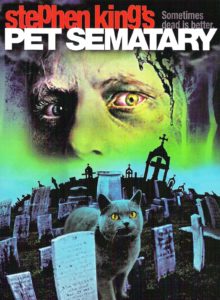

A Theological Conversation with Pet Sematary (1989)

Stephen King admits that Pet Sematary may be the most frightening work he’s ever written. Maybe that’s why it’s so complex theologically; both the 1989 film and the 1983 book upon which it is based have lots to say about theology and place, idols, icons, iconoclasm, and (of course) resurrection. The conversation we can have with King’s most frightening work takes us past the deadfall; let’s talk to some undead cats.

Stephen King admits that Pet Sematary may be the most frightening work he’s ever written. Maybe that’s why it’s so complex theologically; both the 1989 film and the 1983 book upon which it is based have lots to say about theology and place, idols, icons, iconoclasm, and (of course) resurrection. The conversation we can have with King’s most frightening work takes us past the deadfall; let’s talk to some undead cats.

Theology of Place

Theologian Walter Brueggemann writes, “Place is space that has historical meanings, where some things have happened that are now remembered and that provide continuity and identity across generations.”1

Place is primary in Pet Sematary. No longer tied to people, the Micmac burying grounds act as a primary character. The place has the ability to transform and control what goes on underneath its surface. And its historical meaning is crucial to the narrative: residents of Ludlow claim that the land became sour during the end of the Indians’ time. The Micmac Indians buried their dead there. It’s not clear whether or not they expected their dead to rise.

The Wendigo is a demon spirit that roams the forest in the place surrounding the burial grounds. It is connected to the land and to the Indians’ mythology. The Wendigo is also tied to the land, threatening anyone who comes near the burying ground. Could it be that this place created a demon spirit, bringing the dead to life, and thus compelling the Indians to leave? This question is left unanswered and up for speculation.

Willie James Jennings writes in The Christian Imagination about the French and British armies during colonial times creating new systems and forming literary spaces in order to “[survey] the world, assessing its needs, potentials, and places for mission and pastoral intervention.” From this, “a different sense of time and space was regnant, one calibrated eschatologically. This was time and space not bound to the historical occurrences of people.”2

One can say that Jud has in some way surveyed Louis and his family, their needs, their potential, places for mission and his own pastoral intervention. When the cat dies, Jud with his pastoral instincts recognizes Louis’s potential and his need to appease his children. Thus he takes him to the Indian burying ground for the mission to resurrect the cat. The ground itself however is not bound to time, space, or people anymore. The place no longer identifies with specific people groups, it chooses its people. It chooses them based on who buries their dead there.

Iconoclasm: Image and Presence and Pet Sematary

Natalie Carnes writes, “What does Love look like on the other side of torture and death?”3 An apt question for Louis Creed. Carnes references Christ’s death on the cross and the love on the other side of his death. Louis saw the death and burial of his 2-year old son. Louis’s love for his son carried him to do the atrocious thing and bury him in the Indian burying ground expecting that he would be raised from the dead. Louis had an image in his head of a reborn Gage, of his son returning to him. He imagined that he may be a little different, but he would still be his son, and he would still love him regardless of his likely zombie status.

Gage coming back to life became an idol for Louis. Carnes says, “an idol, in contrast, not only claims presence; it circumscribes the divine presence it claims. Often idols are also spectacles, which are hyper-visible, claiming that there is nothing invisible left of the signified.”4 Louis clung to his idolization of Gage, and couldn’t see past his imagined perfection. In the course of events, when Gage does come back to life, he becomes the idol incarnate, albeit not in the way Louis imagined. He’s more like what Carnes describes. Gage is a spectacle—a demon possessed being. Assuming for the sake of analogy that real Gage pre-death is the divine, the idol that is created after his resurrection has circumvented his divinity and becomes instead demonic. Nothing remains of the actual Gage. Louis realizes this, that he has created this image and he must now break it. Carnes says, “the very urgency to break an image insinuates the existence of a power that needs to be denied.”5

Gage coming back to life became an idol for Louis. Carnes says, “an idol, in contrast, not only claims presence; it circumscribes the divine presence it claims. Often idols are also spectacles, which are hyper-visible, claiming that there is nothing invisible left of the signified.”4 Louis clung to his idolization of Gage, and couldn’t see past his imagined perfection. In the course of events, when Gage does come back to life, he becomes the idol incarnate, albeit not in the way Louis imagined. He’s more like what Carnes describes. Gage is a spectacle—a demon possessed being. Assuming for the sake of analogy that real Gage pre-death is the divine, the idol that is created after his resurrection has circumvented his divinity and becomes instead demonic. Nothing remains of the actual Gage. Louis realizes this, that he has created this image and he must now break it. Carnes says, “the very urgency to break an image insinuates the existence of a power that needs to be denied.”5

Resurrection

Toward the beginning of Pet Sematary, Ellie tells her father, “Let God have his own cat! Church is my cat!”6 Louis doesn’t believe in God, but Ellie has faith, even if she thinks God is going to take her cat away from her in its death. To Louis, dead is dead, there’s no coming back from it.

In John 11, Lazarus falls ill and dies. Jesus says to Martha, “Your brother will rise again.” But she says, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus then says to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die” (John 11:23-25). In this, Jesus says that only through relationship with him will anyone live forever. He also says this to show that he is the only one that gives life.

Throughout the book, Louis recollects the instance when Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. After Gage dies, Louis has a conversation with Ellie. She tells him, “I’m going to wish really hard…and pray to God for Gage to come back.”7 She relates the story of Lazarus that her teacher taught in school and adds, “probably everybody in that graveyard would have come out, [but] Jesus only wanted Lazarus.”8

Throughout the book, Louis recollects the instance when Jesus raised Lazarus from the dead. After Gage dies, Louis has a conversation with Ellie. She tells him, “I’m going to wish really hard…and pray to God for Gage to come back.”7 She relates the story of Lazarus that her teacher taught in school and adds, “probably everybody in that graveyard would have come out, [but] Jesus only wanted Lazarus.”8

Louis acts like Jesus, thinking that through the power of the Indian burying ground, he too can raise someone from the dead. However, it’s a sinister power that brings dead things to life. By using Lazarus as a metaphor, King shows that spirits have power, either through place or icons. These can call forth life. But only God can bring back true life.

“Sometimes dead is better.”9

• • •

Footnotes:

1 Walter Brueggemann. Land Revised Edition (Overtures to Biblical Theology) (Kindle Locations 336-337). Kindle Edition

2 Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. Yale University Press. (Kindle Location 4988). Kindle Edition

3 Carnes, Natalie. Image and Presence (Encountering Traditions) (pp. 123-124). Stanford University Press. Kindle Edition

4 Carnes, 124

5 Carnes, 95

6 King, Stephen. Pet Sematary. Scribner. Kindle Edition. Location 106.

7 King, 322

8 King, 322-323

9 Ibid.

A Theological Conversation with Pet Sematary (1989)

July 3, 2019Radha Vyas Commentary, Horror, Mystery, Thriller0

Theology of Place

Theologian Walter Brueggemann writes, “Place is space that has historical meanings, where some things have happened that are now remembered and that provide continuity and identity across generations.”1

Place is primary in Pet Sematary. No longer tied to people, the Micmac burying grounds act as a primary character. The place has the ability to transform and control what goes on underneath its surface. And its historical meaning is crucial to the narrative: residents of Ludlow claim that the land became sour during the end of the Indians’ time. The Micmac Indians buried their dead there. It’s not clear whether or not they expected their dead to rise.

The Wendigo is a demon spirit that roams the forest in the place surrounding the burial grounds. It is connected to the land and to the Indians’ mythology. The Wendigo is also tied to the land, threatening anyone who comes near the burying ground. Could it be that this place created a demon spirit, bringing the dead to life, and thus compelling the Indians to leave? This question is left unanswered and up for speculation.

Willie James Jennings writes in The Christian Imagination about the French and British armies during colonial times creating new systems and forming literary spaces in order to “[survey] the world, assessing its needs, potentials, and places for mission and pastoral intervention.” From this, “a different sense of time and space was regnant, one calibrated eschatologically. This was time and space not bound to the historical occurrences of people.”2

One can say that Jud has in some way surveyed Louis and his family, their needs, their potential, places for mission and his own pastoral intervention. When the cat dies, Jud with his pastoral instincts recognizes Louis’s potential and his need to appease his children. Thus he takes him to the Indian burying ground for the mission to resurrect the cat. The ground itself however is not bound to time, space, or people anymore. The place no longer identifies with specific people groups, it chooses its people. It chooses them based on who buries their dead there.

Iconoclasm: Image and Presence and Pet Sematary

Natalie Carnes writes, “What does Love look like on the other side of torture and death?”3 An apt question for Louis Creed. Carnes references Christ’s death on the cross and the love on the other side of his death. Louis saw the death and burial of his 2-year old son. Louis’s love for his son carried him to do the atrocious thing and bury him in the Indian burying ground expecting that he would be raised from the dead. Louis had an image in his head of a reborn Gage, of his son returning to him. He imagined that he may be a little different, but he would still be his son, and he would still love him regardless of his likely zombie status.

Resurrection

Toward the beginning of Pet Sematary, Ellie tells her father, “Let God have his own cat! Church is my cat!”6 Louis doesn’t believe in God, but Ellie has faith, even if she thinks God is going to take her cat away from her in its death. To Louis, dead is dead, there’s no coming back from it.

In John 11, Lazarus falls ill and dies. Jesus says to Martha, “Your brother will rise again.” But she says, “I know that he will rise again in the resurrection on the last day.” Jesus then says to her, “I am the resurrection and the life. Whoever believes in me, though he die, yet shall he live, and everyone who lives and believes in me shall never die” (John 11:23-25). In this, Jesus says that only through relationship with him will anyone live forever. He also says this to show that he is the only one that gives life.

Louis acts like Jesus, thinking that through the power of the Indian burying ground, he too can raise someone from the dead. However, it’s a sinister power that brings dead things to life. By using Lazarus as a metaphor, King shows that spirits have power, either through place or icons. These can call forth life. But only God can bring back true life.

“Sometimes dead is better.”9

• • •

Footnotes:

1 Walter Brueggemann. Land Revised Edition (Overtures to Biblical Theology) (Kindle Locations 336-337). Kindle Edition

2 Willie James Jennings, The Christian Imagination: Theology and the Origins of Race. Yale University Press. (Kindle Location 4988). Kindle Edition

3 Carnes, Natalie. Image and Presence (Encountering Traditions) (pp. 123-124). Stanford University Press. Kindle Edition

4 Carnes, 124

5 Carnes, 95

6 King, Stephen. Pet Sematary. Scribner. Kindle Edition. Location 106.

7 King, 322

8 King, 322-323

9 Ibid.

Written by Radha Vyas

Radha is a grad student at Dallas Theological Seminary with an emphasis in film, culture, and apologetics. She writes, photographs, and studies theology. You can find her on Instagram @firestripe.

Related Articles

S07 E06 – A Christmas Story and Magic in the Margins

December 27, 20190

S07 E05 – The Rise of Skywalker and Choosing Our Family

December 26, 20191

S07 E04 – A Beautiful Day in the Neighborhood and Seeing Humanity

December 16, 20192