism of the text, the film also tells its own story in a very visual way. The concept of idols as a working image that appears throughout the story is woven into the fabric of the narrative in an inventive way. Of relevance to the story of Gomer are these different depictions of saintly women that emerge as icons, anchoring the importance of the woman’s perspective as one that situates Cate in the company of the strong women who have preceded her. Here she finds a model of strength and love in her own image as a child and servant of God. There is one scene in particular where, rather than positioning Henry (Hosea, played by Aiden Singh) as her savior, we see her being comforted and lifted up by another, older woman with the camera capturing the light breaking through and illuminating this picture of a cross in iconic form. These kinds of visuals help to give Gomer’s story a further sense of liberation. While Henry does model a different kind of love for Cate, he is never given agency over her. In fact, early on we come to understand that Henry’s parents are also likely getting a divorce. The film takes time to accent the problem of Henry’s long absence from Cate’s life. He is a realtor looking to convert a Church into a restaurant or apartments, which is why he is back in town (although we are given a sense there is a greater reason that drew him back), and we also come to learn that one of his associates is not the most upstanding of characters, something that gets in the way of the relationship between the two. Henry is presented as a flawed individual who demonstrates that the love Cate needs is a love that comes from outside of their relationship. This is a love that is able to inform them equally from their different vantage points in life as they deal with their differing experiences in relationship together.

The other strong visual component in this film is the use of light and color. We see this in the use of candles and the use of reds to evoke certain emotions and meanings. We also see this in the way the film plays around with the idea of the “image,” similar to the way it uses the idols. Early on we see that one of Cate’s most cherished possessions is a camera. Rescued from the trash, she uses it to capture the faces and experiences around her. This artistic expression forms a subplot in the film that becomes a way for her to begin to use, develop and capture her voice. This creative process is intimately tied to the way the camera uses light and dark to capture different images, and these images play a role in telling her story as she navigates a problematic world and her attachment and bondage to it. These images help her to understand and see herself as she is, broken and raw but also as someone who is good, someone who is worthy of being loved and able to love in return. As viewers we can see her journey unfold from one who has been defined by the world around her to one who then finds her identity in God and God alone. This is a journey that the director affords her character through the reimagining of this recontextualized narrative, one that is arrives full of compassion, strength, humility, and grace, not simply for Israel, and not simply for humanity, but in light of the specific challenges that they face in a difficult world, also for all the women who desperately need to hear this same message—I am good, I am loved. Shame does not define me. I am not a commodity. I am not lesser. I am a child of God.

The other strong visual component in this film is the use of light and color. We see this in the use of candles and the use of reds to evoke certain emotions and meanings. We also see this in the way the film plays around with the idea of the “image,” similar to the way it uses the idols. Early on we see that one of Cate’s most cherished possessions is a camera. Rescued from the trash, she uses it to capture the faces and experiences around her. This artistic expression forms a subplot in the film that becomes a way for her to begin to use, develop and capture her voice. This creative process is intimately tied to the way the camera uses light and dark to capture different images, and these images play a role in telling her story as she navigates a problematic world and her attachment and bondage to it. These images help her to understand and see herself as she is, broken and raw but also as someone who is good, someone who is worthy of being loved and able to love in return. As viewers we can see her journey unfold from one who has been defined by the world around her to one who then finds her identity in God and God alone. This is a journey that the director affords her character through the reimagining of this recontextualized narrative, one that is arrives full of compassion, strength, humility, and grace, not simply for Israel, and not simply for humanity, but in light of the specific challenges that they face in a difficult world, also for all the women who desperately need to hear this same message—I am good, I am loved. Shame does not define me. I am not a commodity. I am not lesser. I am a child of God.

As faith-based films go this is the real deal. It’s a lower budget, indie passion project that I think proves its own worth simply as a legitimately good and well produced film. That it happens to bring such astute awareness to the text and profound insight into the God-Human relationship at the same time is what makes Hosea that much more special.

“Yet it was I who taught Ephraim to walk. I took them up by their arms, but they did not know that I healed them. I led them cords of kindness, with the bands of love, and I became to them as one who eases the yoke on their jaws, and I bent down to them and fed them.”

—Hosea 11:3-4