Aliens Just Like Us: The Man Who Fell to Earth (1976) & Under the Skin (2013)

“Every village and small country place is full of people who’ve just come and settled there without any ties to bring them. The big houses have been sold, and the cottages have been converted and changed. And people just come – and all you know about them is what they say of themselves.”

—A Murder is Announced, Agatha Christie

Aliens have undergone a renaissance as of late. A year ago, the New York Times released previously concealed reports of former Navy pilots describing their encounters with flying phenomena, which, according to one of the airmen, “accelerated like nothing I’ve ever seen.” Two months ago, the Pentagon formally released three videos showing the radar reports of these encounters, thereby confirming the oddity of those beguiling testimonies. Belief in aliens over the past couple of decades has risen exponentially as well. Over 60%of young Americans now believe in intelligent extraterrestrial life, higher than the percentage of Americans who “believe in God as described in the Bible”. With the rapid advancement of technology, new governmental and private endeavors such as Space Force and Space X, and a pop culture renewal in the idea of once again exploring the cosmos, humanity seems ever prepped for a close encounter with a third kind.

Aliens have undergone a renaissance as of late. A year ago, the New York Times released previously concealed reports of former Navy pilots describing their encounters with flying phenomena, which, according to one of the airmen, “accelerated like nothing I’ve ever seen.” Two months ago, the Pentagon formally released three videos showing the radar reports of these encounters, thereby confirming the oddity of those beguiling testimonies. Belief in aliens over the past couple of decades has risen exponentially as well. Over 60%of young Americans now believe in intelligent extraterrestrial life, higher than the percentage of Americans who “believe in God as described in the Bible”. With the rapid advancement of technology, new governmental and private endeavors such as Space Force and Space X, and a pop culture renewal in the idea of once again exploring the cosmos, humanity seems ever prepped for a close encounter with a third kind.

Yet what if aliens are already here? What if they slipped by, unnoticed and unaccounted for, and live and move here and there unattended to? Aliens as neighbors, friends, shoppers, watchers, bosses, and one night stands. What if aliens are just like us?

Released in 1976, The Man Who Fell to Earth tells the story of an alien, played by David Bowie (in his first starring role), who crashes into Earth in search of a way to ship water back to his desert planet which is suffering from a draught. Bowie’s alien, whom we later find out is named Thomas Jerome Newton, co-opts the advanced technology of his home planet to create a technological superpower named World Enterprises Corporation, whose sole private intent is to build his own spaceship to take him and a plenteous supply of water back home to his family. While on a trip to New Mexico (where the film was also shot), Thomas falls in love with a drifting hotel maid named Mary-Lou (Candy Clark), who introduces the austere and formidable Newton to the pleasures of her small-town life: religion, alcohol, and sex. As Newton further adjusts to the normal customs and habits of Southwestern American life, he quickly becomes consumed with alcohol and television. His appetite grows and grows, causing rifts in his and Mary-Lou’s relationship, and causing him to become disillusioned with his work.

Meanwhile, a fledging, horndog professor named Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), tired and worn out from the constraints and political correctness of the university system, has switched careers and started working for Newton, where they slowly become friends and confidants. Bryce, after a surreal encounter with Newton’s unhuman capabilities by the lake, quickly discovers Newton’s real identity by secretly scanning him with an X-ray. Newton, realizing Bryce has learned his true form, unveils his true self to Mary-Lou, who then flees in terror.

Meanwhile, a fledging, horndog professor named Dr. Nathan Bryce (Rip Torn), tired and worn out from the constraints and political correctness of the university system, has switched careers and started working for Newton, where they slowly become friends and confidants. Bryce, after a surreal encounter with Newton’s unhuman capabilities by the lake, quickly discovers Newton’s real identity by secretly scanning him with an X-ray. Newton, realizing Bryce has learned his true form, unveils his true self to Mary-Lou, who then flees in terror.

Eventually, Newton completes his spaceship, but as he is preparing to board, he is taken hostage by the government and a rival tech company, who confine him in an extravagant apartment. While in captivity, he is encouraged to indulge his vices of drink and endless entertainment, his days consumed by lounging on a bed watching a giant television, with drinks brought in to him on golden platters by room servants. He is also subjected to various medical treatments, as doctors poke and prod around his frame, trying to go beyond the skin which makes him appear human. During an X-ray test, the contact lenses he wears to make himself appear to have human eyes become glued shut, concealing the skin which covers his alien self permanently to his frame.

Mary-Lou, now in old age, visits the ageless and intoxicated Newton in his hotel suite, and after a violent outburst while trying to make love, are estranged from one another. Newton escapes the hotel and tries to graft himself back into the place of power and prestige he had once in society, in hopes of fulfilling his purpose of seeing his family once again. He is ultimately unsuccessful, falling back into the vices which previously enslaved him.

It is difficult to describe TMWFTE in concise genre terms. It is a love story, a satire on authoritarian capitalism, a science-fiction drama, a political thriller, a domestic tragedy, and a surrealist, erotic cult film all jumbled up into one. Preceded by Walkabout (1971) and Don’t Look Now (1973), this film cemented Roeg as the commercial heir to the experimental cinema, as he became the mainstream Buñuel for the sensationalism of the 70s. Like most of Roeg’s films (it should be noted that Roeg was a successful Cameraman and Cinematographer before he switched to the Director’s chair), it is best read as image preceding text.

The camera becomes its own character, a languid, yet sometimes erratic observer of the idiosyncrasies of small glances, unnerving memories, mental breakdowns, and sensual landscapes. The film upends itself in musical numbers and crosscuts that refuse any form of identification, often feeling like a penned rebellion against any semblance of idée fixe or leitmotif. The soundtrack (which is, oddly enough, Bowie absent) encompasses 70s experimental electronica, Louis Armstrong, segments from Holst’s ‘The Planets’, bluegrass music, and church hymns. Like it’s indefinable star, it is as futuristic and discordant as Bowie himself. Yet despite all of the stylistic and genre-crossing plumage, I find the film to be, at its core, a drawn-out ode fashioned after a simple parable.

The camera becomes its own character, a languid, yet sometimes erratic observer of the idiosyncrasies of small glances, unnerving memories, mental breakdowns, and sensual landscapes. The film upends itself in musical numbers and crosscuts that refuse any form of identification, often feeling like a penned rebellion against any semblance of idée fixe or leitmotif. The soundtrack (which is, oddly enough, Bowie absent) encompasses 70s experimental electronica, Louis Armstrong, segments from Holst’s ‘The Planets’, bluegrass music, and church hymns. Like it’s indefinable star, it is as futuristic and discordant as Bowie himself. Yet despite all of the stylistic and genre-crossing plumage, I find the film to be, at its core, a drawn-out ode fashioned after a simple parable.

About a third into the film, Dr. Bryce comes across a book of art on a side table. Flipping open to it, he sees Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s ‘Landscape with the Fall of Icarus’, with Auden’s famous poem on the work, “Musée des Beaux-Arts”, beside it. It reads:

In Bruegel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

For all the disparate camera and sound work, Roeg patiently lets the audience read the poem in its entirety, effectively thumping the viewer over the head with special dramatic emphasis. There are, he is saying, moments where the camera must let us read, rather than see, the story. Newton’s tale is Icarus’ tale, quite literally in the title, and Roeg is Brueghel, sketching the scene and observers of his quiet, tragic fall.

Yet it is not enough to compare TMWFTE to Icarus only, but in watching the film one thinks of A Brave New World as well. Newton falls not due to pride, not vanity, not greed. Bowie’s Newton seems quite immune to all the earthly and venial sins, and his ethereal and angelic silver frame gives him the celibate distance as a dispassionate observer amongst people who can’t control their passions. What drowns Newton in Breughel’s “green water” is consumption. TV, sex, violence, drink. Pleasure becomes Newton’s drug, entertainment his religion, violence his daily office. “The strange thing about television is that it doesn’t tell you everything. It shows you everything…” Newton says. The encyclopedic nature of the screen, the never-ending array of life by force of electrons, drowns Newton in his own slough of despondency. Like a true addict, who both loves and hates the vice he’s enamored and enslaved to, he shouts out to a wall of televisions, “Get out of my mind! All of you!” yet he cannot look away.

Yet it is not enough to compare TMWFTE to Icarus only, but in watching the film one thinks of A Brave New World as well. Newton falls not due to pride, not vanity, not greed. Bowie’s Newton seems quite immune to all the earthly and venial sins, and his ethereal and angelic silver frame gives him the celibate distance as a dispassionate observer amongst people who can’t control their passions. What drowns Newton in Breughel’s “green water” is consumption. TV, sex, violence, drink. Pleasure becomes Newton’s drug, entertainment his religion, violence his daily office. “The strange thing about television is that it doesn’t tell you everything. It shows you everything…” Newton says. The encyclopedic nature of the screen, the never-ending array of life by force of electrons, drowns Newton in his own slough of despondency. Like a true addict, who both loves and hates the vice he’s enamored and enslaved to, he shouts out to a wall of televisions, “Get out of my mind! All of you!” yet he cannot look away.

His infatuation swells inside him, manifesting even the laws of earth against him. In ascending an elevator, he becomes sick, feverish. The wax from Newton’s wings has sealed him in an ennui cocoon. Gravity has become his millstone, a reminder of the reason why he came to earth in the first place, a duty that he has failed to do. Visions or memories from his home planet flitter in and out of his mind, recollections of the family he left behind, his wife and children stranded in a waterless land. In one striking scene, in particular, we see Newton’s family walking towards us is a series of dissolving and overlapping paintings of arid and lush landscapes. Like Brueghel, Roeg is painting the plight of his tragic hero on screen, the past he had, and the future he won’t.

Roeg seems to be asking: What do we do when we can’t go home again? This is the existential dread that consumes Newton, leading him to swallow himself in despair. He has passed the point of no return. There is no prodigal son, and even further, because of his choices and temptations his friends have thrust upon him, there is no home to go back to either. Like Icarus, Newton has fallen into his own pond of alcohol and entertainment, and like the ploughman, his friends have passively watched him drown.

Like TMWFTE, Glazer’s Under the Skin is equally as hard to pin down. Directed by Jonathan Glazer and released in 2014, Under the Skin tells the story of an extraterrestrial creature, described in the script as The Female (Scarlett Johansson) who disguises herself as a young woman, whose sole duty is to prey upon the lustful charms of the young men of Glasgow, Scotland, and seduce them back to her home where she drowns them in a mysterious black pool. Much of the film is shot with hidden cameras in a van, as we follow her around the town as she tries to portray herself as lost, confused, and desperately needing a man to give her directions.

Like TMWFTE, Glazer’s Under the Skin is equally as hard to pin down. Directed by Jonathan Glazer and released in 2014, Under the Skin tells the story of an extraterrestrial creature, described in the script as The Female (Scarlett Johansson) who disguises herself as a young woman, whose sole duty is to prey upon the lustful charms of the young men of Glasgow, Scotland, and seduce them back to her home where she drowns them in a mysterious black pool. Much of the film is shot with hidden cameras in a van, as we follow her around the town as she tries to portray herself as lost, confused, and desperately needing a man to give her directions.

She continues her nightly routine until she meets The Deformed Man (Adam Pearson), whose facial deformity and genteel niceness causes her to experience an awakening of grief or mercy, as she lets him go after she takes him home. Fearing for her life, and from punishment by a sort of alien tax collector known as The Bad Man (Jeremy McWilliams) who haunts the Scottish countryside by motorbike, she leaves the city. While hiding in a small town, a man offers her his home and takes her in. One night, after watching television together, they kiss and try to have sex, but she pulls back, then runs away. Wandering in a forest, she encounters a haggard-looking commercial logger (Dave Acton), who attempts to rape her. During the act, he tears part of her skin off, revealing a black, tar-like, expressionless form underneath. In fear, he douses her with fire and flees, leaving her burning in the falling snow.

Upon first viewing, it is easy to riddle oneself with questions. The film is minimalist by design, and the special emphasis on visual components leaves the audience ample room to sinew together Glazer’s alien, sex-salved, underworld. Is this a film of layered significance, or did I watch the equivalent of a small house mouse casting a large, imperious shadow on the wall; does its tone confirm or reveal a lack of symbolic significance? In the earlier parts of Glazer’s career, he directed music videos, which, to detriment or value is for the viewer to decide, is readily apparent in this work. The score at times seems to be the main character when none are on screen, or when the landscape around them seems to envelop them into insignificance. Composed by Mica Levi, the score sounds like a collaboration between Penderecki and Radiohead, a doldrum of repeating beats and synthesized smears under the peck and patter of frantic strings.

Perhaps what makes this film so hard to register is its disjointedness with the rest of recent cinema. This is very much a movie out of its time. It is closer to the religious surrealism of Jodorowsky than the hardened philosophizing of science fiction post Blade Runner. Glazer seems to be working in the same vein as Roeg himself. Both films put the image as subjective to other technical aspects of filmmaking: the editing, the sound mixing, and those electronic bee nests of scores. Even in the grandest of Glazer’s frames, where his cold formality can be mistaken for a still from a Kubrick film, the image is always secondary to what’s accompanying it. Watching this film is like listening to Schoenberg, even when the film is at its most structured, the discordance is precisely the point.

Perhaps what makes this film so hard to register is its disjointedness with the rest of recent cinema. This is very much a movie out of its time. It is closer to the religious surrealism of Jodorowsky than the hardened philosophizing of science fiction post Blade Runner. Glazer seems to be working in the same vein as Roeg himself. Both films put the image as subjective to other technical aspects of filmmaking: the editing, the sound mixing, and those electronic bee nests of scores. Even in the grandest of Glazer’s frames, where his cold formality can be mistaken for a still from a Kubrick film, the image is always secondary to what’s accompanying it. Watching this film is like listening to Schoenberg, even when the film is at its most structured, the discordance is precisely the point.

The film is remarkably open, holding nothing back in relation to the sexuality of its character, or the topic of its themes. In the scenes of seduction, we see men, multiples of them, get completely undressed before The Female. As she undresses, they follow suit, until she turns around and begins to walk backward, beckoning them forward into their doom. Glazer crafts for us a great parable of temptation. There is no bed in sight, no couch to make love on, no blanket to pull oneself close to. All around is a cold, bottomless void, but the impulse to indulge is always greater than the Hell that threatens to overtake you if you do. As she glides along the surface, her victims slowly entomb themselves underneath the abyss. Later on, we find out that, for a period at least, that those consumed by it are cognizant enough to know they are being broken down, and aware enough to see the surface from which they came from. This is Glazer’s own inferno, his own Rich Man and Lazarus. But, unlike the Rich Man, they are silenced by their sins forever, forced to watch victim after victim make the same mistake as them, shut up from warning all who enter that their demise is certain and true.

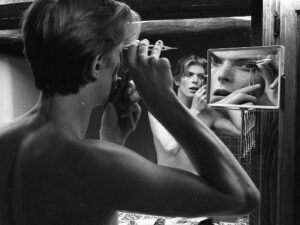

Yet for all its luridness, all its sexuality and lust that brims to the surface with each man she entices, the film also feels remarkably chaste. Johansson, arguably the most glamourous and sexualized actress working today, is revealed to us, as, well, one of us. An actress that has been for the majority of her career thrust into air-vacuumed tights and paraded and positioned on screen as the 21st century’s pin-up bombshell, is stripped bare, and in effect, stripped of that sensuality as well. The camera does not slip slowly up her legs, or settle on her hips, or ogle at her breasts. But rather, like Johansson’s alien herself, stares at her as though through a display glass: observant, scientific, and even with a tinge of melancholy. We see The Female turnabout slowly in the mirror under dim and egregious closet lighting, cautious, inquisitive, and even a little bit embarrassed. Glazer knowingly uses Johansson’s stardom against us and slaps us with the condemnation of the sexualization that we place upon her. She, too, has skin that sags. Even aliens look in the mirror.

Yet for all its luridness, all its sexuality and lust that brims to the surface with each man she entices, the film also feels remarkably chaste. Johansson, arguably the most glamourous and sexualized actress working today, is revealed to us, as, well, one of us. An actress that has been for the majority of her career thrust into air-vacuumed tights and paraded and positioned on screen as the 21st century’s pin-up bombshell, is stripped bare, and in effect, stripped of that sensuality as well. The camera does not slip slowly up her legs, or settle on her hips, or ogle at her breasts. But rather, like Johansson’s alien herself, stares at her as though through a display glass: observant, scientific, and even with a tinge of melancholy. We see The Female turnabout slowly in the mirror under dim and egregious closet lighting, cautious, inquisitive, and even a little bit embarrassed. Glazer knowingly uses Johansson’s stardom against us and slaps us with the condemnation of the sexualization that we place upon her. She, too, has skin that sags. Even aliens look in the mirror.

In retrospect of the #MeToo movement, the film feels like a searing diatribe against the culture which brought the movement about. Men are only willing to believe in the distress of women when they can also see a way to benefit from that very distress. Eagerness and prideful presumption become their sin. Charity for the men she picks up is merely a pawn to get the thing they really desire: her. Yet at the same time, the method she uses to punish those is the same impulse that leads the men astray. She consumes the consumers.

We are never permitted the specifics of her task. Is she feeding something? Is this black pool an extension of her, a life force? Is she fulfilling a quota, or paying off a debt to an alien Sheol? Our only clue comes from the beginning of the film when The Bad Man provides her a body from whom to take clothes from. Perhaps this girl too was like her, seducing and leading astray, feeding, or fulfilling some alien purpose. Perhaps she, too, discovered that in constantly consuming she was only consuming herself, but found out, just like The Female, that their kind is immune to the word grace.

We are never permitted the specifics of her task. Is she feeding something? Is this black pool an extension of her, a life force? Is she fulfilling a quota, or paying off a debt to an alien Sheol? Our only clue comes from the beginning of the film when The Bad Man provides her a body from whom to take clothes from. Perhaps this girl too was like her, seducing and leading astray, feeding, or fulfilling some alien purpose. Perhaps she, too, discovered that in constantly consuming she was only consuming herself, but found out, just like The Female, that their kind is immune to the word grace.

After she flees from her habitual trapping of luring the young men of Glasgow, she stops by a small diner and orders herself a large piece of chocolate cake. Upon taking a bite, she spits it out. Whether by her own choices or by those thrust upon her, even the mercies of life have been closed off to her. She tries to love a man in the small village where she finds safety, but upon nearing the climax of their passion, she pulls away, unable to separate the nakedness of love with the nakedness which led her to consume others. Perhaps it was grace, perhaps he too would’ve been consumed, drowned in another cold, black abyss. Maybe she’s a scarlet-lettered Jezebel, doomed to her own seductions, caught in an otherworldly pact that bars her off to the rest of humanity. But, perhaps, by force of those around her, both alien and human, both supernatural and those of Earth, she has become so hollowed out that to go beyond the wheel of devouring is impossible. She has become built for consumption, an empty machine that can do nothing but kill.

TMWFTE and Under the Skin both ask: why would we believe aliens would be any different from us, anyway? The allures of life are too trapping, the snares we place on ourselves too wide, and the guilt within us too deep. In the end, by our own choices or by those thrust upon us, we all become our own ouroboros, trapped in a cycle of endless consumption. Will they, too, not be swallowed by doubt or self-loathing? Can an alien escape the perils of being human? Or will they not also get caught in the web of substances, sensuality, and despair? Perhaps they too, will stand in front of the mirror, naked and alone, wondering, “Is this who I really am?” They will never be any stranger to us than we are already to ourselves.

TMWFTE and Under the Skin both ask: why would we believe aliens would be any different from us, anyway? The allures of life are too trapping, the snares we place on ourselves too wide, and the guilt within us too deep. In the end, by our own choices or by those thrust upon us, we all become our own ouroboros, trapped in a cycle of endless consumption. Will they, too, not be swallowed by doubt or self-loathing? Can an alien escape the perils of being human? Or will they not also get caught in the web of substances, sensuality, and despair? Perhaps they too, will stand in front of the mirror, naked and alone, wondering, “Is this who I really am?” They will never be any stranger to us than we are already to ourselves.

At the end of the TMWFTE, we see Dr. Bryce, now in his elder years, enter into a record store before going to meet Newton for lunch and purchase an album entitled ‘The Visitor’, which we later find out Newton had recorded (Like Bowie’s actual soundtrack for the film, we don’t get to hear anything from this album, either). “[I made it] for my wife. She’ll get to hear it one day. On the radio.” a day-drunk Newton says to Bryce, sitting outside a rooftop café with another nearly finished drink in hand. “I may not stay sober anymore, but I still have money.” Newton drops his drink. A waiter nearby rushes over to grab his glass. “I think maybe Mr. Newton has had enough, don’t you?” Bryce replies, “I think maybe he has.”

Thomas Zak is a film worker and writer living in Baton Rouge, LA. He has had poems published in DigBR, Wonder South, and Fathom Magazine.