7 Questions for Reed Lackey, Writer of 40: The Temptation of Christ

I watched Douglas James Vail’s 40: The Temptation of Christ, and I had some questions.

I watched Douglas James Vail’s 40: The Temptation of Christ, and I had some questions.

So I decided to ask the screenwriter.

Reed Lackey is a friend of Reel World Theology; he’s one half of Christian horror podcast The Fear of God, active on More than One Lesson, and has written for us on multiple occasions (he even wrote for me when Trektember was part of Redeeming Culture!). I was delighted that his recent feature film screenwriting credit hasn’t gone to his head, and he returned my email for this delightful interview. If you like this interview, make sure you click here to check out the companion podcast that Josh Crabb and I recorded about the film!

Enjoy!

• • •

David Atwell: I wanted to let you know that I just watched “40” tonight. I was impressed! It was a great achievement, and I really enjoyed it. Since I know you, and since Josh & I are about to record a podcast, I thought I would ask you a couple of quick questions about it. First, how did you come to write this script? And how did the final version of this film compare to your vision for it as you were writing it?

Reed: Doug (ed.: Douglas James Vail), the director, had been a friend of mine for some time and we’d worked on short projects together before, so he first brought the project to me. He called me in early 2017 and said he wanted to make a film about Christ’s time in the wilderness, but needed a writer and asked if I would be interested. The next day, I called him back and told him my idea for how to approach the story, which he—somewhat nervously—agreed to and then we were off and away. What you see in the finished film is extremely close to what we originally discussed in that initial conversation. The story itself matured as we developed it, but a large majority of the story we’d drafted—and the script I eventually wrote—made it to the screen.

David: What factors went into your decision to have Jesus speak entirely in Scripture? Did you struggle with choosing verses, or translations? Or with writing dialogue for other characters that felt like it fit in the same story?

David: What factors went into your decision to have Jesus speak entirely in Scripture? Did you struggle with choosing verses, or translations? Or with writing dialogue for other characters that felt like it fit in the same story?

Reed: The choice to make Jesus speak only scripture was a very early one. I wanted the freedom to explore the story’s many potential facets as creatively as possible and having Christ only speak in scripture provided an anchor which allowed me to take risks with the rest of the characters, particularly his parents. The choice of which specific scriptures to use, however, was a more challenging one. I chose to go with the NIV translation for its conversational accessibility, but I didn’t want to only use the most familiar passages. I knew I would be leaning heavily on the Psalms and the prophets, as well as some portions of what Jesus has said later in his ministry, but I wrote down more than fifty pages of potential passages to use in different contexts, only maybe 10-12 of which made it to the finished film. When constructing the scenes, the choice of scripture always had to be centered around the way we see Jesus use them against the enemy in the gospel account: to confront mysteries, questions, and challenges with “it is written…” That applied whether Jesus was trying to overcome fear or express gratitude or, of course, defeat temptation. It also provided an exercise to digest the scriptures in personal and creative ways I’d never tried before, which was difficult, but quite rewarding.

David: Part of that digesting had to be the Gospels. I love how you recontextualized Jesus’ entire life, prior and following, into the wilderness days. Was that the purpose at the outset, or did it emerge as you wrote?

David: Part of that digesting had to be the Gospels. I love how you recontextualized Jesus’ entire life, prior and following, into the wilderness days. Was that the purpose at the outset, or did it emerge as you wrote?

Reed: What we established from the very beginning—the concept behind our narrative approach—was that Lucifer would tempt Jesus using his family’s countenances. This drove me to try to think creatively about what elements of those relationships would make the temptations intensely difficult to resist. The enemy couldn’t just look like them, he needed to sound like them and lean on personal elements of their relationships to make his temptations compelling. This required some creative invention to sculpt who Mary and Joseph were as people and as parents, which ultimately yielded some of my favorite scenes.

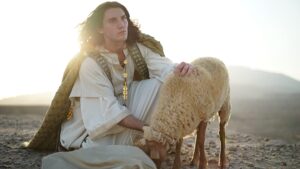

But Doug had also asked me a powerfully invaluable question early on that took a couple of months to solve in the script: “What is Christ doing while he’s out the wilderness, and what does He stand to lose?” I took lots of long walks just repeating that question to myself without much answer before I finally became captivated by Christ’s teaching on the Good Shepherd. I pictured this image — that did make it into the film — of Jesus stumbling upon a set of sheep’s tracks in the sand, but there’s another set of tracks following the sheep: the tracks of a predator. From that image, all of the elements surrounding the lamb grew into the script. It provided a structure for the journey of Christ as someone transitioning from the son of Mary and Joseph into the Good Shepherd who would lay down His life for the sheep. These elements then planted seeds for smaller and more intimate themes like Joseph and Jesus’s relationship or the suffering and death of innocence and the early visions of the cross to which He’s heading.

David: Was there ever a draft where Jesus picked the apple at the end, after having passed the test that Adam failed?

Reed: No, I knew before I ever started writing page one that I wanted the final moment to be Jesus looking at a fruit he wouldn’t take. But as obvious as that metaphor is, I also hoped for a moment which would celebrate the reconciliation of creation. Jesus doesn’t take the fruit, but he does find joy in its beauty, giving a window into the eventual hope of restoration at the heart of His coming. Everything’s back in its right place. I think Doug and Shayan — who played Jesus — captured that spirit beautifully in that moment.

David: On the other end of the spectrum, of course, is Lucifer. I’d love to hear about the decisions you made in writing Satan’s dialogue, and how you explored his motivations and mindset.

David: On the other end of the spectrum, of course, is Lucifer. I’d love to hear about the decisions you made in writing Satan’s dialogue, and how you explored his motivations and mindset.

Reed: Two main things drove how I approached writing for Lucifer: curiosity and choice. I pictured him being much more curious about Jesus than he was threatened by Him, at least at first. Essentially, a being of tremendous interest has come into his radar, someone who “smells” unique and yet strangely familiar. So he does what any bold being who is curious about a thing does: he explores it. He presses on it, asks it questions, tries to assess its strengths and weaknesses, and then—ultimately—tries to control it, which is a temptation terrifyingly common to all of us. This made Lucifer as a character immeasurably more interesting to me than the common, more maniacal approach of threats or scorn. He does show scorn, but usually only when he’s been made to look or feel foolish by failed efforts. And as for how I scripted his tactics within that curiosity, I did far more looking in the mirror than I was comfortable with to find what choices I frequently wrestle with in my own heart, like whether it is better to try to end suffering rather than learn from it, or be seen and known by others rather than to be faithful, or—worst of all—to talk myself into a private moment’s compromise for the “greater good”. I put those struggles into the hands of an intensely curious character and then turned him loose, which is what resulted in how Lucifer speaks and acts.

David: What one or two things that I didn’t mention do you want people to know about the film?

Reed: First, I have to mention that this project was intensely personal for both me and Doug in a multitude of ways, too many to list here. For Doug, it was a love letter of sorts, one he completely self-funded, produced, and directed. As for the script, there’s so much of my heart and spirit in it that it’s a little difficult to objectively analyze or assess how well it all works. But hopefully it works well for people and brings about a sense of hope and provokes thought, that was mainly what I wanted.

Second, I would love to mention a word or two about Joseph. The actor (Cazzey Louis Cereghino) brought a sense of earthiness to Joseph I’d never seen before. The character is often portrayed as a bit of a father-knows-best type and I love that Cazzey is a strong, but gentle man (the image of meekness). He ad-libbed his way through quite a few of his lines, capturing the essence but not quite the specific cadence I’d written, which gives him in the finished product a richer humanity than I could have originally pictured in my opinion. And it’s one of my favorite aspects of this particular version of this story that we wrestle a lot with his relationship to Jesus—and Jesus’s to him—in conversations about purpose and longing, or where he asks his son to remember him even though he knows he’s only a supporting player in this story. It’s that mystery of letting go, of surrendering to what you were gifted to participate in without demanding to be credited for it. And as Jesus himself wrestles with how to contextualize the place for Joseph in his heart, his last line is where he says, “This command was given to me…by my father.” We know which Father he’s referring to, but perhaps there’s a heartfelt echo of remembrance in that statement after all. (And yes, I intentionally pondered a “what if” that when the thief on the cross begs to be remembered, what if there were deeper echoes of remembrance that captured Christ’s heart in that moment. Probably not, but I love the thought of that.)

Second, I would love to mention a word or two about Joseph. The actor (Cazzey Louis Cereghino) brought a sense of earthiness to Joseph I’d never seen before. The character is often portrayed as a bit of a father-knows-best type and I love that Cazzey is a strong, but gentle man (the image of meekness). He ad-libbed his way through quite a few of his lines, capturing the essence but not quite the specific cadence I’d written, which gives him in the finished product a richer humanity than I could have originally pictured in my opinion. And it’s one of my favorite aspects of this particular version of this story that we wrestle a lot with his relationship to Jesus—and Jesus’s to him—in conversations about purpose and longing, or where he asks his son to remember him even though he knows he’s only a supporting player in this story. It’s that mystery of letting go, of surrendering to what you were gifted to participate in without demanding to be credited for it. And as Jesus himself wrestles with how to contextualize the place for Joseph in his heart, his last line is where he says, “This command was given to me…by my father.” We know which Father he’s referring to, but perhaps there’s a heartfelt echo of remembrance in that statement after all. (And yes, I intentionally pondered a “what if” that when the thief on the cross begs to be remembered, what if there were deeper echoes of remembrance that captured Christ’s heart in that moment. Probably not, but I love the thought of that.)

David: Finally, and this is very important: does the line “Satan disappears like Q in Star Trek” appear in the finished script?

Reed: Oh man….now I truly, truly wish it had said that! (Laughs)

David: Reed, thank you for your time and for answering our questions.

Reed: I have to tell you what a humbling thing it is to hear that anybody would even want to discuss our film, let alone record that discussion. How kind and generous of you to give me a chance to answer these questions; I’m very honored, man.

• • •

You can check out 40: The Temptation of Christ at Faithworks Pictures. You can also buy or rent it on Amazon Prime, Google Play, and iTunes.